(1) Return at once important.

(2) Must return at once father will not settle.

(3) Absolutely necessary your return will explain on arrival.

‘Having read these,’ he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley, ‘I replied that I could not return and proceeded to the Custom House where I was delayed some two hours. At length I proved in different ways viz (by 20 francs) that I was neither an Armenian travelling on a forged passeporte [ sic ], or an English conspirator or an importer of Dynamite …’ He then boarded a Russian steamer bound for Jaffa, carrying 800 Russian pilgrims in the hold: ‘when I went into the hovel that does duty for a Saloon,’ he told Cholmondeley, ‘I found the Russian Skipper blind drunk with two lady friends from the shore’.

He did not, he continued, expect it to be ‘a pleasant voyage as I am the only other passenger’. 4

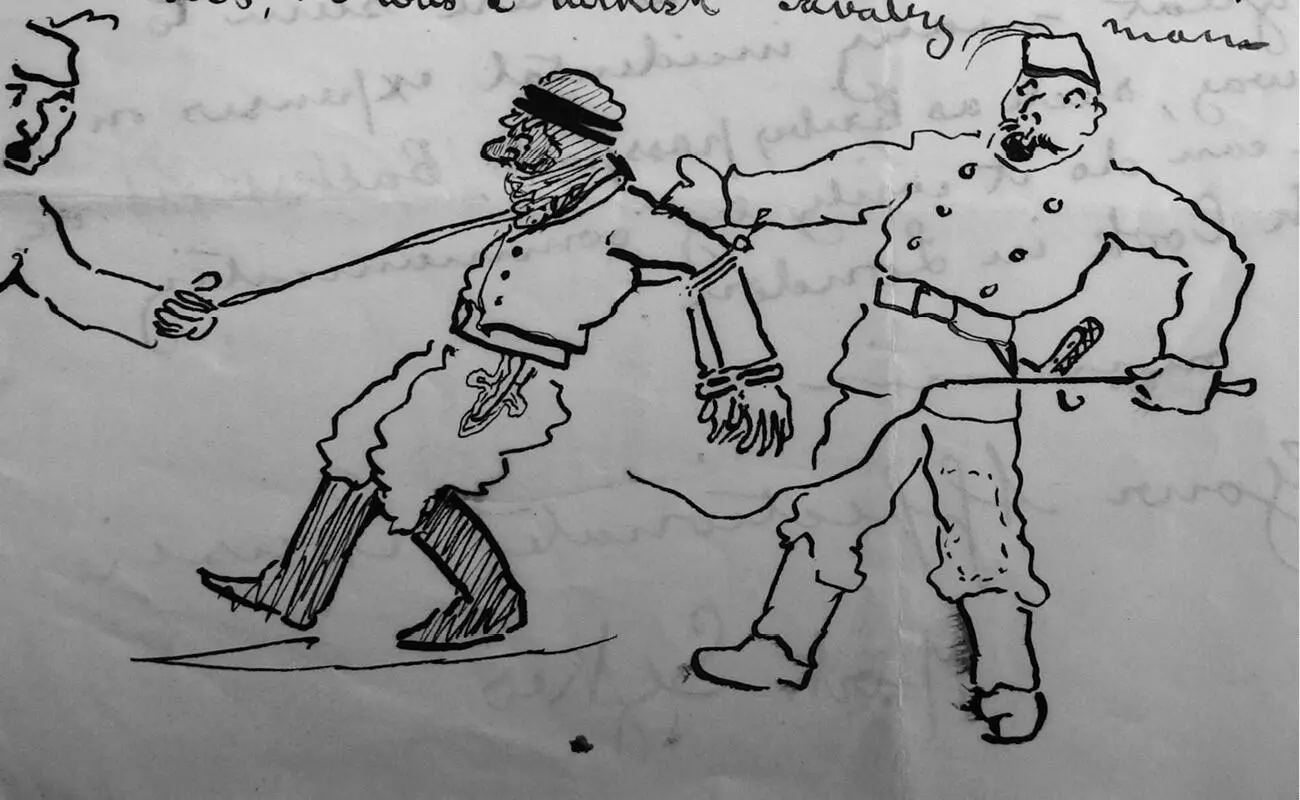

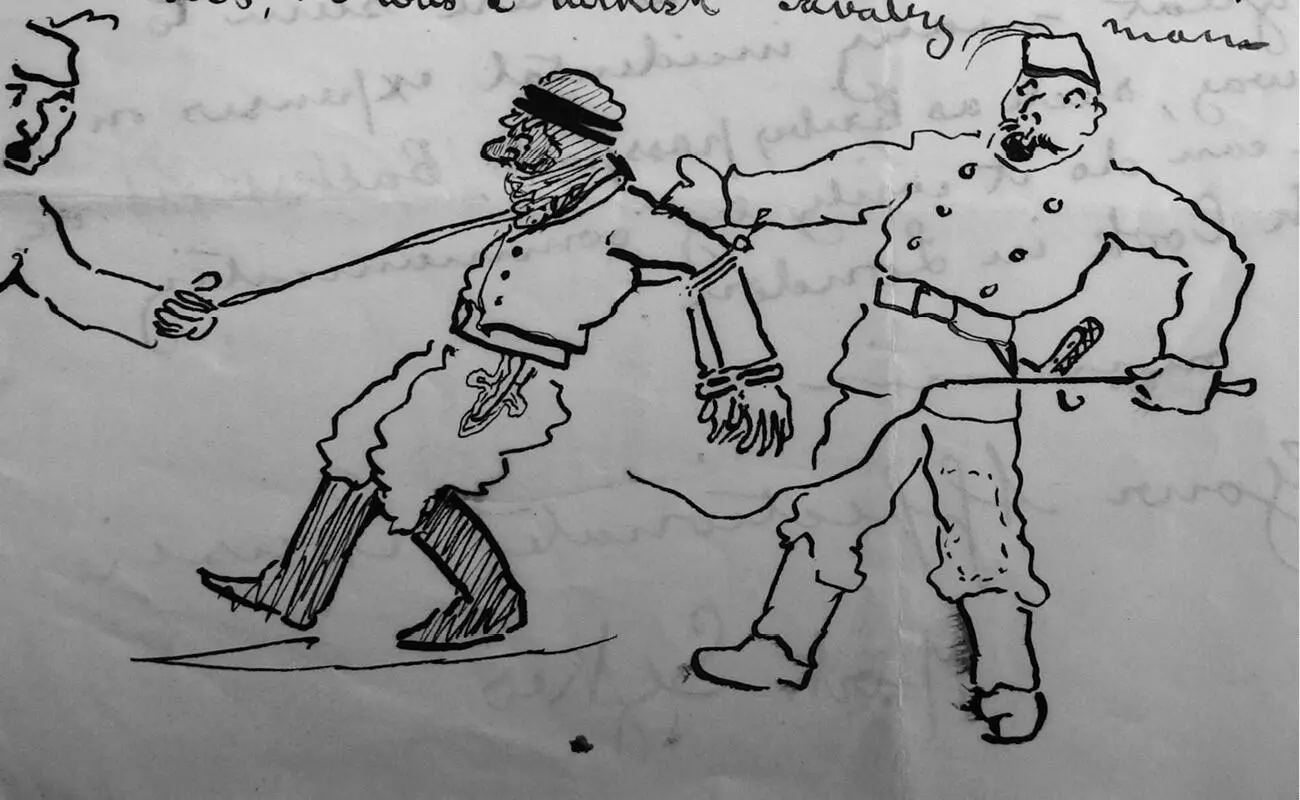

On arrival in Jaffa Mark took the daily train to Jerusalem, operated by the French company Société du Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa à Jérusalem et Prolongements. It was an uneventful journey, bar one incident, which both amused and impressed him: ‘when the train reached a station called Ramleh,’ he reported to Cholmondeley, ‘a shot was fired, and presently a man appeared tied up like this (drawing),

he was a Turkish cavalryman. It turned out that he had had a quarrel with a farmer two years ago, he had been looking for him ever since, found out where he was, obtained leave to go to Ramleh and shot him in the station. He then gave himself up saying he had done what he wanted and they might do what they liked.’ 5

In Jerusalem, Mark was greeted by an old friend, Sheik Fellah, a Bedouin of the Adwan Tribe in Ottoman Syria, whom he had previously met on his travels with his father: ‘the old Sheikh recognized me,’ he told Cholmondeley, ‘and shouted to the crowd that I was his son’. 6

They then set off north-east for Jericho, close to the river Jordan, where on 10 March they picked up the rest of the party, consisting of a dragoman, the traditional Ottoman guide, a cook, a native servant, five muleteers and an Armenian photographer who was to spend one day with them photographing Sheikh Fellah’s camp at El Hammam. ‘The people were wild and interesting,’ wrote Mark. ‘The Arabs, every man of whom carried a weapon of some sort, struck terror into the heart of the Armenian. They dug him in the ribs with a pistol, whereat he wept, upset his camera, and remembered he had pressing business at Jericho. He wanted to return at once, but I persuaded him to take four photographs.’ 7

