The fallen coffee berries are now clean. They are still the color and size of cherries. The red exterior is a hard pod, or polpa . Inside of each pod are two beans, each of which is covered with a skin of its own. The water which has fallen with the berries carries them on to the machine called the despolpador , which breaks the outside pod and frees the beans. Long tubes, called “driers,” now receive the beans, still wet and with their skins on them. In these driers the beans are continually agitated in hot air.

Coffee is very delicate. It must be handled carefully. Therefore the dried beans are lifted by the cups of an endless-chain elevator to a height whence they slide down an inclined trough to … the coffee machine house.

The beans were then carried by a second elevator to the processing plant. The first machine they encountered was a ventilator, a series of vibrating sieves that let the coffee beans slip through but trapped any remaining sticks, leaves, and pebbles, impurities that would break the next machine.

Another endless-chain elevator carries the beans to a height whence they fall through an inclined trough into the descascador , or “skinner.” It is a highly delicate machine; if the spaces between are a trifle too big, the coffee passes without being skinned, while if they are too small, they break the beans.

Another elevator carries the skinned beans with their skins to another ventilator, in which the skins are blown away.

Still another elevator takes the now clean beans up and throws them into the “separator,” a great copper tube two yards in diameter and about seven yards long, resting at a slight incline. Through the separator tube the coffee slides. As it is pierced at first with little holes, the smaller beans fall through them. Further along it is pierced with larger holes, and through these the medium-sized beans fall; and further still along are yet larger holes for the large, round beans called “mocha.” Each grade falls into the hopper, beneath which are stationed weighing scales and men with coffee sacks. As the sacks fill up to the required weight, they are replaced by empty ones; and the tied and labeled sacks are shipped to Europe.

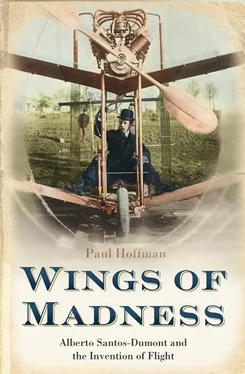

As a boy, Santos-Dumont spent whole days watching the machines and teaching himself to fix them. They were always breaking down.

In particular, the moving sieves were continually getting out of order. While they were not heavy, they moved back and forth horizontally at great speed and took an enormous amount of motive power. The belts were always being changed, and I remember the fruitless efforts of all of us to remedy the mechanical defects of the device.

Now, is it not curious that these troublesome shifting sieves were the only machines at the coffee works that were not rotary? They were not rotary, and they were bad. I think this put me as a boy, against all agitating devices in mechanics, and in favor of the more easily handled and more serviceable rotary movement….

This was a prejudice that would serve him well when he built flying machines as an adult.

Alberto was also the handyman around the house. His mother’s sewing machine often jammed, and she expected him to stop whatever he was doing and repair it. When arms or legs fell off his sisters’ dolls, he was the one who reattached them. When the wheels on his brothers’ bicycles started to wobble, he was the one who realigned them.

Alberto was a loner and a dreamer, preferring the company of plantation machinery to a meal with his family. The atmosphere in Alberto’s house was often tense. His mother was deeply religious and superstitious, and his father, a man of reason and science, openly mocked her beliefs at family dinners. Although Henrique was pleased by his youngest son’s fascination with technology, he did not understand why Alberto had no interest in hunting, roughhousing, and the other manly activities that his brothers liked. Alberto never joined the men on all-day horseback expeditions and picnics to the far reaches of the land.

At night he stayed up late reading. His father, who had received his engineering training in Paris at the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Métiers, had stacks of books lying around the house, in French, English, and Portuguese. Alberto paged through most of them, even the technical manuals. His favorites were science fiction. He loved Jules Verne’s vision of a sky populated with flying machines and had read all his novels by the age of ten. He learned from his father’s engineering texts that the hot-air balloon had been invented in 1783, by Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier, papermakers in Annonay, France, a town in the Rhône valley forty miles from Lyons. The brothers had constructed a large pear-shaped envelope, from paper or silk, with an aperture at the base so that it could be inflated with smoke from burning straw. One account said that the inspiration had come from Joseph’s aimlessly tossing the conical paper wrapping of a sugarloaf into the fireplace and then being surprised to see it rise up the chimney without igniting. Another story attributed it to his watching his wife’s camisole levitate after she hung it in front of the hearth to dry.

The fact that “millions of people” over the ages must have observed similar phenomena, one commentator noted, “and had not derived anything practical therefrom only enhances the glory of those who in such well-worn tracks did make a discovery.” The earliest suggestion of aerostation, as ballooning was called, predated the Montgolfiers by two thousand years but was probably not authentic. In Noctes Atticae (“Attic Nights”), the Roman writer Aulus Gellius described a flying dove constructed by Archytas of Tarentum, a Pythagorean mathematician in the fourth century B.C. It was a “model of a dove or pigeon formed in wood and so contrived as by a certain mechanical art and power to fly: so nicely was it balanced and put in motion by hidden and enclosed air.” Although the “hidden and enclosed air” suggested an anticipation of the hot-air balloon, it was doubtful that a hollow wooden bird would have been light enough to ascend. It was more likely that the dove’s apparent flying was a mechanical trick accomplished by invisible wires.

The physical basis of aerostation was as simple as the Montgolfiers’ solution of imprisoning hot air in a bag: The balloon floated because it weighed less than the equivalent volume of air, just as a seafaring ship floated because it weighed less than the equivalent volume of water. But the analogy between ship and balloon worked only if one accepted the idea that the atmosphere weighed something, and that was not known until Galileo’s time, when Evangelista Torricelli, the inventor of the barometer, demonstrated that the atmosphere had a measurable weight that decreased with elevation. Another seventeenth-century investigator, Otto von Guericke in Magdeburg, Germany, invented a vacuum pump for creating the “rarefied air” found at very high elevations. In 1670, Francesco de Lana-Terzi, an Italian Jesuit priest, conceived of a man-carrying vessel supported by four huge hollow-copper spheres devoid of air. Because the evacuated spheres would be lighter than the air they displaced, he expected the vessel to rise through the atmosphere like an air bubble ascending through water. The mathematically sophisticated priest calculated that the spheres had to be twenty-five feet in diameter and 1/ 225of an inch in thickness. When his physicist friends warned him that spheres this thin would collapse when the air was withdrawn from them, he responded—according to engineering historian L. T. C. Rolt—“that his was only a theoretical exercise, arguing that since God had not intended man to fly, any serious practical attempt to flout His designs must be impious and fraught with peril for the human race. One suspects that the Jesuit fathers may have had a serious talk with their scientifically minded son and that he made this disclaimer because he could smell faggots burning.”

Читать дальше