This placed the order in a position to organise annual forays ( reysas ) against the pagans for kings, princes and knights who wished to acquit themselves of the duty to bear arms for Christ. These reysas were like safaris for the visiting grandees, who not only fulfilled their crusading vows but enjoyed a good campaign. They also took away a favourable impression of the order, which they subsequently expressed by giving it grants of land in their own countries and by supporting it diplomatically. At the same time, the increase in crusading activity in the region created tensions and problems of its own, as it was now drawing in not only Denmark, Sweden, Norway and the Polish duchies, but also the emerging state of Lithuania and the Russian principalities of Novgorod and Muscovy.

By 1283 most of Prussia had been conquered. Although it was settled by a considerable number of landless Polish and German knights, it was the Teutonic Order that ruled the province. It established a formidable stronghold at Marienburg, a number of castles throughout the territory and a port at Elbing (Elbląg) to carry trade from the province. It proved an efficient administrator, as monastic discipline precluded venality and its structure provided a degree of continuity which dynastic states (with their disputed successions, minorities and likelihood of feckless or incompetent rulers) lacked. The knights’ rule was relatively benign to begin with. They favoured voluntary over forced conversion of the autochton—ous population, and were pragmatic enough to use local pagans to fight alongside them when necessary. But repeated revolts and apostasies made them take a more jaundiced view with time, and the autochtones were gradually all but exterminated.

