Since there was no framework of vassalage there were no natural channels for the exercise of central authority. Royal control therefore depended not on a local vassal as elsewhere in Europe, but on a functionary appointed by the king. He was known by his function, and his title of Castellan ( Kasztelan ) derived from the royal castle from which he exercised judicial, administrative and military authority on the king’s behalf. There were over a hundred of these castellans administering the Polish lands by 1250, but their importance waned along with central authority when the country was divided. In terms of power, they began to be superseded by the ministers of the individual dukes, the Palatines ( Wojewoda ).

This divergence from European norms is significant. Unlike Bohemia, which had faced similar challenges and choices, Poland had not been fully absorbed into the framework of European states. One consequence of this was that it remained more backward. But it maintained a greater degree of independence. And while it was divided into duchies it remained more uniform and cohesive as a society than many others, because it was not subjected to the mixed overlordships that placed large tracts of geographical France under the sovereignty of the king of England, areas of Germany under that of the French dynasty, or Italy at the mercy of a succession of Norman, French and German warlords. It was probably this that ensured the survival of Poland as a political unit.

TWO Between East and West

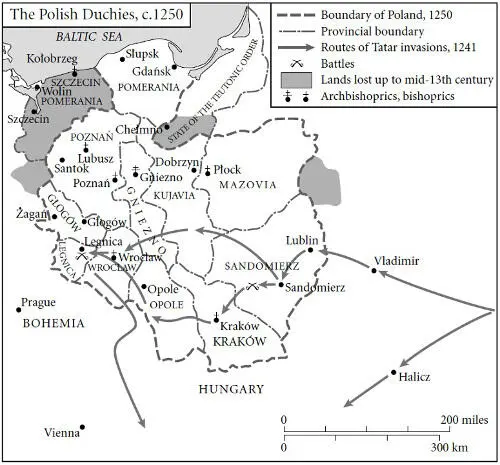

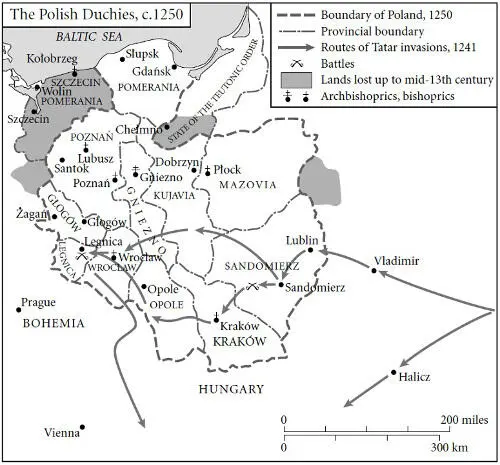

In 1241 the horde of the legendary Genghis Khan, now commanded by his grandson Batu, broke over eastern Europe in a great wave. It overran and put to fire and sword the principalities of southern Russia and then divided into two. The larger force swept into Hungary, the other ravaged Poland. The knighthood of Małopolska gathered to face it at Chmielnik, but were swamped and massacred. The Duke of Kraków, Bolesław the Chaste, fled south to Moravia.

The Tatars sacked Kraków, then rode on westwards into Silesia. Here Duke Henryk the Pious had massed all his own forces, as well as those of Wielkopolska, a contingent of foreign knights, and even the miners from his goldmines of Złotoryja. On 8 April 1241 he led them out of the city of Legnica to face the oncoming Tatars. His forces were defeated and Duke Henryk himself was hacked to pieces.

Happily for western Europe, the Tatars veered south to rejoin their brothers in Hungary and there news reached them of the death of their Khan Ugedey. They abandoned their westward advance and rode back whence they had come. Although they never again attempted a conquest of Europe, they would keep the whole of Russia under their yoke for the next three centuries and continued to harass Poland. In 1259 they sacked Lublin, Sandomierz, Bytom and Kraków. They returned in 1287, wreaking similar devastation. The horror of these raids was vividly captured in chronicle, legend and song, and is kept alive to this day in the hourly trumpet-call from the tower of St Mary’s Church in Kraków, which breaks off in the middle to commemorate the Tatar arrow that cut short the medieval trumpeter’s call. And it established the barbaric eastern infidel as a bogeyman in the Polish political mind.

