GEOFFREY HOSKING

RUSSIA

PEOPLE AND EMPIRE

1552–1917

Cover

Title Page GEOFFREY HOSKING RUSSIA PEOPLE AND EMPIRE 1552–1917

Introduction

PART ONE The Russian Empire: How and Why?

PART TWO State-building

1 The First Crises of empire

2 The Secular State of Peter the Great

3 Assimilating Peter’s Heritage

4 The Apogee of the Secular State

PART THREE Social classes, religion and culture in Imperial Russia

1 The Nobility

2 The Army

3 The Peasantry

4 The Orthodox Church

5 Towns and the Missing Bourgeoisie

6 The Birth of the Intelligentsia

7 Literature as ‘Nation-Builder’

PART FOUR Imperial Russia under pressure

1 The Reforms of Alexander II

2 Russian Socialism

3 Russification

4 The Revolution of 1905–7

5 The Duma Monarchy

6 The Revolution of 1917

Conclusions

Afterthoughts on the Soviet Experience

Chronology

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

ALSO BY GEOFFREY HOSKING

RUSSIA PEOPLE AND EMPIRE

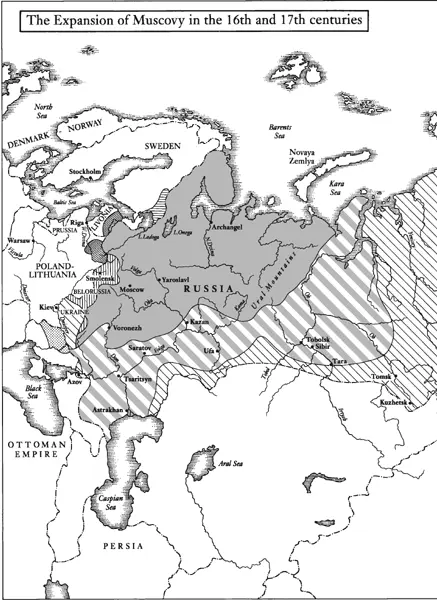

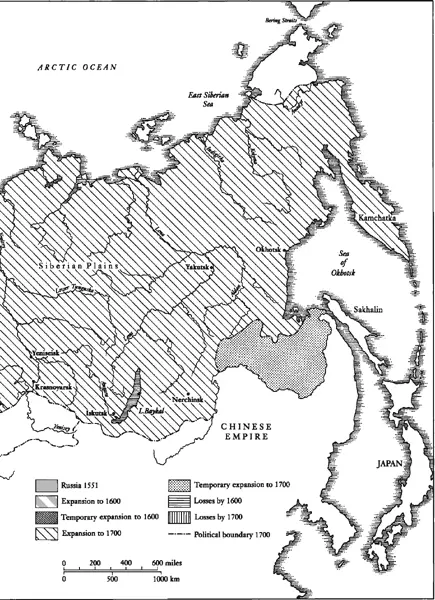

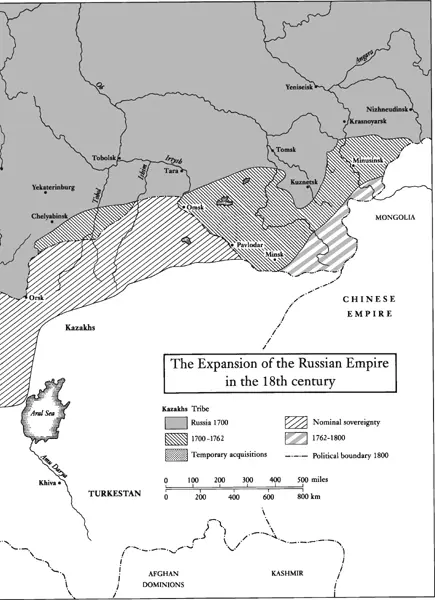

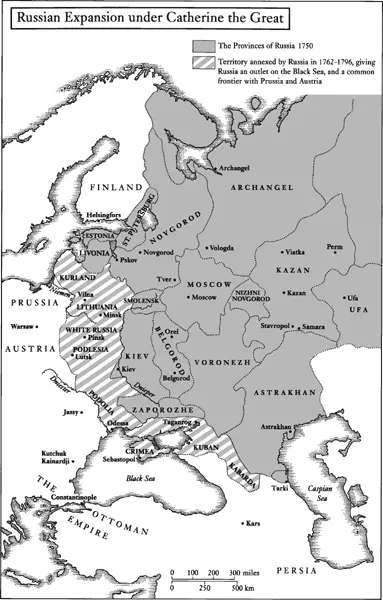

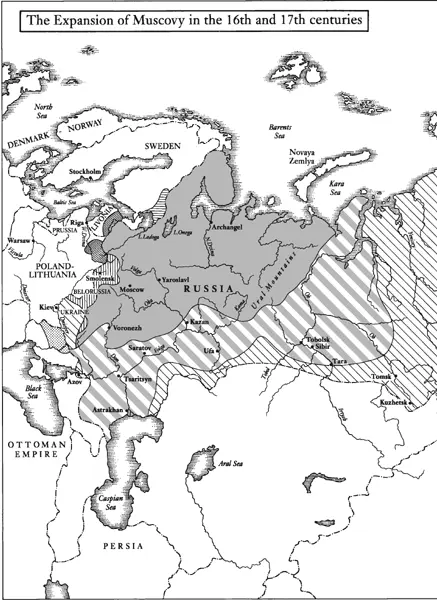

MAPS

Copyright

About the Publisher

Rus’ was the victim of Rossiia Georgii Gachev

If this book were in Russian, the title would contain two distinct epithets: russkii for the people and rossiiskii for the empire. The first derives from Ras’, the word customarily employed to denote the Kievan state and the Muscovite one in its early years. The second comes from Rossiia, a Latinized version probably first used in Poland, which penetrated to Muscovy in the sixteenth century and became common currency in the seventeenth – precisely during the time when the empire was being founded and extended. 1

In that way the Russian language reflects the fact that there are two kinds of Russianness, one connected with the people, the language and the pre-imperial principalities, the other with the territory, the multi-national empire, the European great power. Usage is not absolutely consistent, but any Russian will acknowledge that there is a considerable difference in tonality and association between the two words. Rus’ is humble, homely, sacred and definitely feminine (the poet Alexander Blok called her ‘my wife’); Rossiia grandiose, cosmopolitan, secular and, pace grammarians, masculine. The culturologist Georgii Gachev has dramatized the distinction: ‘Rossiia is the fate of Rus’. Rossiia is attraction, ideal and service – but also abyss and perdition. Rossiia uprooted the Russian people, enticed them away from Rus’, transformed the peasant into a soldier, an organiser, a boss, but no longer a husbandman.’ 2

The theme of this book is how Rossiia obstructed the flowering of Rus’, or if you prefer it, how the building of an empire impeded the formation of a nation. So my story concerns above all the Russians. There have been many books in recent years about the non-Russian peoples of the empire, and the problems of their national development. 3It is time to redress the balance in favour of the Russians, whose nationhood has probably been even more blighted by the empire which bore their name.

