Dedication

For Kennedy

Contents

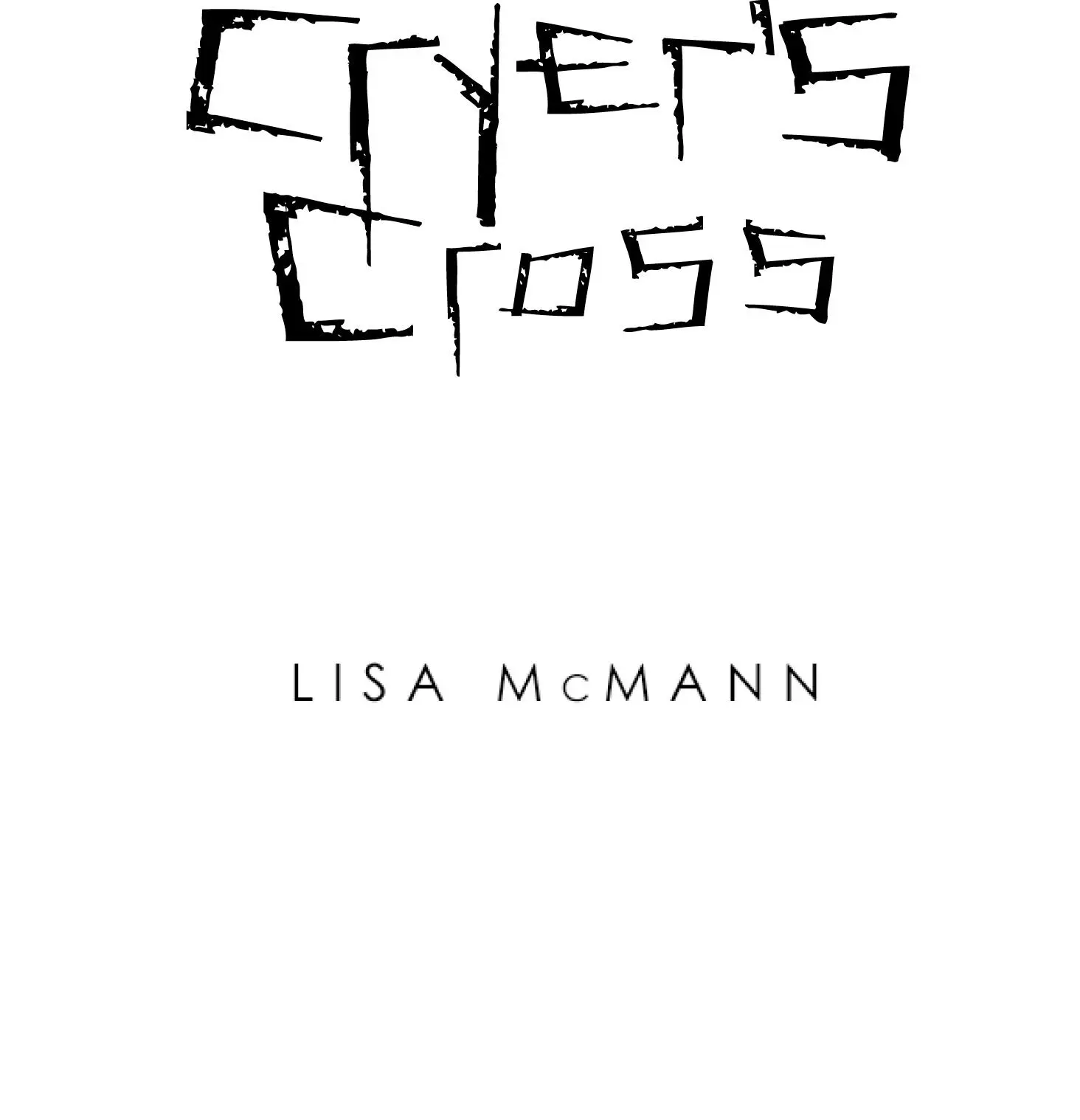

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Acknowledgments

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Everything changes when Tiffany Quinn disappears.

Of the 212 residents of Cryer’s Cross, Montana, 178 join Sheriff Greenwood in a search that lasts several days from sunup to after dark. School is closed, all the students taking part, searching roads and farms, trudging through pastures of cattle and horses, through sections of newly planted potatoes, barley, wheat. Up to the foothills and back along the woods. They travel in groups of two or three, some nervous, some crying, some resolute. Shouting to the other groups now and then so nobody else goes missing—cell phones aren’t much good out here. Cryer’s Cross is a dead spot.

After five days there is still no trace of Tiffany Quinn. She is gone, impossibly. Impossibly, because to imagine that there has been foul play here in the humble town of Cryer’s Cross is laughable, and to imagine that sweet ninth-grade bookworm running away, going off on her own . . . It’s all so impossible.

