Confronted by the impossibility of matching Branson’s self-proclaimed fortune to finance a team of lawyers, I would have been forced to capitulate and apologise, and inevitably discredit my own book. Fortunately, Max Hastings, the Evening Standard ’s editor, pledged in a prominent article to finance the defence of the piece which his newspaper had published.

At the time I wrote this book, there had been two biographies and one autobiography about Richard Branson. All three benefited from Sir Richard’s vetting and approval. I resisted that blessing. This book is offered as a balanced review of Britain’s most visible entrepreneur, an eager recipient of hero worship, trying to influence practically every aspect of British society, who, in his attempt to market a Virgin lifestyle, seeks the widest possible circle of influence.

Preface to the 2008 Edition

Sir Richard Branson did not appreciate this unauthorised biography when it was originally published in 2000. Indeed, to prevent its publication, he took exception to a critical article which I had written for the London Evening Standard about his first bid for the National Lottery, and decided to issue a writ for defamation against myself, but not against the newspaper. Some interpreted this as an attempt to put me under financial pressure to settle the case in his favour. Had it succeeded, the credibility of this biography would have been destroyed even before its publication. Eventually, without my having offered any concession or agreeing to any of his demands, Sir Richard withdrew his complaint and his case was abandoned. The legacy was twofold. The rulings by Mr Justice Eady and the Court of Appeal during the lengthy hearings of Branson vs Bower have become enshrined as a cornerstone of British libel law. Newspapers, publishers, journalists and authors are, in some circumstances, now protected in publishing critical comment so long as the author wrote in good faith.

The second legacy was the generation of enormous publicity, which propelled the success of this book. Following his recent successes in the libel court, Sir Richard had apparently anticipated another scalp. Yet over the following months many concluded that he had scored a spectacular own-goal.

Throughout the world, those interested in the Branson phenomenon were alerted to an alternative interpretation of a remarkable career. Over the past eight years I have received a steady stream of enquiries and congratulations as a result of this biography of the controversial tycoon. With some nostalgia I recall listening to BBC Radio 4’s World at One and hearing Sir Richard’s triumphant boast outside the Royal Palaces of Justice in Fleet Street after his libel victory against Guy Snowden, the chairman of Camelot, a rival bidder for the original lottery licence. ‘My mother taught me to always tell the truth,’ Branson told his excited audience.

This book was to cast an objective interpretation on his career just as his bid for the National Lottery was being reconsidered after a bitter court case. To Branson’s distress, the original decision to award him the lottery licence was overturned. Partly, he knew, this book’s revelations had turned opinion against him. Now, eight years later, Branson’s recent activities, self-promotion and solecisms, especially during his bid for the distressed bank Northern Rock, have warranted an updated version of the original book.

Over the past eight years I have occasionally been invited to write articles for newspapers about Branson. Each article automatically provokes Branson to complain about ‘multiple inaccuracies’ and demand the publication of his version of the truth. Invariably, identical facts provoke starkly different interpretations. My articles published during his bid for Northern Rock especially provoked his ire. I did not think that his controversial past justified the government’s original decision to entrust over £50 million of taxpayers’ money to the Virgin group. For whatever reason, the government finally agreed with me. The loss of Northern Rock could be as grave a blow to Branson’s fortunes as his failure to win the Lottery licence.

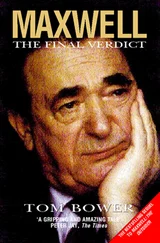

Sir Richard nevertheless remains one of the world’s most popular tycoons. Countless ambitious and intelligent young people, aspiring to become successful businessmen, voraciously read his autobiography and other publications in their attempts to understand the secret of his success. If they believe that his version is the Holy Grail, they are mistaken. During my own career following the lives of other tycoons including Robert Maxwell, Mohamed Fayed, Tiny Rowland, Geoffrey Robinson and Conrad Black, one common denominator has always emerged. An important element of their success has been the myths generated to conceal their aggressive journeys up the greasy pole. Similarly, once they bask in the spotlight, they share a brazen aggression to maintain their version of the ‘truth’ against those posing honest questions. However outstanding a personality Branson may be, he is weakened by his forceful attempts to silence his critics and his victims; and it is the latter, his hapless business partners, who remain frustrated by his remorseless success.

Eight years ago, Branson had reached a precipice, and his empire’s prosperity was endangered. Brilliantly, his juggling snatched victory from possible defeat. Now, once again, his fortunes are challenged. Whether he can stage another resurrection is a tantalising question. The Branson rollercoaster never stops.

Tom Bower

London, July 2008

In early June 1988, Ken Berry, a discreet director of the Virgin Group, arrived in Tokyo on a secret assignment. Berry, a deal-maker trusted by Richard Branson, was searching for $150 million.

Although Virgin Music was a publicly owned company, Richard Branson preferred not to reveal Berry’s mission to his British shareholders and his two non-executive directors.

Berry had arranged to meet Akira Ijichi, the president of Pony Canyon, a subsidiary of a giant Japanese media company. Their introduction at the Intercontinental Hotel in the Shinjuku district lasted two hours.

‘This meeting has got to remain secret,’ stipulated Berry. Ijichi nodded his agreement. Berry continued: ‘Virgin needs money to expand. We’re looking for $150 million.’ That was not the complete reason for Berry’s search for money.

Three months later, in September, Akira Ijichi arrived in London with his translator Moto Ariizumi, a junior executive in the company. Both stayed at the Halcyon Hotel, in Holland Park, conveniently close to Branson’s home. By then, their New York bankers had undertaken an external examination of the Virgin Group’s business and finances. Negotiations, the bankers had suggested, should start at $125 million for a 25 per cent stake.

Berry, a natural deal-maker, could sense Ijichi’s enthusiasm. The Japanese was flush with cash. During their discussions in Virgin’s offices on the Harrow Road, Berry emphasised on several occasions, ‘We don’t want any publicity. We don’t want the shareholders to know.’ The secrecy suited the Japanese: they wanted the deal to succeed.

Later, at the end of their second day in London, the two Japanese met Richard Branson for dinner at his home. Their host was charming but firm: ‘The company’s worth $600 million. Not a dollar less.’ Ijichi nodded.

The following morning, the two Japanese were welcomed by Branson on his houseboat in Little Venice. Amid the stripped pinewood floors, cane furniture and leafy plants Branson shone, in Moto Ariizumi’s opinion, as a ‘quite extraordinary but fashionable’ representative of the alternative culture.

Before their departure, Akira Ijichi agreed to pay $150 million for a 25 per cent stake although several important details remained unresolved. Branson and Berry were untroubled by the delay. In the meantime, Branson had dramatically announced his decision to privatise the Virgin Group. His unexpected decision to buy back the shares from the public had caused considerable surprise although everyone was grateful that he valued the Virgin Group at £248 million, double the stock market’s value. However, when Virgin’s shareholders met in November 1988 to formally approve Branson’s proposed privatisation, neither the shareholders nor Virgin’s two non-executive directors were aware of Berry’s continuing negotiations with the Japanese. If the shareholders had known about Pony Canyon’s agreement that the Virgin Group was worth $600 million, or £377 million – £129 million more than the sum offered to shareholders – they might have demanded that Branson buy back the shares at the same valuation.

Читать дальше