Russians, especially in the nineteenth century, have always believed that their distinctiveness – some saw it as their curse – derived from an underlying problem of national identity, but few western historians have taken the notion seriously, preferring to dismiss the Russian obsession with the national problem as an excuse for imperial domination or reactionary politics. I believe the Russians are right, and that a fractured and underdeveloped nationhood has been their principal historical burden in the last two centuries or so, continuing throughout the period of the Soviet Union and persisting beyond its fall. Such an assertion may surprise Russia’s neighbours, who are accustomed to regard Russian nationalism as overdeveloped and domineering. This is an understandable optical illusion, but an illusion nevertheless, as I shall try to demonstrate.

Social scientists have been reluctant to define the term ‘nation’, and indeed, whenever the attempt is made, there invariably turn out to be one or two anomalous ‘nations’ which do not fit the definition. I shall nevertheless try to pin the notion down. A nation, it seems to me, is a large, territorially extended and socially differentiated aggregate of people who share a sense of a common fate or of belonging together, which we call nationhood.

Nationhood has two main aspects. One is civic: a nation is a participating citizenry, participating in the sense of being involved in law-making, law-adjudication and government, through elected central and local assemblies, through courts and tribunals, and also as members of political parties, interest groups, voluntary associations and other institutions of civil society. The second aspect of nationhood is ethnic: a nation is a community bound together by sharing a common language, culture, traditions, history, economy and territory. In some nations, for historical reasons, one aspect predominates over the other: the French, Swiss and American nations are primarily ‘civic’, while the German and East European nations have tended to emphasize ethnicity. 4I believe that both aspects of Russians’ nationhood have been gravely impaired by the way in which their empire evolved.

Would it have been better for Russians if they had been able to form a nation? I believe it would have made their evolution less unstable, polarized and violent, especially during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The nation-state has proved to be the most effective political unit during that time, not only in Europe but throughout the world, because it is the largest one compatible with creating and sustaining a feeling of community and solidarity, such as induces loyalty and reduces the need for coercion. National identity plays an important compensatory role in a period when the operations of the market have tended to break down older, smaller and simpler forms of social solidarity. In an era of large-scale warfare it is even more crucial, as Charles Tilly has commented:

Читать дальше