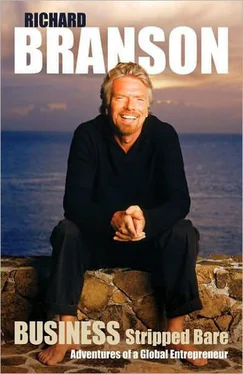

Richard Branson

BUSINESS STRIPPED BARE

Adventures of a Global Entrepreneur

I’d like to dedicate this book to

all the wonderful people — past and present —

who have made Virgin what it is today.

Writing Business Stripped Bare has been another life lesson for me. I’ve been able to remind myself of many of the business escapades that I’ve been involved in over the years. I know some of my Virgin colleagues are decidedly nervous about what I might be saying —and whether I might go ‘off message’, as the politicians say —but a real strength of the Virgin Group is that they are prepared to let me talk candidly about the business.

Of course, any lapses in memory about events are purely my own. What do they say at the end of television true-life dramas — that ‘some names and dates have been changed’? Not really necessary in this case, but my intention is not to embarrass or disparage anyone.

The Virgin story has been a phenomenon — building a global business in one lifetime — and it still has a long way to go. We have packed so much in. Over the years there have been so many outstanding and committed people steering our Virgin businesses. I really should thank them all individually but if I did, this book would be twice the size and the publishers wouldn’t be too happy with me. So I shall save my thanks for those who have had a direct influence on the business in recent years.

I’d like to acknowledge the work and assistance of Stephen Murphy, Virgin’s chief executive, who gets little credit for the magnificent job he does; Gordon McCallum, Mark Poole, Patrick McCall and Robert Samuelson; Jonathan Peachey and Frances Farrow in America; Andrew Black in Canada; Brett Godfrey in Australia; Dave Baxby in Asia-Pacific; and Jean Oelwang at Virgin Unite, our charitable enterprise. At Virgin Atlantic Airways, Steve Ridgway has been a great friend and confidant for many years, while Alex Tai at Virgin Galactic has shared a lot of adventures with me, and his colleague Stephen Attenborough is working hard on our exciting new space venture. Thanks to Tony Collins at Virgin Trains, Jayne-Anne Gadhia at Virgin Money and Matthew Bucknall at Virgin Active; to our legal team, led by Josh Bayliss, who have kept us on the straight and narrow path; to our PR gurus Nick Fox and Jackie McQuillan; to my perfectly formed personal team of Nicola Duguid and Helen Clarke, based here on Necker Island; and to Ian Pearson for looking after the Virgin Archives in Oxfordshire.

I’d like to thank Will Whitehorn, the president of Virgin Galactic, and a long-term adviser and friend, for steering this book project. At Virgin Books, now part of Random House, I’d like to thank Richard Cable, Ed Faulkner and Mary Instone for their hard work in defining the shape of the book. Thanks also to my good friends Andy Moore, Andy Swaine, Adrian Raynard, Holly Peppe and Gregory Roberts for their friendship and feedback.

I’d like to record my appreciation of journalist Kenny Kemp, my collaborator and researcher on this text, who chased me around the world and grabbed time away from my busy business schedule to help me with my thoughts, and Simon Ings who helped me to craft those thoughts so well.

And, finally, a wonderful thanks to my wife, Joan, my children, Holly and Sam, and my dearest mum and dad for all your love and support.

Richard Branson

Necker Island, August 2008

I spoke to him nearly every day, using him as a sounding board. He seemed to me the kind of business expert who could enhance our thinking. He gave us good advice on the Virgin One account. His name was Gordon McCallum. He used to work for the business consultancy McKinsey & Co., and I knew he’d been doing some work for Wells Fargo —to do with consumer banking and financial services and major retailers including JC Penney. I trusted him. I knew a lot about him —but it suddenly dawned on me one day: ‘Gordon? Do you work for us?’

‘Yes,’ he replied.

‘I mean, are you an employee?’

‘No, Richard, I’m not. I’m still working as a freelance consultant at the moment.’

Oh.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘you’d better come for a job interview. See you tomorrow at the house.’ And I put the phone down.

I can’t remember much about that night but I must have had fun; when Gordon turned up at my place in Holland Park, at 9 a.m. sharp, I was still in bed. In fact, I couldn’t seem to get out of it. So I tucked myself under the sheet and called him up and said: ‘Well, I’d like to offer you a full-time job.’

It was not the kind of meeting he had expected, but he rose to the challenge. ‘What kind of job?’

‘What kind of job would you like?’

Finally Gordon cracked. In all his years at McKinsey he had never come across this technique as a way of identifying corporate talent. He burst out laughing, but he wasn’t put off. ‘I’d like to help Virgin develop a much clearer business strategy for the brand and help you expand it further internationally.’

This made a lot of sense. It was what I’d been hoping for. ‘What would your title be?’ I said, and leaned over to grab my dressing gown.

He thought about it. ‘Something like Strategy Director?’

‘Fine — we’ll call you the Group Strategy Director of Virgin.’

We sorted out the money, and the deal was done — and I went off to have a shower.

Is this any way to do business?

Absolutely.

At its heart, business is not about formality, or winning, or ‘the bottom line’, or profit, or trade, or commerce, or any of the things the business books tell you it’s about. Business is what concerns us. If you care about something enough to do something about it, you’re in business, and you’ll find ideas in this book that will help you. This is a business book for everyone, whether or not they imagine themselves to be ‘business people’.

Making the most of Gordon’s considerable talents and playing fair by him was not a ‘business decision’ I had to make — it was simply my business, my concern, my affair. I’m no less a businessman when I’m in a dressing gown — and I’m certainly not more of one when I put on a suit.

This was brought home to me pretty sharply in July 2007, during an hour-long session at the Aspen Ideas Festival. I was being interviewed by Bob Schieffer, the former CBS news anchorman of the Evening News . This is the man who moderated the 2004 presidential election debate between George W. Bush and John Kerry. Bob knows his stuff, so I expected a grilling. He could see that underneath my brash exterior I still harbour some nervousness about speaking in public, so he started off warm and generous, getting me nice and relaxed, conversing about all kinds of matters from terrorist extremism to space tourism, before he delivered his sucker punch. I had left school at fifteen to set up a student magazine, and Bob asked me why I had gone into business .

I just stared at him. I suddenly realised I had never been interested in being ‘in business’. And, heaven help me, I said so, adding: ‘I’ve been interested in creating things.’

Now, feeble as that sounded on the stage at Aspen, that’s the gist of my thinking about business. It shouldn’t be something outside of yourself. It shouldn’t be something you can stand away from. And if it is, there’s something wrong.

Over the years, the Virgin Group has made it its business to run railways, build a spaceship, launch a new airline in Africa, and help fight Aids and HIV. These are our concerns. Not all of them are ‘businesses’ in the usual sense — and the journalists who have accused the Virgin Group of making no business sense are right, but in the wrong way. The greatest and most unusual achievement of the Virgin Group is that, unlike most businesses, it remembers what it’s for .

Читать дальше