But gone she is.

Still, they search.

Kendall Fletcher flinches and casts regular glances behind her out of habit. Scared about the younger girl’s disappearance, true, but also unsettled by this shake-up in her schedule. The final week of her junior year canceled—everything left unfinished, open ended. Her whole routine is off.

She walks the hundreds of acres of her parents’ farm and beyond into the woods, wearily counting her steps through the potatoes and grain fields and trees. Counting, always counting something.

Her best friend, Nico Cruz, walks next to her.

Boyfriend, he’d say.

But boyfriend means commitment, and commitments that she can’t keep tend to make Kendall feel prickly. “Come on,” she says. “Let’s run.”

She takes off through the field, and Nico follows. They pass an imaginary soccer ball between the rows, occasionally yelling out “Tiffany!” Once, after they cross over to Nico’s family’s land, they see a big brown lump where the barley field meets the gravel road, but it’s not Tiffany. Just a road-killed deer.

She’s not here. She’s not anywhere.

They take a break under a tree at the edge of the farm as rain starts to fall. Kendall stares and counts the drops as they hit the gray dirt, faster and faster.

Nico talks, but Kendall isn’t listening. She needs to get to a hundred drops before she can allow herself to stop.

Eventually the search ends. Nothing more can be done locally except by professionals now. It’s prime planting season. Farmers have chores, and students do too. Plus jobs, if they work in town or for one of the farmers or ranchers. Life has to go on.

It’s a long, hot summer full of hard work for Kendall. For everyone. After a month or two, people stop talking about Tiffany Quinn.

In September when school starts again, Kendall arrives as she always does, the first one to the one-room high school, except for old Mr. Greenwood, the part-time janitor, who retreats to his basement hideout whenever students are around.

Kendall is tan and not quite freakishly tall. Athletic. Her long brown hair has natural highlights from her driving a tractor and working on the farm all summer.

There was too much time to think up there on that tractor, since all it takes is a GPS to run it up and down the rows. And when your brain has a glitch and its lap counter is broken, the same thoughts whir around on an endless loop. Tiffany Quinn. Tiffany Quinn. Tiffany Quinn.

Kendall imagines every possible scenario for Tiffany. Running away. Getting lost. Being abducted. Maybe even raped, murdered. Wondering which one really happened, and if they’ll ever know the truth. She pictures all of it happening to herself, and it almost makes her cry. Pictures Tiffany screaming for help, begging to live . . . Kendall’s eyes blur as she remembers her summer, turning the tractor through the fields and obsessing about such horrible things. It seemed so real, so scary, as if someone were about to jump out of the woods and attack her.

She knows some of her thoughts are irrational. She knows it and always has known it, even in fifth grade, when she used to layer on clothes—four shirts, three pairs of underwear, shorts under her jeans—anxiously, frantically, crying her eyes out for fear people could see her naked through her clothes. What an awful time that was. Fear like that is constant, tiring. But the psychologist over in Bozeman helped. Explained OCD—obsessive-compulsive disorder—and eventually that particular phase of worry went away, only to be replaced by other obsessions, other compulsions.

She’s not crazy. She just can’t stop thinking things when weird ideas get lodged in her head. She also can’t stop glancing behind her—it has become her latest compulsion. This whole thing with Tiffany has set her back some.

So she’s glad to be back at school, though feeling a little desperate because of how last year ended. And anxious to start this year fresh. Anxious to have new thoughts, new assignments bombard her brain, keep her mind occupied with non-scary things. Soccer practice starting up again. New DVD dance routines to learn. New things to keep her busy, body and mind. It’s a relief.

On this first day she tidies up the classroom in a way that old Mr. Greenwood doesn’t, turning the wastebasket so the dent is in the right place, straightening the markers on the dry-erase board and putting them in color order to match Roy G Biv as closely as possible, opening the curtains just so. Lining up the desks into their proper places in neat quadrants, one quadrant of six desks for each high school grade. Kendall creates aisles separating the quadrants to give the teacher room to walk between them, so she can address each grade individually rather than having all twenty-four desks together. It’s the way Kendall likes things.

Nobody’s ever complained.

Nobody even knows.

The desks are ancient and sturdy beasts from the 1950s, recycled by the state from who knows where. It’s a workout moving them all, but Kendall feels better when everything is back to normal. She sees where her old desk ended up, over in the freshman quadrant this year. Now the tenth graders will have an empty seat, unless the rumors are true. There’s a new family in town, according to Nico, though Kendall hasn’t seen anyone new around town yet. Kendall hopes they have a sophomore to fill the spot left by Tiffany, to make things in that section neat again. Though Tiffany coming back would be the best thing, of course. But Sheriff Greenwood and the local news anchors say that’s just not likely. Not after all this time has passed.

Читать дальше