I am most grateful to my colleagues who have read all or part of an earlier draft: the late Professor Leonard Schapiro, Peter Frank, Steve Smith, Bob Service and, the most tireless of my students, Philip Hills. At crucial stages of the writing, I have benefited from conversations with Mike Bowker, William Rosenberg and George Kolankiewicz. Where I have ignored their advice and gone my own way, I acknowledge full responsibility.

I am much beholden to the support and encouragement of my wife Anne, and my daughters Katherine and Janet. Without their endless patience and indulgence, this book would have been abandoned long ago, and then they might have seen more of me.

School of Slavonic Studies,

University of London,

July 1984

Preface to Second Edition

By a strange coincidence, the first edition of this book was published on the very day that Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. That made for good publicity, but it meant that the text rapidly became overtaken by the remarkable events which began to take place under the new leadership. It is true that in the last pages of the old edition I remarked that change, when it came, would be rapid and far-reaching, and that the Soviet public would prove to be more ready for it than we were then accustomed to think. As a pointer to the future, that now seems to have been reasonably apt, but all the same, a mere four years into the new era, a generous extension of the last chapter seemed essential to give some idea of the momentous changes which have been occurring and to relate them to earlier Soviet history. I have taken this opportunity to correct a few errors earlier in the text, and thank those reviewers and readers who have pointed them out to me.

School of Slavonic & East European Studies,

University of London,

July 1989

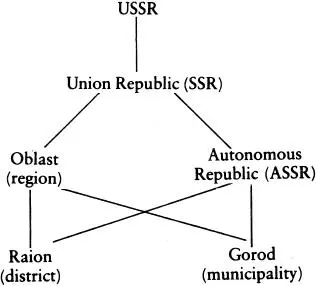

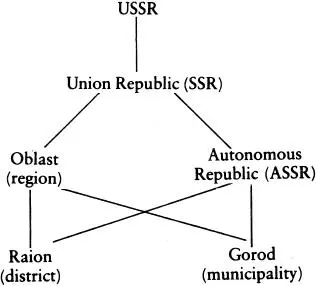

Often in the text I refer to one or other of the main administrative divisions of the Soviet Union. These may be schematically laid out as follows:

‘The philosophers have only explained the world; the point is to change it.’ This famous dictum of Marx invites us to judge his doctrine by its practical consequences, in other words by examining the kind of society which has resulted from its application. Yet, paradoxically, many Marxists themselves will deny the validity of such a judgement. They will dismiss the example of Soviet society as an unfortunate aberration, the outcome of a historical accident, by which the first socialist revolution took place in a country unsuited to socialism, in backward, autocratic Russia.

It is important, therefore, to begin by asking ourselves just why this happened. Was it indeed a historical accident? Or were there elements in Russia’s pre-revolutionary traditions which predisposed the country to accept the kind of rule which the followers of Marx were to impose?

It is true that Russia was, in some ways, backward and it was certainly autocratic. Economically speaking–in agriculture, commerce and industry–Russia had lagged behind Western Europe from the late Middle Ages onward, largely as a result of two centuries of relative isolation under Tatar rule. There is, however, no single track along which history advances, and this backwardness had positive as well as negative features. It made the mass of the people more adaptable, better able to survive in harsh circumstances. It may also have helped to preserve a more intimate sense of local community, in the peasants’ commune ( mir ) and the workmen’s cooperative ( artel ).

Politically, on the other hand, nineteenth-century Russia might be thought of as rather ‘advanced’, if by that we mean resembling twentieth-century Western European political systems. It was an increasingly centralized, bureaucratized and in many ways secular state; its hierarchy had strong meritocratic features; it devoted a considerable share of its resources to defence, and operated a system of universal male conscription; and it accepted an ever more interventionist role in the economy. Furthermore, the state’s opponents, the radicals and revolutionaries, pursued secular utopias with the same mixture of altruism, heroism and intense self-absorption which characterized, for example, the West German and Italian terrorists of the 1960s and 1970s. What Russia did not have, of course, was parliamentary democracy, though even that was developing, in embryonic form, from 1906.

As for autocracy, there were very good reasons why it should have proved the dominant political form in Russia, and why it should have been acceptable to most of the people. It is unnecessary to postulate an inborn ‘slave mentality’, as many Westerners are prone to do. First, there are Russia’s flat, open frontiers, which have been both her strength and her weakness. Her strength, because they gave Russia’s people the chance to spread eastwards, colonizing the whole of northern Asia and occupying in the end one-sixth of the earth’s surface. Her weakness, because they have rendered Russia ever vulnerable to attack, from the east, the south and, especially in recent centuries, from the west. For that reason all Russian governments have made the securing of their territory their chief priority, and have received the whole-hearted support of the population in so doing. National security has been, in fact, more than a priority–an obsession to which, when necessary, everything else has been sacrificed with the enthusiastic approval of the people. Any other people in such circumstances would react the same way. That is not to say that Russian governments have not abused the trust their subjects have placed in them: on the contrary they have found it possible to do so again and again. But the geographical and historical motives for accepting strong authority have nearly always prevailed.

Another reason for the popular identification with the autocrat is that, historically speaking, Russia’s formation as a self-conscious nation began unusually early. The Tatar occupation of the thirteenth century generated, by reaction, intense Russian national feeling, which centred on the Orthodox Church, as the one national institution which had survived the disaster. And because the church conducted its liturgy not in Latin but in a Slavonic tongue close to the vernacular, this national feeling had deep roots among the ordinary people. All this imparted to Russian national consciousness from early times a demotic quality, a defensiveness, and an earth-boundness which still have strong echoes today. Its religious basis was celebrated as soon as Russia was able, thanks to strong Muscovite rulers, to throw off the Tatar yoke. Moscow Grand Dukes proclaimed themselves Tsars (Caesars), claiming the heritage of Byzantium, which had fallen to the infidels in 1453: ‘Two Romes have fallen, the third Rome stands, and there shall be no fourth.’ Russia became Holy Russia, the one true Christian empire on earth.

In order to ensure that armies could be raised and the country defended, the tsars imposed a tight hierarchy of service on the whole population. Nobles were awarded land in the form of pomestya , or service estates, on condition that they performed civilian or military service, usually the latter. They also had to raise a unit of fighting men from among the peasants committed to their charge. In this way the old independent aristocrats, the boyars, were gradually displaced, while the peasants became enserfed, fixed to the land, bound to serve their lord, to pay taxes, and to provide recruits for the army. For nobles and peasants alike, their function and status in society was defined by state service. Society became almost an appendage to the state.

Читать дальше