The London Evening Post made a similar complaint: ‘The most scandalous parsimony prevailed, and every mark of disrespect was shown to those members who did attend. Not half the quantity of cloaks, scarfs, or hatbands were provided – great complaints were made but the answer, was, “it would have been too expensive to have furnished more.” Colonel Barré justly observed, “it is not a reign to complain in”.’ 9Chatham had evidently complained too much.

Those who thought they would see the parliamentary leaders assembled en masse found instead only about forty peers and twenty MPs among the many hundreds of people attending the ceremony. There was Rockingham, the foremost opposition politician; there Edmund Burke, his right-hand man; there General Burgoyne, the soldier turned opposition MP – but they were there ‘more to vex the King’s Ministers than to honour the memory of the Earl’. 10Only one member of the government was present, Lord Amherst, who had commanded the army under Chatham, and only one member of the Royal Family, the Duke of Gloucester, the King’s estranged younger brother. There were no Sheriffs, no Masters in Chancery in their gowns, no judges or Privy Councillors. The Lord Mayor was missing, as was the Speaker of the House of Commons, and there was not ‘a sufficient number of Baronets to walk by themselves’. 11

Still, the crowds had witnessed a solemn procession and a major event. Some of them might even have noticed the Chief Mourner, walking behind the coffin, the late Earl’s second son, another William Pitt. On his left was his brother-in-law, Lord Mahon, and on his right his uncle, Thomas Pitt. With his mother choosing to stay at home rather than grieve in public and his elder brother at sea on the expedition to reinforce Gibraltar, the nineteen-year-old William performed his first public duty, walking behind the coffin of the father who had doted on him. That night he wrote to his mother:

Harley Street

June 9th, 1778

My Dear Mother

I cannot let the servants return without letting you know that the sad solemnity has been celebrated so as to answer every important wish we could form on the subject. The Court did not honour us with their countenance, nor did they suffer the procession to be as magnificent as it ought; but it had notwithstanding everything essential to the great object, the attendance being most respectable, and the crowd of interested spectators immense. The Duke of Gloucester was in the Abbey. Lord Rockingham, the Duke of Northumberland, and all the minority in town were present … All our relations made their appearance … I will not tell you what I felt on this occasion, to which no words are equal; but I know that you will have a satisfaction in hearing that Lord Mahon as well as myself supported the trial perfectly well and have not at all suffered from the fatigue …

I hope the additional melancholy of the day will not have been too overcoming for you, and that I shall have the comfort of finding you pretty well tomorrow. I shall be able to give you an account of what is thought as to our going to Court.

And I am ever, my dear Mother, your most dutiful and affectionate son,

W Pitt 12

Less than twenty-eight years would pass before William Pitt’s own body would join that of his father beneath the same dark stone slab in the North Transept of Westminster Abbey. In that time, he would equal his father’s fame and popularity while far exceeding his domination of politics and his endurance in office.

