Browne could only do so much tutoring with Mark, whose mind was almost permanently elsewhere. Firstly he was writing up an account of his recent travels with a view to having it published under the title Through Five Turkish Provinces , an ambition that was to be realized the following year. At the same time he was involved in numerous journalistic activities, contributing several pieces, for example, to the Cambridge student magazine The Granta , edited by his old friend George Bowles. In No. 266, for instance, he not only provided the leader, an article on the Militia titled ‘A Sangrado Policy’, but also a skit called ‘The Granta War Trolley’, a cartoon entitled ‘Taste’, the dramatic criticism, and an illustrated limerick. In addition he drew a series of sketches caricaturing various aspects of some of the British newspapers. These included ‘The Pillory of Truth ’, ‘ The Times ’ Sphinx’, and ‘The Imperial Ecstasy of the Daily Mail ’.

In October he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley, ‘I am starting a newspaper named ‘The Snarl.’ I calculate the loss on three copies about £10. I think the venture is worth trying … it may possibly pay its expenses. I calculate on a certain sale, but at the same time I am paying somewhat for the contributions and also on the necessary advertisement, so please send me a cheque book. I shall not tell my mother I have one, or use it for any other purpose but that of paying contributors … If you think my father will write to stop me, do not tell him as the production is well worth trying & may make me a certain kind of reputation.’ 1 The Snarl , was co-edited by a Cambridge friend, Edmund Sandars, but appears to have been entirely written by Mark, who also designed and drew the cover. The magazine was subtitled An Occasional Journal for Splenetics , and was a vehicle for him to let off steam on a variety of subjects.

Say what you please – say ‘D—n!’ say ‘H-ll!’

Say ‘botheration!’ Say ‘You Tease!’

Say ‘Don’t!’ Say ‘Dreary me!’ Say ‘Well!’

Say what you please!

Say that the Transvaal’s made of cheese!

Call Chamberlain Ahitophel!

Say women ought to have degrees! –

Say printers might know how to spell!-

Say petits pois means little peas! –

So long as this line ends in l ,

Say what you please. 2

In the only two issues that were published, he railed against compulsory chapel, attacked the Cambridge Union for degenerating ‘hopelessly and finally into the recognized organ of the great conformist conscience’, described the degree of Master of Arts as being nothing more than ‘the triumph of mediocrity’, and criticized the dons for their ‘narrow-minded ignorance of the world’. In the barely concealed anger and snappish tone of its articles, The Snarl anticipated the modern-day journalism of writers like Will Self and Charlie Booker.

The Cambridge life that Mark was now thoroughly enjoying was rudely interrupted by a conflict which erupted at the outer reaches of the British Empire. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the British had acquired the colony of South Africa to which the government had then actively encouraged British settlers to emigrate. This was the cause of conflict with the original, Afrikaans-speaking, Dutch population, who were known as ‘Boers’, many of whom migrated northwards, on ‘The Great Trek’, where they established two independent Boer republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, both of which were eventually recognized by the British. However, the discovery in the second half of the century of, first of all, diamonds at Kimberley, on the borders of the Orange Free State, and then of vast gold deposits in the Transvaal brought a massive influx of foreigners, ‘uitlanders’, mainly from Britain, who were needed to develop these resources. This caused increasing tensions with the Boers, who began to fear that they would soon become a minority in their own country. In 1899 their worst fears were realized when the British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, demanded full voting rights and representation for all uitlanders living in the Transvaal. It was over this that Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic, declared war on Britain in October 1899.

Having spent much of his childhood playing war games in the park at Sledmere, reading books on the great generals, and studying Vauban’s theories of fortification in the Library, it is not surprising that Mark had an affinity with the military. His heroes were Marshal Saxe, Marshal of France in the reign of Louis XV, and the Emperor Napoleon, as whom he had a penchant for occasionally dressing up.

In his first year at Cambridge, he had decided to apply for a commission in the army, filling in the required E536 form ‘Questionnaire for a candidate for first appointment to a Commission in the Militia, Yeomanry, Cavalry or Volunteers’. Citing his height to be 5 ft 11¾ inches, he had applied to and been accepted for a volunteer militia battalion, the Princess of Wales’s Own Yorkshire Regiment. In this he was following in the footsteps of his ancestor, Sir Christopher Sykes, who in 1798 had raised his own volunteer militia, the Yorkshire Wolds Gentlemen and Yeomanry Cavalry, to help defend the neighbourhood in case of an invasion by Napoleon. Though Mark had done some training with the Regiment in 1898 and 1899, it must still have come as a shock to hear, in the middle of his Michaelmas Term, that they were to be mobilized to serve in South Africa.