The Tatar incursions showed up the vulnerability of a country divided. Although there was a community of interest, there had been no coordination of action, and regional militias were defeated one by one. Just as the Tatar threat died away, this vulnerability was beginning to be demonstrated on the other side of the country, where the other great bogeyman of modern Polish history was born, swaddled in steel marked with the black cross.

At a time when Poland had already been a Christian state for two hundred years, much of the southern and eastern Baltic coastline was still inhabited by pagans and was the scene of a fierce struggle carried on by Denmark, the Scandinavian kingdoms, Brandenburg and the Polish Dukes of Gdańsk-Pomerania and of Mazovia. Denmark, Brandenburg and other German princes vied with each other to conquer the area which would be known as Mecklenburg, with its valuable port of Liubice (Lübeck). Further east, where the Baltic coast curves northwards, the Danes and Scandinavians were making inroads into the lands of the Lithuanians, the Latvians, Lettigalians and Semigalians, and the Curonians. In between, the Poles battled against the Prussians, another Baltic people. The motives were the desire for land and trade, thinly disguised as missionary by local bishops who could not afford to have the Church excluded. This changed when St Bernard of Clairvaux started preaching the crusade all over Europe.

It was he who persuaded Pope Alexander III to use north European crusaders in northern Europe rather than the Middle East, and to issue, in 1171, a bull granting the same dispensations and indulgences to those who fought against the heathen Slavs or Prussians as to those fighting the Saracens. The advantage of a crusade was that any local duke who launched what was in effect a private war against his enemies could, by making an arrangement with his bishop, recruit foreign knights who would come and fight for him as unpaid soldiers. And the fruits of this crusade whetted the appetites of Danes, Poles and Germans alike. Although the first northern crusade was a failure, the heathen Slavs in Western Pomerania were gradually subjugated by the Germans and the Danes over the next fifty years.

Throughout the early 1200s the Dukes of Mazovia made inroads into Prussia, but this only provoked counter-raids from the Prussians. A methodical military takeover of the area was needed, and the only armies which could take up such a challenge were the military orders, the most famous of which, the Templars and Hospitallers, had proved their efficacy in Palestine. The Bishop of Riga had, in 1202, formed the Knighthood of Christ, better known as the Sword Brothers, to help him conquer and evangel—ise the Latvians. With the approval of Duke Konrad of Mazovia, the Bishop of Prussia followed suit by founding Christ’s Knights of Dobrzyn as the regular army of the Polish ‘mission’ to Prussia. But this was too small to cope with the task.

A more radical solution was called for, and so, in 1226, Konrad of Mazovia took a step whose consequences for Poland and for Europe were to be incalculable. He invited the Teutonic Order of the Hospital of St Mary in Jerusalem, known as the Teutonic Knights, to establish a commandery at Chełmno and help him con—quer Prussia. The Teutonic Knights, founded at Acre in Palestine on the model of the Templars, were attracted by the idea of a mission nearer home. They thought they had found one in Hungary, where they were given the task of holding the Tatars at bay, but King Andrew II of Hungary grew wary of their ambitions and shortly expelled them.

They could see the advantages of the Polish offer, but this time the Grand Master Hermann von Salza was determined to guarantee their future. He obtained documents from the Emperor Frederick II and a bull from Pope Gregory IX authorising the order to conquer Prussia and thereafter to hold it in perpetuity as a papal fief. Before he realised what he had let himself in for, Konrad of Mazovia discovered that the lease he had granted the order on the territory of Chełmno had become a freehold.

Hermann von Salza, who still kept his sights on the Holy Land, originally saw the Prussian theatre of operations as a sideshow. He despatched a few knights there in 1229, and a further contingent took part in a crusade into Prussia in 1232-33, preached by the Dominicans, in which several Polish dukes, the margraves of Meissen and Brandenburg, the Duke of Austria and the King of Bohemia took part, along with hundreds of German knights. The order’s involvement grew when, in 1237, it took over the Sword Brothers. And it was encouraged to take a greater interest in the area by successive Popes, whose wish to see the conversion of the pagan Balts was complemented by a desire to bring as much of northern Russia as possible into the fold of the Roman Church.

Читать дальше