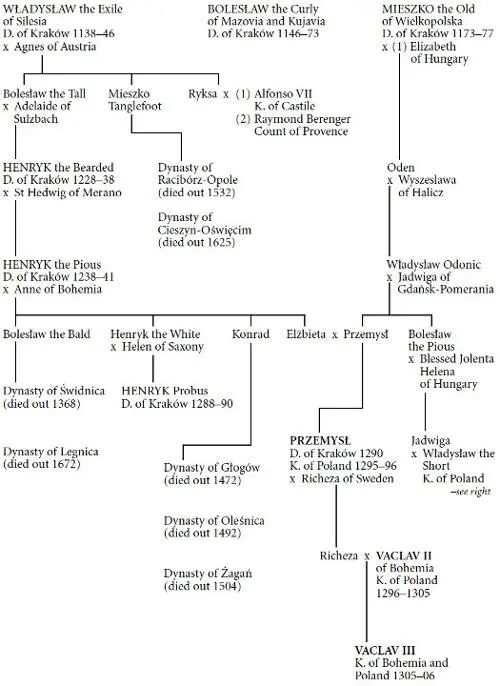

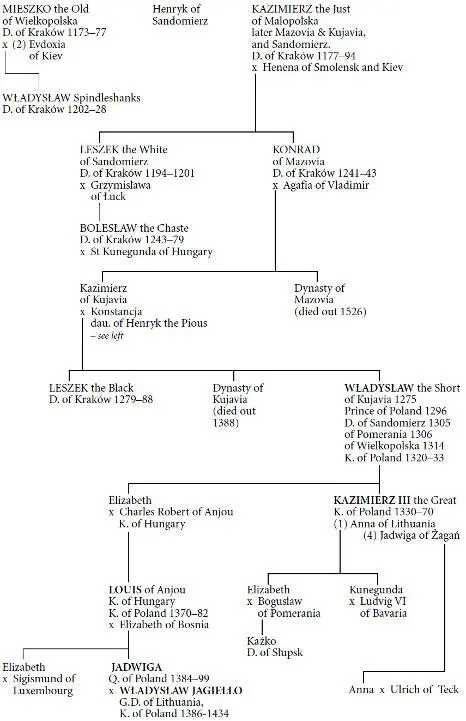

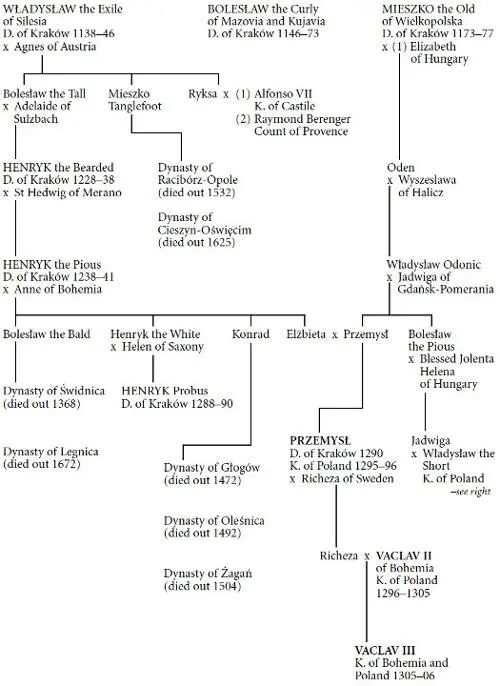

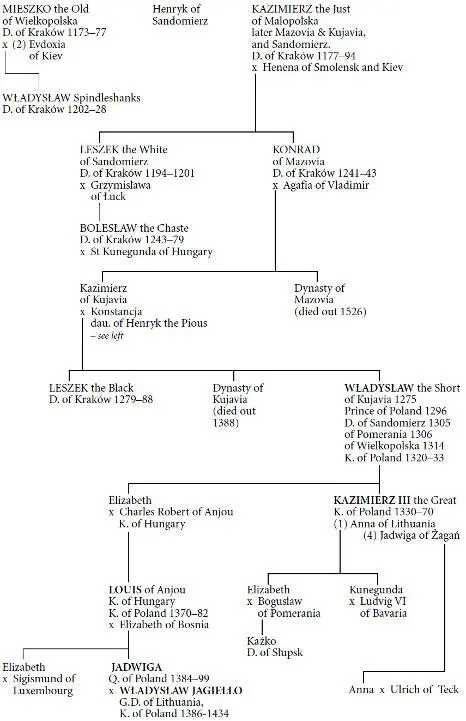

Fig. 2 The division and reunification of Poland under the later Piasts

In the space of fifty years, the Prussian nuisance on the Mazovian border had been replaced by a well-ordered state. This did not in itself represent a threat to the Polish duchies. But it was one of a series of developments that would.

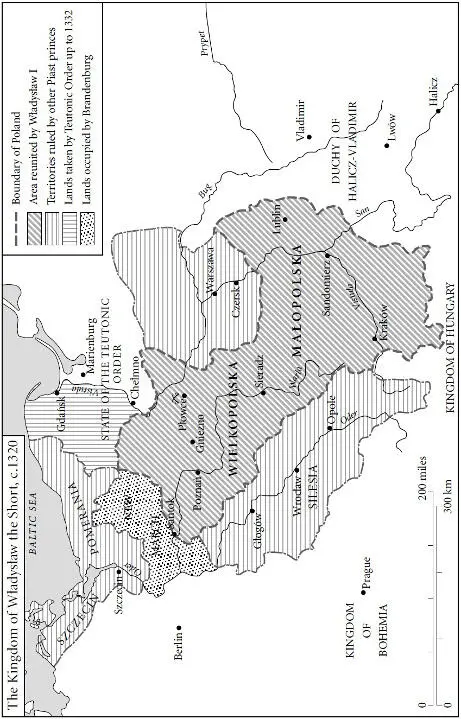

A century earlier, in 1150, the last Slav prince of Brenna died, to be succeeded by a German. The March of Brandenburg, as it then became, encroached eastwards, driving a wedge between Slav states on the Baltic, where the outflanked Prince Bogusław of Szczecin was forced to accept German overlordship, and those to the south, like the small principality of Lubusz, which was annexed to Brandenburg outright. In 1266 Brandenburg took Santok, and in 1271 Gdańsk, thus extending its own territory to that of the Teutonic Order. The Poles retook both Gdańsk and Santok in the following year, but they would never push the German advance back to the river Oder. From the stronghold they had set up at Berlin on the river Spree in 1231, the margraves of Brandenburg looked eastward, and they would seize every opportunity to extend their dominion in that direction.