Sheikh Fellah’s nephew, Sheikh ‘Ali, invited them for lunch. ‘The food consisted of a huge bowl of meat and rice,’ Mark recorded, ‘into which I and another guest, who was a holy dervish, first dipped our hands. The holy man showed no dislike to eating with so ill-omened a kafir as myself, but told my dragoman that he had known an Englishman with a long beard who spoke Arabic, had read all Arabic books and wrote night and day without eating or sleeping, and whom he had nursed at Salt during an illness. His name was Richard Burton. In return that evening I invited the two Sheikhs to dine with me. Fellah is a great friend of the Franciscans, having a room of his own in their convent in Jerusalem, and so had learnt the use of knife and fork, but ‘Ali, true son of the desert, was much puzzled by the Frankish eating tools, and invariably took the spoon from the dish for his own use.’ 8

Mark’s travels progressed smoothly until, on 13 March, he reached ‘Ammân, today the capital of Jordan, the site of which is described in the 1903 edition of Murray’s Handbook as being ‘weird and desolate … The place is offensive too from its filth. The abundant waters attract the vast flocks that roam over the neighbouring plains, and the deserted palaces and temples afford shelter to them during the noon-day heat; so that most of the buildings have something of the aspect and stench of an ill-kept farm-yard.’ 9Here the Circassian military caused problems for Mark’s party, insisting that he did not hold the correct travel permits, and though he managed to get as far as Jerash, a ten-hour ride away, he was held up there for a number of days. On 19 March, when he was finally able to continue his journey towards the ancient biblical city of Bosrah, he was lucky enough to meet the Hajj pilgrimage on its way to Mecca, an experience that very few Westerners would then have had.

‘It was an extraordinary sight,’ he wrote, ‘… miles it seemed to be of tents of every shape and form: military bell tents; black Bedawîn tents; enormous square tabernacles of green, red, and white cloth; tiny tentes d’abri , some only being cotton sheets on poles three feet high. The gathering of people would be almost impossible to describe. In one place I saw a family of wealthy Turks in frock coats, all talking French; close by, a green-turbaned Dervish reading the Korân; a little further on, the Pasha of the Hajj, in a fur-trimmed overcoat, giving orders to a dashing young Turkish subaltern; here, two men who owned a most gorgeous palanquin which they were in hopes of letting to some rich lady from Cairo, were fighting over the fodder of the two splendid camels that carried it; there, Arab stallions were squealing and kicking at the mules of the mounted infantry contingent … There were at least 10,000 civilians in the pilgrimage. Among them were many whole families of hajis, children and women being in almost as great numbers as men … The enormous procession, at least four miles long, glittering with red, green and gold saddles and ornaments, was an impressive sight that I shall never forget; for every animal had at least four bells on its saddle or neck. I could hear it like that sound of the sea …’ 10

For Mark, the country of the Haurân was the most interesting part of his trip, known as it was for the number, extent and beauty of its ruins. It was the home of the Druses, a monotheistic religious and social tribe whose sheikhs formed a hereditary nobility that preserved with tenacity all the pride and state of their order. The correct letters of introduction were vital for the progress of a traveller through their lands, but once obtained they would be received with the greatest hospitality, with no requirement of compensation. ‘When I arrived at Radeimeh,’ he wrote, ‘the Sheikh was particularly hospitable, not only giving me dinner but feeding all my muleteers and servants. The sight of McEwen sitting between two Druse Sheikhs and being solemnly crammed by them with rice and bread dipped in oil and pieces of mutton was, to say the least, quaint. After … the Sheikh took my dragoman aside and told him that there was a certain place in the desert named Heberieh, where there were many arms, legs and fingers sticking in the stones.’ 11No European had yet visited this strange place, which he said was a long ride away and would need an escort of at least fifteen men. ‘I decided to visit the place the next day,’ wrote Mark, ‘visions of some ancient quarry or isolated sculpture rising before me, and as there was no mention of anything of the sort in Murrays Handbook, I had great hopes of making a discovery.’ 12

At four the following morning, the party set off and after two hours’ riding found themselves in country which Mark described as being some of the most extraordinary he had ever seen in the course of his extensive travels in four continents. He wrote of it as ‘a fireless hell; nothing else could look so horrible as that place. Enormous blocks of black shining stones were lying in every direction; in places we passed great ridges some 20 feet high and split down the centre. One of these stretched over a mile and looked like a gigantic railway cutting. There was neither a living thing in sight, nor the least scrub to relieve the eye from the monotony of the slippery black rocks. My dragoman said to me “I tink one devil he live here.”’ After four hours’ hard riding through this inferno, the party reached an open space in the centre of which was a hill. The Druses announced that they had reached their destination.

Читать дальше