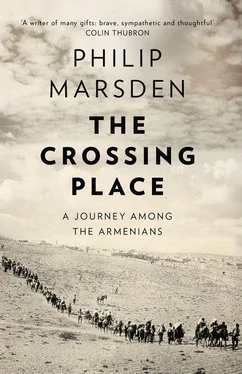

PHILIP MARSDEN

The Crossing Place

A Journey among the Armenians

Copyright Copyright About the Publisher

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers in 1993

Copyright © Philip Marsden 1993

Preface and postscript copyright © Philip Marsden 2015

Philip Marsden asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Cover photograph: Turkey / Armenia: Armenian refugees fleeing

Turkish massacres, Anatolia, 1915 © Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008127435

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780007397778

Version: 2015-03-17

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

The wind is singing, the leaves of the mulberry-tree are shuffling.

Eternal song; eternal life; eternal death; eternal sorrow; and eternal joy…

Vahan Totovents, Scenes from an Armenian Childhood ,

(Trans. Mischa Kudian)

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

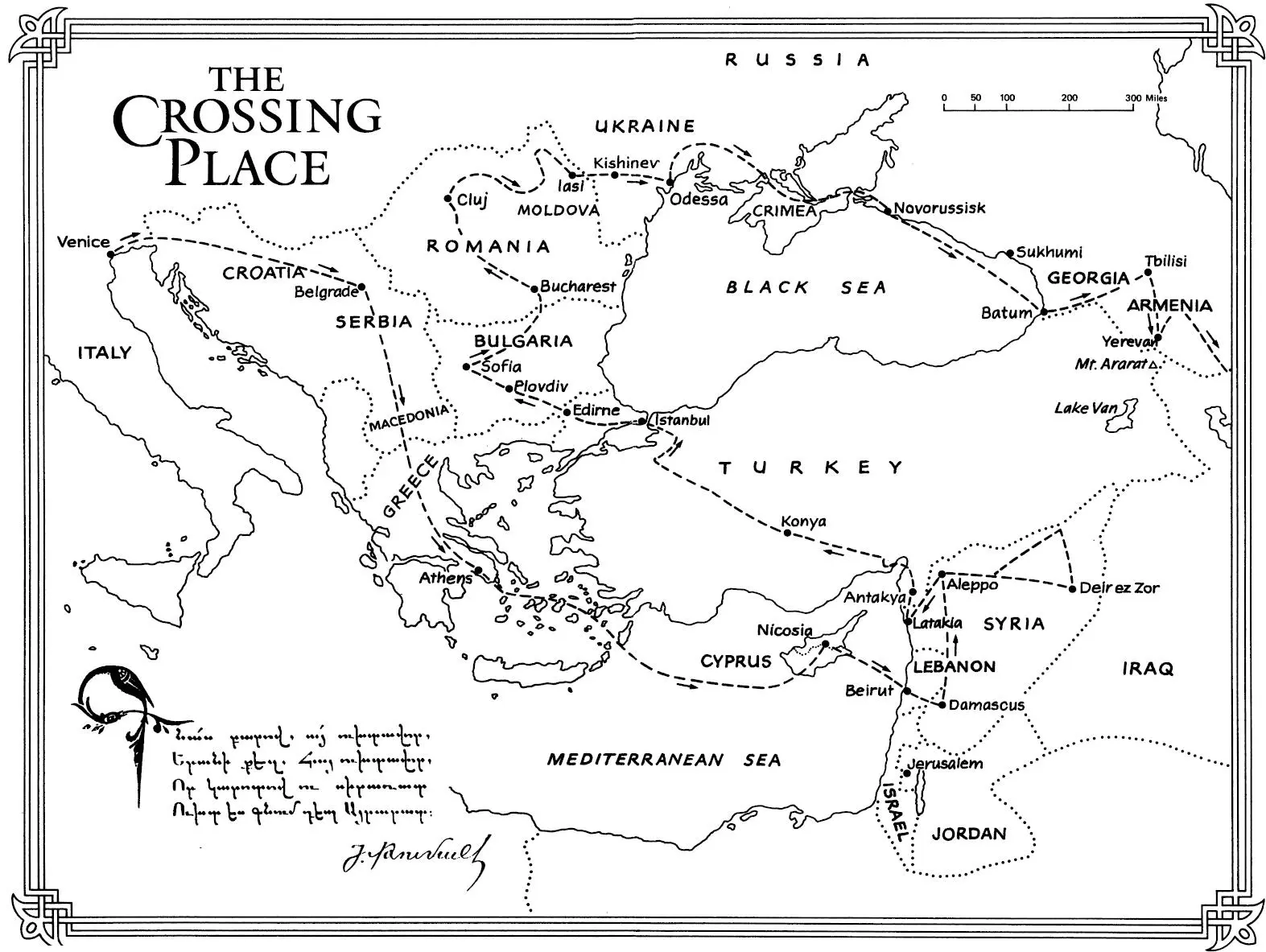

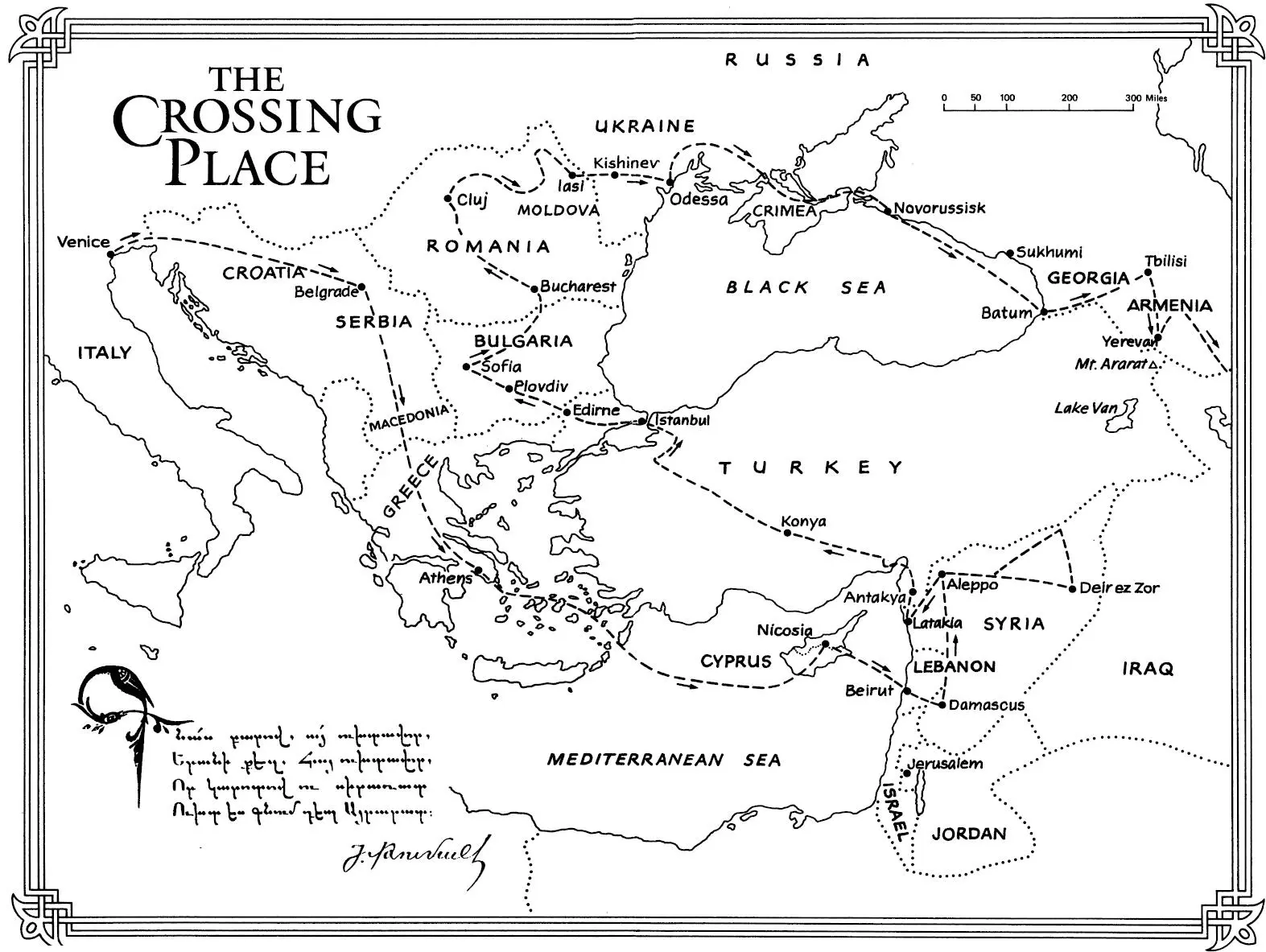

Map

Preface to the 2015 Edition

Prelude

Part I The Near East

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Part II Eastern Europe

9

10

11

12

13

14

Part III Armenia

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Postscript

Keep Reading

References

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

On a cold grey morning in January 1991 I stood beneath the departures board at London’s Victoria Station, waiting to catch the boat-train to Paris. A rucksack leaned against my shins and a crowd of commuters – blank-faced and winter-wrapped – flowed past me. I was in my late twenties, and I was going to Armenia.

