For Max & Eliza & Olivia

Cover

Title Page

Dedication For Max & Eliza & Olivia

Epigraph Sometimes Louis saw in his sons a mirror that reflected the best of who he was and he was in awe; other times he hoped to see nothing of himself and would insist on molding the opposite, by force if necessary. Fatherhood is the bending of that alpha and that omega, with the wobbly heat of our own fathers mixed in. We love and hate our boys for what they might see. —A. N. Dyer, The Spared Man

Part I

Chapter I.i

Chapter I.ii

Chapter I.iii

Part II

Chapter II.i

Chapter II.ii

Chapter II.iii

Part III

Chapter III.i

Chapter III.ii

Chapter III.iii

Part IV

Chapter IV.i

Chapter IV.ii

Chapter IV.iii

Part V

Chapter V.i

Chapter V.ii

Chapter V.iii

Part VI

Chapter VI.i

Chapter VI.ii

Chapter VI.iii

Part VII

Chapter VII.i

Chapter VII.ii

Chapter VII.iii

Part VIII

Chapter VIII.i

Chapter VIII.ii

Chapter VIII.iii

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by David Gilbert

Copyright

About the Publisher

Sometimes Louis saw in his sons a mirror that reflected the best of who he was and he was in awe; other times he hoped to see nothing of himself and would insist on molding the opposite, by force if necessary. Fatherhood is the bending of that alpha and that omega, with the wobbly heat of our own fathers mixed in. We love and hate our boys for what they might see.

—A. N. Dyer, The Spared Man

ONCE UPON A TIME, the moon had a moon. This was a long time ago, long before there were sons who begged their fathers for good-night stories, long before there were fathers or sons or stories. The moon’s moon was a good deal smaller than the moon, a saucer as compared to a platter, but for the people of the moon this hardly mattered. They maintained a constant, almost mystic gaze on their moon. You might ask these people—not quite people, more like an intelligent kind of eggplant, their roots eternally clenched—What about the nearby earth, with its glorious blues and greens and ever-changing swirls of white? Surely that gathered up some of their attention? Actually, not at all. The earth to them seemed a looming presence, vaguely sinister, like something that belonged to a sorcerer. This brings up another question: how did the creatures of the earth feel about its two moons? Well, to be honest, life at that time was rather pea-brained, though recently scientists have discovered a direct evolutionary link between those moons and the development of binocular vision in the Cambrian slug .

But one day—for this is a story and there must be a one day—the moon’s moon appeared bigger than normal in the sky, which the wise men of the moon chalked up to something they called intergravitational bloat. Regardless, it shone with even more brilliance, only to be outdone the next evening, when the circumference had quintupled. Nobody was yet frightened; they were too much in awe. But by the tenth day, when the moon’s moon resembled the barrel of a train bearing down on them, the people started to worry. This can’t be happening. What they loved more than anything suddenly seemed destined to kill them. Oh mercy. Oh dear. A resigned kind of panic set in, as they gripped their roots extra tight and prepared for the inevitable impact, which would have come on the twenty-first day except that the moon’s moon passed overhead like a ball slightly overthrown. Thank heavens it missed, the people sighed. Then they turned their heads and followed its course and soon realized its true path: the distant bull’s-eye of earth. It seemed they were not the players here, merely the spectators. On the twenty-fourth day, roughly sixty-five million years ago, the moon’s moon traveled its last mile and a great yet silent blast erupted from the lower hemisphere of earth. And that was it. Their moon was gone. In its place a cataract of gray gradually blinded all those blues and greens and swirls of white .

The sky where their moon once hung now seemed dark and injured, its color the color of a bruise. A new kind of longing set in as they stared at earth. Someone was the first to let go, likely the most depressed. To his amazement, instead of withering, always the assumed prognosis, he began to float—not only float but rise up and drift toward the distant grave site of their beloved moon. “We’ve all been holding on,” he shouted down, newly prophetized, “all this time just holding on.” Was this suicide or deliverance? the wise men of the moon debated while someone else let go, and then another, three then five then eight rising up into the sky, their eyes casting a line toward earth and a hopeful reunion with their moon. Before any opinion could be agreed upon, the horizon shimmered with thousands of fellow travelers, the moon like a dandelion after a lung-clearing fffffffffffffff. The surface grew paler until eventually only one soul remained behind, a child, specifically a boy. Every second he was tempted to join the others, but he was stubborn and mistook his grip for freedom. Friends and family slowly faded from sight, their pleas losing all echo, and many years later, when the sky no longer included their memory, this boy, now a young man, lowered his head and contemplated the ground. Soon he took his first steps, dragging his cumbersome roots across dusty lunar plains, certain that what was lost would soon be eclipsed by whatever he would find .

But that will have to wait until tomorrow night .

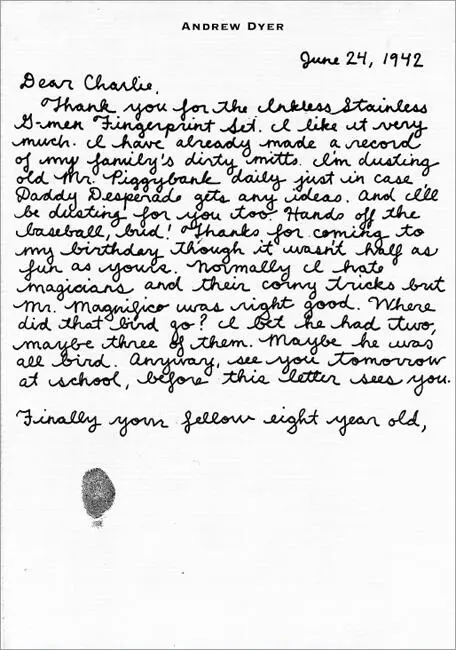

AND THERE HE SAT, up front, all alone in the first pew. For those who asked, the ushers confirmed it with a reluctant nod. Yep, that’s him. For those who cared but said nothing, they gave themselves away by staring sideways and pretending to be impressed by the nearby stained glass, as if devotees of Cornelius the Centurion or Godfrey of Bouillon instead of a seventy-nine-year-old writer with gout. Rumor had it he might show. His oldest and dearest friend, Charles Henry Topping, was dead. Funeral on Tuesday at St. James on 71st and Madison. Be respectful. Dress appropriately. See you there. Some of the faithful brought books in hopes of getting them signed, a long shot but who could resist, and by a quarter of eleven the church was almost full. I myself remember watching friends of my father as they walked down that aisle. While they glimpsed the Slocums and the Coopers and over there the Englehards—hello by way of regretful grin—a number of these fellow mourners baffled them. Were those sneakers? Was that a necklace or a tattoo; a hairdo or a hat? It seemed death had an unfortunate bride’s side. Once seated, all and sundry leafed through the program—good paper, nicely engraved—and gauged the running time in their head, which mercifully lacked a communion. There was a universal thrill for the eulogist since the man up front was notoriously private, bordering on reclusive. Excitement spread via church-wide mutter. Thumbs composed emails, texts, status updates, tweets. This New York funeral suddenly constituted a chance cultural event, one of those I-was-there moments, so prized in this city, even if you had known the writer from way back, knew him before he was famous and won all those awards, knew him as a strong ocean swimmer and an epic climber of trees, knew his mother and his father, his stepfather, knew his childhood friends, all of whom knew him as Andy or Andrew rather than the more unknowable A. N. Dyer.

Читать дальше