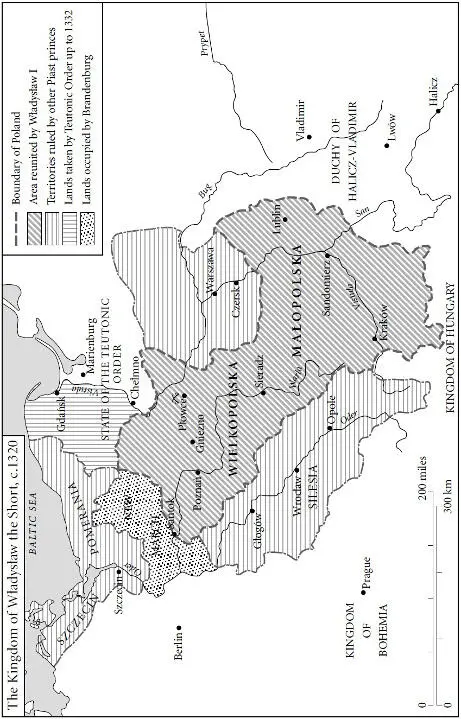

At the same time, settlers from all over Germany came in search of land and opportunity, usually well received by Polish rulers, and by the end of the thirteenth century not only Silesian and Pomeranian cities such as Wrocław and Szczecin, but even the capital, Kraków, had become predominantly German. In Silesia and Pomerania, the influx of landless knights and farmers from Germany also made itself felt in rural areas, radically affecting the will as well as the ability of local Piast rulers to stand by a disunited Poland. Like so many small shopkeepers, these minor rulers had to pay tribute to whoever was strong enough to impose protection. One by one the princes of Pomerania, outflanked by German states and undermined by the German ascendancy in their cities, particularly Hanseatic centres such as Szczecin and Stargard, had to accept the German Emperor instead of the Duke of Kraków as their overlord. This process weakened the greater Polish duchies as well, as a result of which even their independence came under threat. In 1300 King Vaclav II of Bohemia was able to invade Wielkopolska, and with the blessing of the Emperor have himself crowned King of Poland.

If the experience of the Tatar invasions had provided a powerful argument in favour of reuniting the Polish duchies into a single kingdom, this was given added weight by increasing resentment of the encroaching Germans and foreigners in general. After Bohemia’s capture of Kraków with the connivance of some of the townspeople in 1311, the Polish troops which retook it the following year rounded up all the citizens and beheaded those who could not pronounce the Polish tongue-twisters they were made to repeat.

It was also supported by the Church. Until now, this had not played a political role, merely an administrative one. Under the early Piast kings, the bishops had been little more than functionaries with no power-base of their own. The devolution of the country into separate duchies changed this, as the individual dukes needed the support of their local bishops. These were quick to perceive that if the Polish duchies were absorbed into Bohemia or Germany, the Polish Church would lose its autonomous status, and they took steps to counter the creeping Germanisation. At the Synod of Łęczyca in 1285 the Polish bishops adopted a resolution that only Poles could be appointed as teachers in church schools.

After the canonisation of Stanisław, the Bishop of Kraków put to death by Bolesław II and recognised as patron of Poland in 1253, the monk Wincenty of Kielce wrote a life of the saint in which the alleged miraculous growing together of his quartered body is described as prophetic of the way in which the divided Poland would become one again. Similarly patriotic sentiments can be detected in the chronicle of another Bishop of Kraków, Wincenty Kadłubek, written in the first years of the thirteenth century, and in the more reliable Kronika Wielkopolska , written by a churchman in Poznań in the 1280s.

The message was taken up by some of the dukes, who decided to abandon the hereditary principle and to elect from their number an overlord who would rule effectively in Kraków. Henryk Probus of Silesia was the first to be chosen in this way, and on his death in 1290 the Kraków throne was given to Przemysł II of Gniezno, who was actually crowned King of Poland in 1295, but was assassinated two years later by agents of Brandenburg. He was succeeded in 1296 by a prince of the Mazovian line, Władysław the Short, who was to become one of the most remarkable of Polish kings.

The Bohemian invasion of 1300 forced Władysław to flee the country for a time, and he went to Rome in search of allies. As his sobriquet suggests, he was a small man, but he knew what he wanted and how to get it, laying his plans with skill. The Papacy was locked in one of its perennial conflicts with the Empire, and therefore looked kindly on the anti-Imperial Polish prince. Władysław sought the support of Charles Robert of Anjou, the erstwhile King of Naples and Sicily who had just succeeded to the Hungarian throne. With the Pope’s support he sealed an alliance by marrying his daughter to the Angevin. Having also secured the cooperation of the princes of Halicz and Vladimir he set off to reconquer his realm from the Czechs.

In 1306 he took Kraków and in 1314 Gniezno, thus gaining control of the two principal provinces, while a third, Mazovia, recognised his overlordship. In 1320 he was crowned King of Poland, the first to be crowned at Kraków. By making an alliance with Sweden, Denmark and the Pomeranian principalities, Władysław forced Brandenburg on to the defensive while he dealt with the Teutonic Order, which was in a difficult position. The fall of Acre to the Saracens in 1291 had deprived it of its headquarters. The indictment in 1307 of the Templars, on whom the Teutonic Knights were closely modelled, their subsequent dissolution and savage persecution, were a chilling warning to any order which grew too powerful. Władysław lost little time in taking the Teutonic Order to a Papal court not only on charges of invasion and rapine, but on more fundamental questions of whether it was fulfilling its mission. The Papal judgement went against the order, but the very fact that the Knights had been cornered brought about a subtle change in their attitude.

Читать дальше