In my pocket I had a black oilskin notebook with a list of Armenian sites and contacts in places from Venice to Nicosia, Damascus to Sofia, Aleppo to Cluj, Istanbul to Bucharest. I had arranged them by country, and the last page was headed USSR – still in existence, just, with names in Odessa, Tbilisi and Yerevan. I was wearing new boots and a new coat. In my rucksack was a change of clothes, a towel, books, two maps (one ‘Turkey and Western Asia’, the other ‘ Osteuropa ’), a short-wave radio, a Nikon F3 camera, a lot of transparency film, a letter of introduction from the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem and $2,000 in cash. I also had two passports, one with Israeli stamps and one without. In neither of the passports was a single visa.

I felt neither prepared nor unprepared; the uncertainty of the journey was too great to be nervous. I had developed an idea of the traditional Armenian diaspora as a powerful and secretive network of communities spread across the Middle East and Eastern Europe. If I locked into that network, and was accepted, all would be fine. Visas would appear, borders would open before me. At least that was what I hoped: proving it was part of the point of the journey. My two main fears were being kidnapped in the Levant and being turned back, anywhere. I was determined not to fly.

From Paris my plan was to carry on by train to Venice, then to Athens, and by ferry to Cyprus. That was the easy part. From then on, I would need visas and luck and the help of my contacts. The first decision would be whether or not to go to Lebanon. The bombing phase of the First Gulf War was already underway; Western hostages were still being held in Beirut and the Bekaa Valley.

For months before, I’d been living in a single-room flat in the Armenian quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City. I took daily lessons in Armenian with the charming Father Anooshavan, who was alleged to speak thirty-six languages. I spent a great deal of time with the poet and historian George Hintlian, who acted as mentor to my planned odyssey. I talked to monks, scholars and seminarians. I met recent refugees from Karabagh, second-generation refugees from Iran, and third-generation refugees from Turkey. In 1915 the entire Armenian population had been driven from Anatolia; many were massacred there, on the edge of dusty towns; many more were driven down into the Syrian desert. Over a million died. In Jerusalem, there were a few very old survivors who, in darkened rooms, laid their stories before me.

At that time the Old City was more than usually tense. On to the first Palestinian Intifada were heaped the war-fears that had followed Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. I recall the cheek-sting of tear gas, the fear of walking in the alleys at night, of a stone to the head or a street stabbing. I recall the Al-Aqsa massacre of 8 October and watching an Israeli settler standing in the Ghawanima minaret, shooting down at Palestinians in the concourse of the mosque.

That morning at Victoria station, I carried a couple of other things with me, things I’d picked up in Jerusalem. One was a particular strain of anger that is unavoidable if you spend any time in the Middle East. I had arrived in Jerusalem with an outsider’s view of the Palestinian conflict. But as the months passed and I saw the reality of day-today life, I found myself with a visceral reaction to the Israeli occupation. A similar indignation, overlaying any attempt at neutrality, had grown to colour my Armenian studies. In 1915, under threat from enemies on all sides, the Turkish authorities had every right to be nervous of Armenian loyalties. But what they did to the Armenians overshadows any political context. This book is not an attempt to explain the events of 1915; it is the record of my own experience of travelling among the Armenians, at a particular moment in world history, at a particular moment in my own life. Re-reading it now, more than two decades on, I can see how partisan I’d become, and remember how natural that position felt.

The other piece of baggage was something that would grow sharper over the coming months, that would stay with me for years afterwards. It was the idea that violence and disorder were the way of the world, and that at that time in the early 1990s, with the Middle East in chaos and the Soviet Union fracturing, they were both on the rise. I was, I recall now, in that state of mind that sees everywhere the signs of imminent catastrophe.

Two months later I reached the Syrian town of Deir ez Zor. After days in the desert, visiting the massacre sites, I crossed the Euphrates on a bus. It was late afternoon and a dusty light hung heavy over the town, as if the sun had lost its vigour. Down a side alley, I knocked on a door and an Armenian let me in swiftly and locked it behind him.

Читать дальше