‘When digging into the soil of the North China plain or northern Chekiang [Zhejiang], centres of Chinese civilisation from the earliest times onward,’ remarked Erik Zurcher in the 1950s, ‘it is actually difficult not to find anything’. 7Zurcher was writing about the spread of Buddhism in the fourth and fifth centuries AD. Adherents of the new faith evidently had an uncanny knack of unearthing Buddhist relics in Chinese soil just when opponents were deploring the Indian, and so non-Chinese, origins of their faith. Such finds, besides supposedly authenticating Buddhism’s long association with China, were considered highly auspicious. Just as the fall of an imperial dynasty was usually accompanied by a series of depressing portents – floods, drought, locusts, etc. – so the rise of a new dynasty was heralded by a rash of favourable omens, none more so than the excavation of some hoary artefact. Since antiquity itself was so highly regarded, the discovery of, say, a Bronze Age urn clearly signified Heaven’s approval of whatever new dispensation laid claim to its discovery.

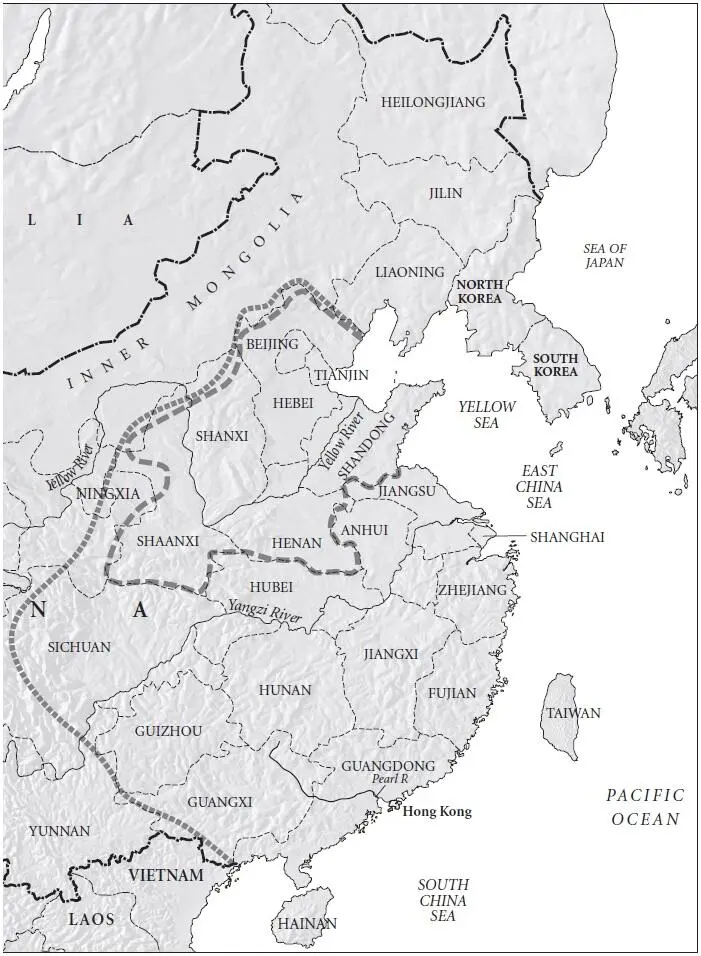

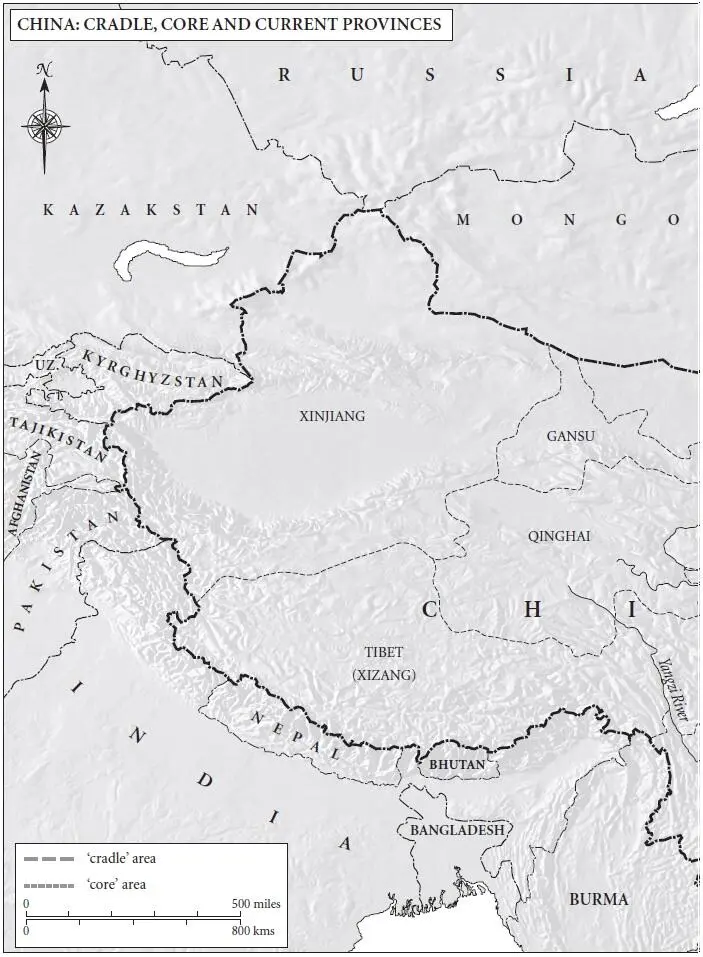

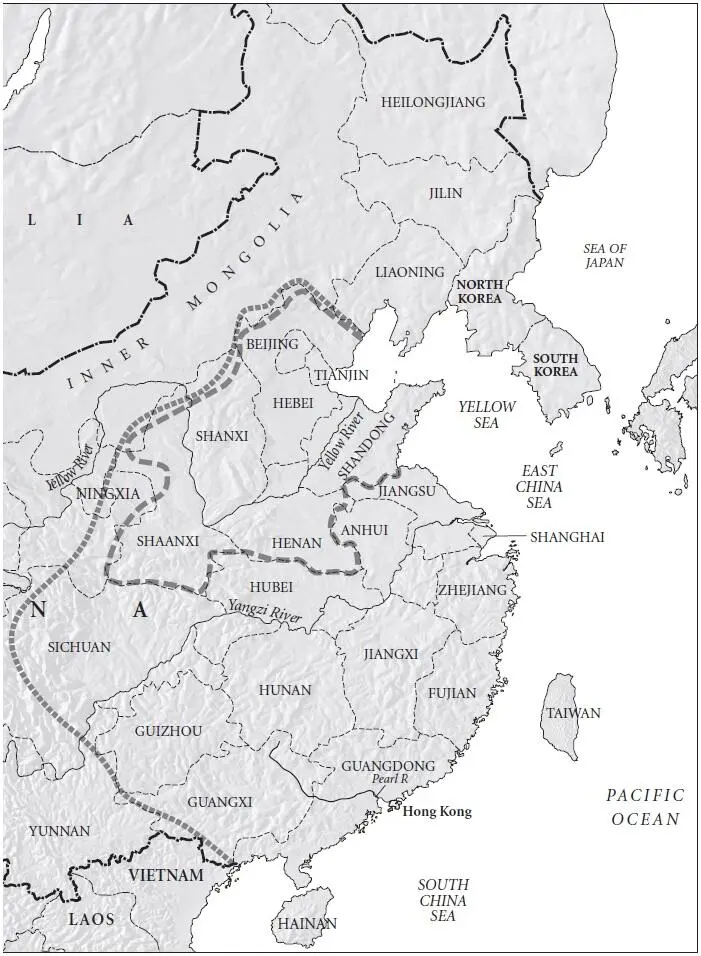

Something of the same thinking may have influenced Chinese archaeology in the mid-twentieth century. The Nationalist revival had its own need of historical legitimisation, and so did the Republic of China, declared in 1912, and the People’s Republic, in 1949. Scholars and officials brought up on the Standard Histories of the historiographical tradition and now fired by the spirit of national reassertion knew to look for the origins of Chinese civilisation in the north of the country. Resources were duly directed there and, as noted by Zurcher, diggers in that region could hardly fail to be rewarded. To general delight, the spadework yielded ample corroboration of the authenticity and antiquity of an ancient Chinese civilisation in the northern provinces, especially the Yellow River (Huang He) basin, which corresponded to that described in the earliest