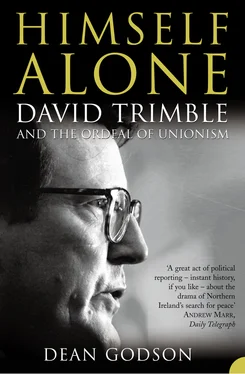

DEAN GODSON

HIMSELF ALONE

DAVID TRIMBLE

AND THE ORDEAL OF UNIONISM

For my mother above all

but not forgetting Paul, Greta, John, Evelyn, Charlie and Gill

I am Ulster, my people an abrupt people

Who like the spiky consonants in speech

And think the soft ones cissy; who dig

The k and t in orchestra, detect sin

In sinfonia, get a kick out of

Tin cans, fricatives, fornication, staccato talk,

Anything that gives or takes attack,

Like Micks, Tagues, tinkers’ gets, Vatican.

An angular people, brusque and Protestant,

For whom the word is still the fighting word,

Who bristle into reticence at the sound

Of the round gift of the gab in Southern mouths.

Mine were not born with silver spoons in gob,

Nor would they thank you for the gift of tongues;

The dry riposte, the bitter repartee’s

The Northman’s bite and portion, his deep sup

Is silence; though, still within his shell,

He holds the old sea-roar and surge

Of rhetoric and Holy Writ.

W. R. Rodgers; from ‘Epilogue’ in Poems ,

Michael Longley (Oldcastle,

Co. Meath, 1993), pp. 106–7

‘Whatever an Ulsterman may be, he is certainly never charming, and of that fact, no one is more fully aware than the Ulsterman himself.’

F. Frankfort Moore, The Truth about Ulster

(London, 1914), p. 102

‘I’ve changed, you know.’

David Trimble to his old friend, Professor Herb Wallace,

after signing the Belfast Agreement

‘What do you want for your people?’

‘To be left alone.’

Exchange between Sean Farren, a senior nationalist politician, and David Trimble at Duisburg, in the late 1980s

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1. Floreat Bangoria

2. A don is born

3. In the Vanguard

4. Ulster will fight

5. The changing of the Vanguard

6. Death at Queen’s

7. He doth protest too much

8. Mr Trimble goes to London

9. Framework or straitjacket?

10. The Siege of Drumcree (I)

11. Now I am the Ruler of the UUP!

12. The Establishment takes stock

13. Something funny happened on the way to the Forum election

14. Go West, young man!

15. ‘Binning Mitchell’

16. ‘Putting manners on the Brits’

17. The Yanks are coming

18. The Siege of Drumcree (II)

19. Fag end Toryism

20. The unlikeliest Blair babe

21. The pains of peace

22. When Irish eyes are smiling

23. Murder in the Maze (or the way out of it)

24. Long Good Friday

25. ‘Let the people sing’

26. A Nobel calling

27. The blame game speeds up

28. No way forward

29. RUC RIP

30. By George

31. ‘And the lion shall lie down with the lamb’

32. Mandelson keeps his word

33. The Stormont soufflé rises again

34. In office but not in power

35. A narrow escape

36. The luckiest politician

37. Another farewell to Stormont

38. A pyrrhic victory

39. Paisley triumphant

40. Conclusion

Glossary

Index

About the Author

Author’s Note

Notes

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

WILLIAM David Trimble was born on 15 October 1944, at the Wellington Park Nursing Home in Belfast of respectable, lower-middle-class, Presbyterian stock. From his earliest years he was called David, apparently to distinguish himself from his father, William Sr. The gregarious elder Trimble was generally known as ‘Billy’, but his flinty son was to reject all such attempts to turn him into a ‘Davy’ or a ‘Dave’. He remained resolutely ‘David’. This name apparently derives from his paternal grandfather, George David Trimble, born in 1874 and a native of Co. Longford. The earliest Protestant settlement there can be traced back to the reign of James I, though there was an overspill into Co. Longford resulting from subsequent influxes of Scottish Presbyterians into Ulster at the end of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Indeed, at its pre-Famine peak, the Protestant community numbered around 14,000 and the 1831 census suggests that it comprised 9.5% of the population. As late as 1911, in the parish of Clonbroney where the Trimbles lived, Protestants comprised 18.3% of the population. 1 It is not known when the Trimbles – a variation of the Scottish Lowland name of Turnbull – arrived in Co. Longford. 2 But what is certain is that David Trimble’s own line of descent can be traced back to the end of the 18th century (he is not related to the Co. Fermanagh Trimbles, whose descendants own the famed Impartial Reporter and Farmers’ Journal. By coincidence, his wife is part of that extended family). Like most Protestants, the Co. Longford Trimbles and the families they married into – the Smalls, the Twaddles, the Gilpins and the Eggletons – were farmers, with a few ploughmen, stewards and underagents amongst them. The first available record is of one Alexander Trimble (DT’s great-great-grandfather) who farmed in Sheeroe, Co. Longford. His son, also called Alexander (DT’s great-grandfather), lived from 1826 to 1904 and had eight children of whom the above-mentioned George David (DT’s grandfather) was the youngest. According to Griffith’s valuation of property in Ireland, conducted in the 1850s and 1860s, Alexander Trimble (II) rented a plot from one of the Edgeworths, the main landowners in the area, comprising lands of 11 acres, 3 roods and 16 perches. Its rateable valuation was £9 and 5 shillings, with buildings thereon valued at £1 and 15 shillings. But unlike most Protestants in Co. Longford, who were adherents of the Church of Ireland, the Trimbles were staunch Presbyterians: the parish registers show that George David, DT’s grandfather, was baptised at Tully Presbyterian Church in 1875. They were thus a minority within a minority. History does not record how these Trimbles felt about the Ascendancy, in the shape of the Edgeworth family, nor about the Church of Ireland itself. If they keenly felt the disabilities long imposed upon Dissenters, it echoed down the years in odd ways: David Trimble himself never much cared for the traditional Unionist establishment.

The world of the Trimbles, like those of so many smallholders, would have been far removed from the elegiac evocations of ‘Big House’ Protestant life described by Somerville and Ross or Elizabeth Bowen. Especially during the latter half of the 19th century, they became increasingly vulnerable. There were a number of reasons for this: changing patterns in the rural economy, which led to the disappearance of farm servanthood and labouring jobs; difficulty in finding suitable local spouses, sometimes leading to intermarriage with Catholics and to conversion; and the lure of North America. Another, darker explanation for the decline in the Protestant population was the rising tide of Catholic disaffection – which took an increasingly violent form – and the attempts of some of the bigger landlords and of the British Government based in Dublin Castle to appease such anger through a variety of reforms at the Protestant smallholders’ expense. 3 According to J.J. Lee, mid-19th-century Co. Longford was one of the six most disturbed counties in Ireland. David Fitzpatrick further states that in the immediate pre-Partition era, Sinn Fein membership in Co.

Читать дальше