‘I now have to go to South Africa’, he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley, ‘which is the most infernal nuisance.’ 3It was a nuisance compounded by the fact that his mother’s debtors were once again clamouring for payment and Mark, fearful that his father was immovable in his refusal to pay up, felt himself bound to step in to prevent the whole estate going ‘to the thieves’ shelter’. 4Such a disaster was not inconceivable, since the sums involved were huge, the entire debt being calculated at £120,000. 5‘[I]f I make myself liable for all these immense sums,’ he wrote to Edith, ‘and no arrangement can be made with my father, with the Estate duty added to all, I shall stand in a somewhat precarious position’. What he found most humiliating, however, was ‘to be constantly arguing on a hypothesis of my father’s death which is to me the most loathsome feature of my repulsive affairs’. 6

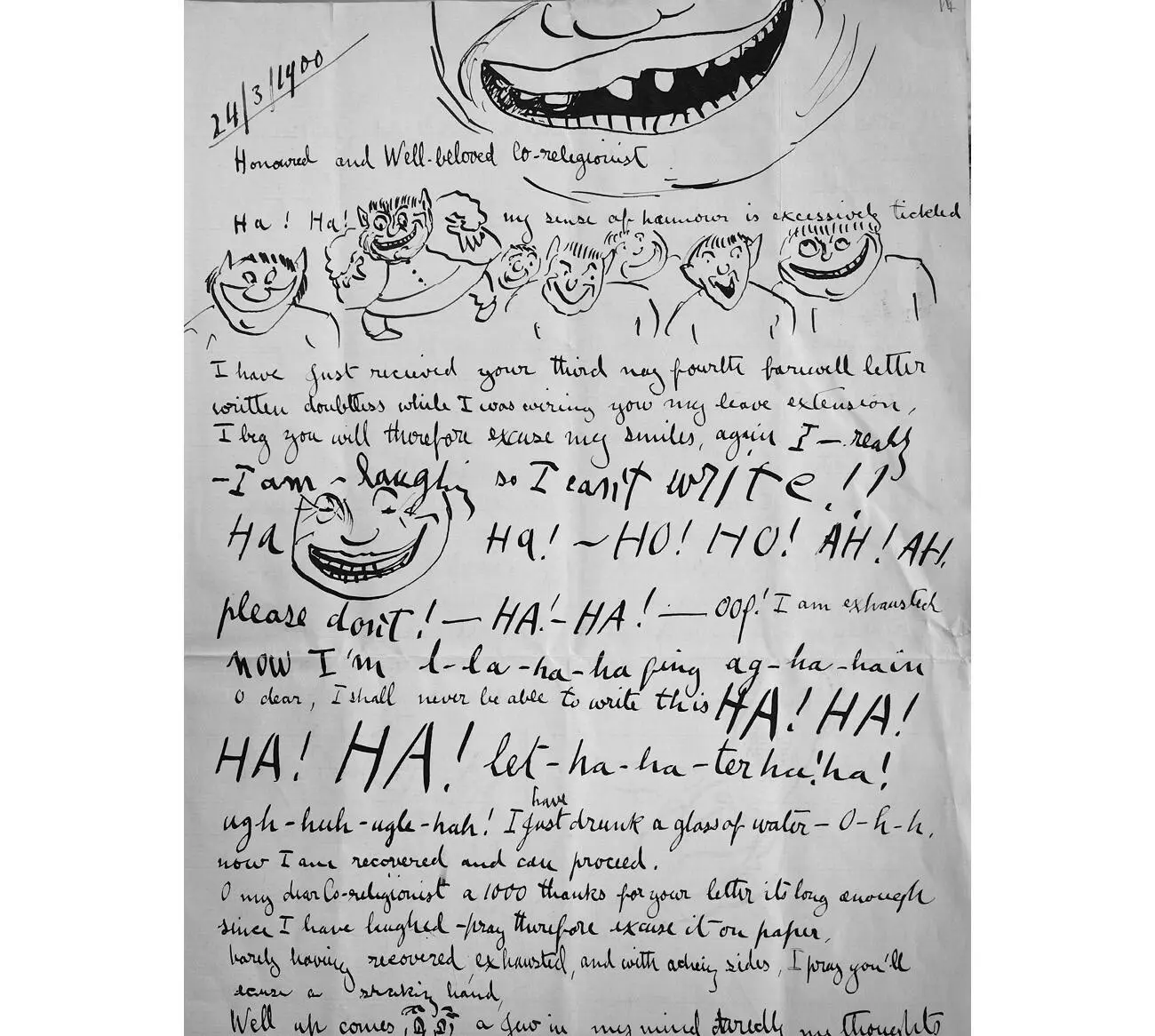

Over the next two months Mark fought hard to reach a settlement that would be agreeable to all parties, while simultaneously having to be prepared for his leave to be cancelled, and his subsequent departure for South Africa. The number of false starts was marked by the numerous letters of farewell he received from Edith.

In return he kept her entertained with tales of his daily life. He was at Sledmere at the end of March for his coming of age, a very muted affair owing to the war.

These last days have seen me amusing myself by reading old books and arranging a room for me to sit in … I have been receiving piles of congratulatory telegrams and letters concerning my coming of age, mostly of this description …

‘13 Queer St.

Dear Sir,

I hasten to congratulate you on your majority, should you Sir require any small temporary loan from 5 to 20,000 pounds etc, etc …’

I received a silver inkstand from the labourers, a very pretty thing, where at I was very pleased. 7

He also amused her with some of the nonsense written about him in the local papers.

By the way, it never rains but it pours … an extract from the Yorkshire Evening Post. ‘Mr Mark Sykes who has just come of age … is a fine singer and can tell a yarn with anyone.’ Fine Singer!! I’faith a fine singer, that should amuse you. See me sing

Читать дальше