texts and histories. Only incorrigible sceptics, mostly from outside China, wondered whether devoting as much archaeological attention and resources to other parts of China, such as the Yangzi basin or the south, might not yield comparable finds that would necessarily qualify this northern bias in early Chinese history.

Such doubts have since been vindicated. By the end of the twentieth century the expansion in archaeological activity compared well with the exponential growth being enjoyed by the economy. Indeed, the two were related. Funds were now available for more widespread excavation, and because so much of the Chinese landscape was being torn up anyway for construction projects, the finds came thick and fast. On the other hand, their study and conservation acquired still greater urgency. Mechanical excavators might unearth in minutes what spadework might not turn up in years, and just as quickly they might destroy it.

A typical example was provided by a 1970s hospital extension at Mawangdui on the outskirts of Changsha, capital of the southern province of Hunan. Construction of the hospital’s new ward ‘accidentally disturbed’ an adjacent mound that archaeologists had earmarked for attention back in the 1950s. 8The matter was reported to the provincial authorities, and when orders were issued for immediate excavation, a swarm of Mao-suited archaeologists descended on the site and duly reclaimed one of the greatest hoards of modern times. There were three immense tombs dating from the second century BC, and each contained a nest of monumental coffins, within one of which were found a well-preserved female corpse and the oldest silk paintings and maps ever to have been discovered in China. Also recovered were texts containing early versions of some of the Chinese classics and enough artefacts, apparel, insignia, lacquerware, jades, weapons and other grave goods to justify the construction of Changsha’s grand new museum – and then fill it. In 1983 another mound, this time in the middle of Guangzhou (Canton), the capital of neighbouring