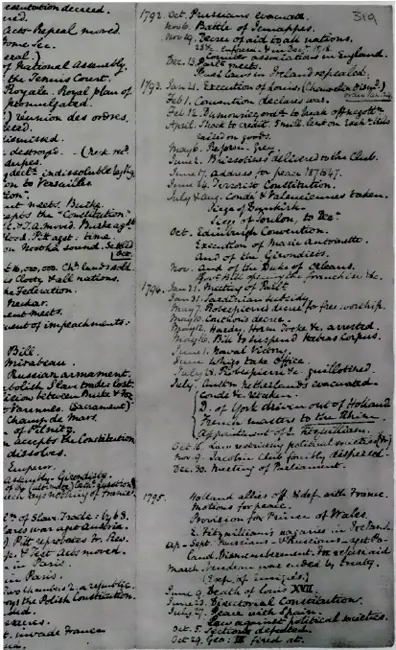

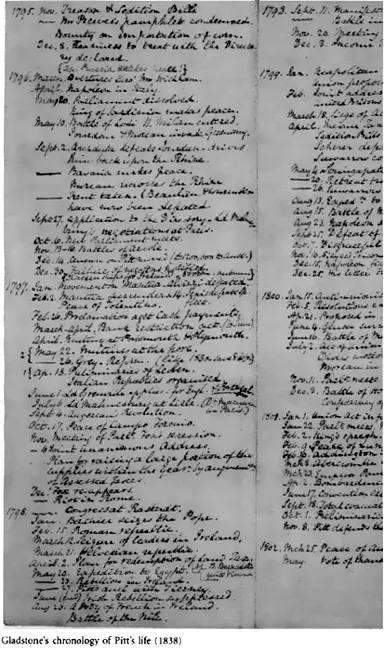

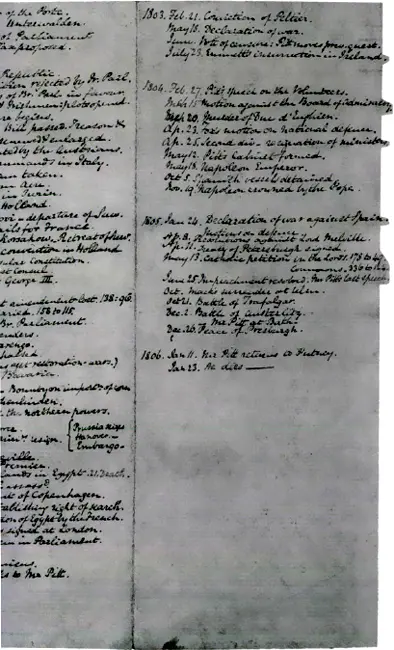

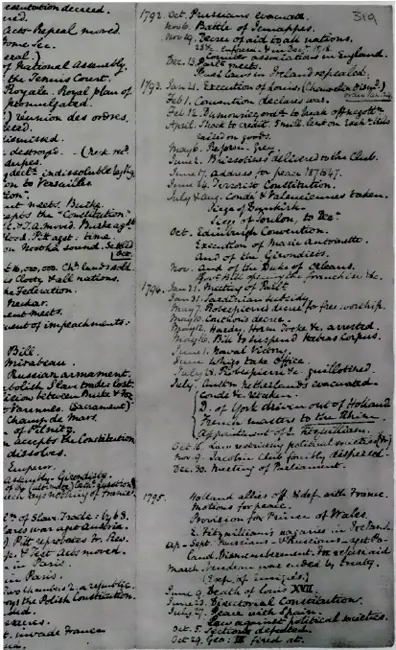

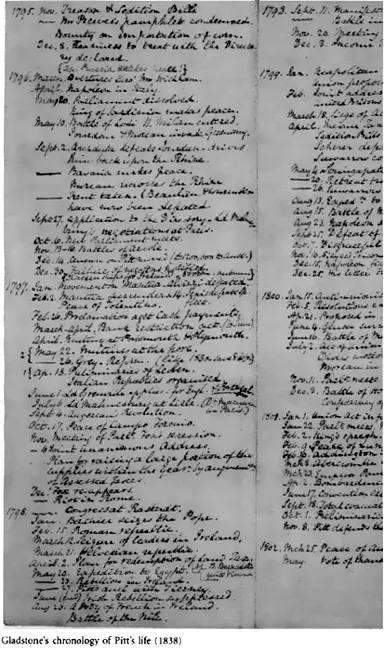

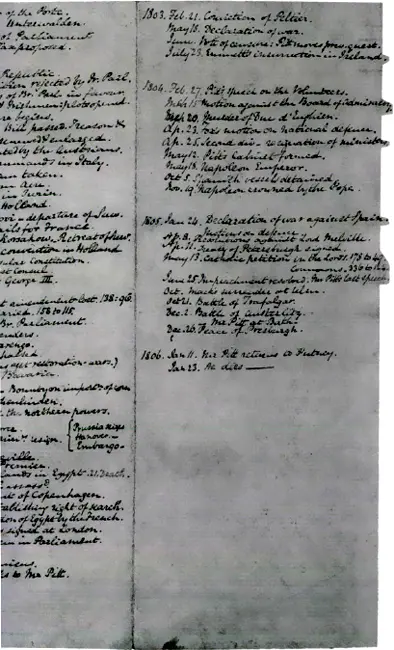

Gladstone’s chronology of Pitt’s life (1838)

PART ONE

‘There never was a father more partial to a son.’

WILLIAM WYNDHAM GRENVILLE 1

‘He went into the House of Commons as an heir enters his home; he breathed in it his native atmosphere, – he had, indeed, breathed no other; in the nursery, in the schoolroom, at the university, he lived in its temperature; it had been, so to speak, made over to him as a bequest by its unquestioned master. Throughout his life, from the cradle to the grave, he may be said to have known no wider existence. The objects and amusements, that other men seek in a thousand ways, were for him all concentrated there. It was his mistress, his stud, his dice box, his game-preserve; it was his ambition, his library, his creed. For it, and it alone, had the consummate Chatham trained him from his birth.’

LORD ROSEBERY 2

IT WOULD SCARCELY BE POSSIBLE to imagine a more intensely political family than the one into which William Pitt was born on 28 May 1759. On his father’s side, his great-grandfather, grandfather and uncle had all been Members of Parliament. His father, twenty-five years an MP, was now the leading Minister of the land. On his mother’s side, that of the Grenville family, one uncle was in the House of Lords, and two others were in the Commons, one of them to be First Lord of the Treasury by the time the infant William was four years old. An understanding of Pitt’s extraordinary political precocity requires us to appreciate the unusual circumstances of a family so wholeheartedly committed to political life.

It was in the year of William’s birth that the career of his father, still also plain William Pitt, approached its zenith. Three years into what would later be known as the Seven Years’ War, in which Britain stood as the only substantial ally of Prussia against the combined forces of France, Austria, Russia, Saxony and Sweden, the elder Pitt had become the effective Commander-in-Chief under King George II of the British prosecution of the war. In his view the war had arisen from ‘a total subversion of the system of Europe, and more especially from the most pernicious extension of the influence of France’. 3He was not nominally the head of the government, the position of First Lord of the Treasury being held by his old rival the Duke of Newcastle, but he was the senior Minister in the House of Commons. Through his powerful oratory he dominated both Parliament and the Ministry, and was acknowledged as the effective leader of the administration. As Newcastle himself said in October of that year: ‘No one will have a majority at present against Mr. Pitt. No man will, in the present conjuncture, set his face against Mr. Pitt in the H. of Commons.’ 4

From taking office at the age of forty-eight in 1756 as Secretary of State for the Southern Department, *with a brief interruption of two months during the Cabinet crisis of 1757, Pitt had become the principal source of ministerial energy in both organising for war and in preparing a strategy for Britain to do well out of it. It was Pitt who gave detailed instructions on the raising and disposition of the troops and the navy, and Pitt who insisted on and executed the objective of destroying the empire of France. As the French envoy, François de Bussy, was to complain to the leading French Minister the Duc de Choiseul after meeting Pitt in 1761: ‘This Minister is, as you know, the idol of the people, who regard him as the sole author of their success … He is very eloquent, specious, wheedling, and with all the chicanery of an experienced lawyer. He is courageous to the point of rashness, he supports his ideas in an impassioned fashion and with an invincible determination, seeking to subjugate all the world by the tyranny of his opinions, Pitt seems to have no other ambition than to elevate Britain to the highest point of glory and to abase France to the lowest degree of humiliation …’ 5

Читать дальше