Guangdong province, yielded magnificent tombs of similar period that prompted presentation of the site itself as an imaginative museum within walking distance of the city’s main railway station. Elsewhere in Guangzhou, site clearance for the erection of a plaza has lately revealed a 2,000-year-old wooden watergate. The oldest in the world and now comfortably encased within the gleaming new plaza, it may be reached by taking the elevator down to floor B1.

Opulent finds like these located far from the supposed epicentre of ancient Chinese civilisation in the Yellow River basin call for radical revision of received ideas about what the rest of China was like before, and immediately after, the birth of Christ. But with more new discoveries being reported every week, no such bold reappraisal has yet been presented. The Cambridge History of Ancient China , published in 1999, frankly admitted defeat. Unable to reconcile the literary sources with these new ‘material’ sources – or unable to find a contributor prepared to have a go – the editors compromised by commissioning parallel chapters for the same periods, one based on textual sources and the next on archaeological sources. Sometimes they support one another, sometimes not. Early Chinese history still awaits a convincing rewrite.

While making but a modest contribution on this front, the present work is designed to meet the much more pressing need for an overall history of China that does not take for granted a foreknowledge of the subject or an acquaintance with the Chinese language. A glance at the existing literature in English suggests an international consensus, not to say conspiracy, to make the subject as daunting and incomprehensible as possible. This state of affairs, in part a legacy of competitive scholarship in the colonial era, will be fearlessly addressed; for China’s history is long enough and its culture challenging enough without gratuitous complication. Confronting this challenge may mean taxing the reader, but not, it is earnestly hoped, without rewarding his or her effort.

As lamentable as the obfuscations are the depths of ignorance from which foreigners approach Chinese history. Most people could name half a dozen Roman emperors but few could name a single Chinese emperor. Confronted with an array of Chinese proper names in their Romanised spellings, English-speakers experience a recognition problem, like a selective form of dyslexia, that makes the names all seem the same. Unfamiliarity lies at the root of the problem, particularly in respect of Chinese geography, chronology and translation conventions. It can best be overcome by diligence and long exposure, but at the risk of irritating those already superior to such difficulties, what follows (and the accompanying tabulations) may help as an introduction.

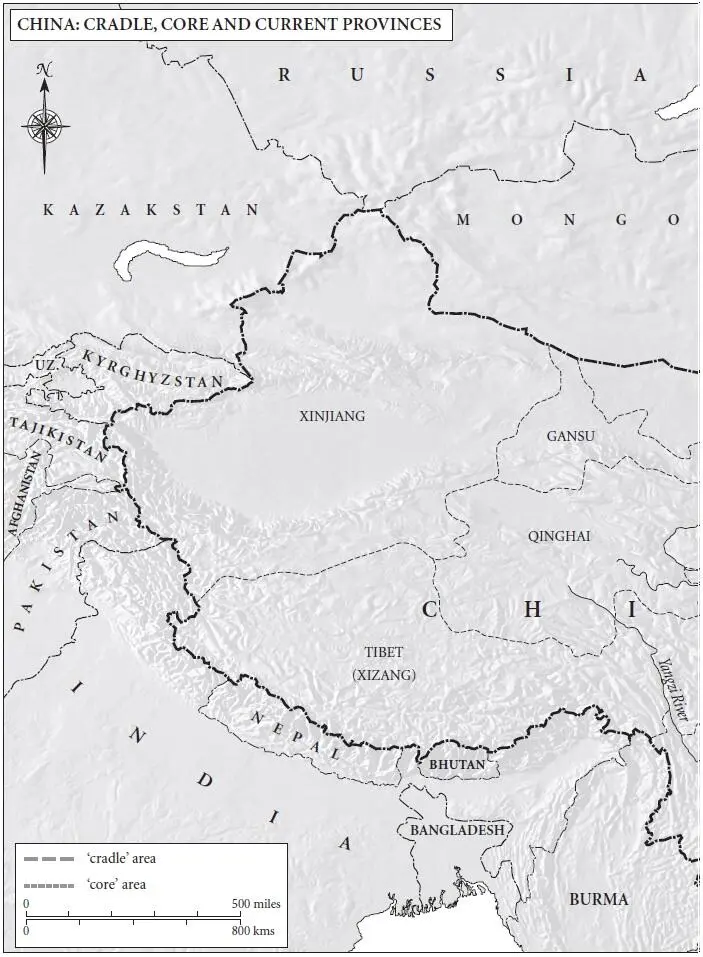

For administrative purposes China is today divided into twenty-eight provinces. A few of these provinces are of quite recent provenance, and in all cases the areas they denote have undergone change. But most have a long pedigree, and it is not therefore unreasonable to employ the provincial terminology retrospectively so as to provide a geographical framework for the whole spread of Chinese history.

Fortunately the names of the provinces often contain helpful clues as to their whereabouts. Bei , dong , nan and xi are Romanised renderings of the Chinese words for ‘north’, ‘east’, ‘south’ and ‘west’, and shan is ‘mountain’. Shandong (‘Mountain-east’, once spelled ‘Shantung’) is therefore the province with a rugged peninsula below Beijing. It originally extended inland as far as the north–south Taihang mountains; hence ‘east of the mountains’ or ‘Mountain-east’. By the same dazzling logic, Shanxi province (‘Mountain-west’) is its counterpart to the west of the Taihang range.

Читать дальше