HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.tolkien.co.uk

www.tolkienestate.com

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2018

All texts and materials by J.R.R. Tolkien © The Tolkien Estate Limited 2018

Preface, Notes and all other materials © C.R. Tolkien 2018

Illustrations © Alan Lee 2018

®, TOLKIEN ®and FALL OF GONDOLIN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

®, TOLKIEN ®and FALL OF GONDOLIN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

The Proprietor on behalf of the Author and the Editor hereby assert their respective moral rights to be identified as the author of the Work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008302757

Ebook Edition © August 2018 ISBN: 9780008302788

Version: 2018-09-20

To my family

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Plates

Preface

List of Illustrations

Prologue

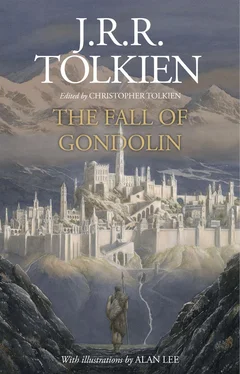

THE FALL OF GONDOLIN

The Original Tale

The Earliest Text

Turlin and the Exiles of Gondolin

The Story Told in the Sketch of the Mythology

The Story Told in the Quenta Noldorinwa

The Last Version

The Evolution of the Story

Conclusion

The Conclusion of the Sketch of the Mythology

The Conclusion of the Quenta Noldorinwa

Footnotes

List of Names

Additional Notes

Glossary

Map of Beleriand

The House of Bëor

The Princes of the Noldor

Works by J.R.R. Tolkien

About the Publisher

Swanhaven

‘They attempt to seize the swan-ships in Swanhaven, and a fight ensues’ (p.32)

Turgon Strengthens the Watch

‘he caused the watch and ward to be thrice strengthened at all points’ (p.64)

The King’s Tower Falls

‘the tower leapt into a flame and in a stab of fire it fell’ (p.96)

Glorfindel and the Balrog

‘that Balrog that was with the rearward foe leapt with great might on certain lofty rocks’ (p.107)

The Rainbow Cleft

‘he should be led to a river-course that flowed underground through which a turbulent water ran at last into the western sea’ (p.135)

Mount Taras

‘he saw a line of great hills that barred his way, marching westward until they ended in a tall mountain’ (p.160)

Ulmo Appears Before Tuor

‘Then there was a noise of thunder, and lightning flared over the sea’ (p.167)

Orfalch Echor

‘Tuor saw that the way was barred by a great wall built across the ravine’ (p.195)

In my preface to Beren and Lúthien I remarked that ‘in my ninety-third year this is (presumptively) the last book in the long series of editions of my father’s writings’. I used the word ‘presumptively’ because at that time I thought hazily of treating in the same way as Beren and Lúthien the third of my father’s ‘Great Tales’, The Fall of Gondolin . But I thought this very improbable, and I ‘presumed’ therefore that Beren and Lúthien would be my last. The presumption proved wrong, however, and I must now say that ‘in my ninety-fourth year The Fall of Gondolin is (indubitably) the last’.

In this book one sees, from the complex narrative of many strands in various texts, how Middle-earth moved towards the end of the First Age, and how my father’s perception of this history that he had conceived unfolded through long years until at last, in what was to be its finest form, it foundered.

The story of Middle-earth in the Elder Days was always a shifting structure. My History of that age, so long and complex as it is, owes its length and complexity to this endless welling up: a new portrayal, a new motive, a new name, above all new associations. My father, as the Maker, ponders the large history, and as he writes he becomes aware of a new element that has entered the story. I will illustrate this by a very brief but notable example, which may stand for many. An essential feature of the story of the Fall of Gondolin was the journey that the Man, Tuor, undertook with his companion Voronwë to find the Hidden Elvish City of Gondolin. My father told of this very briefly in the original Tale, without any noteworthy event, indeed no event at all; but in the final version, in which the journey was much elaborated, one morning out in the wilderness they heard a cry in the woods. We might almost say, ‘he’ heard a cry in the woods, sudden and unexpected. 1A tall man clothed in black and holding a long black sword then appeared and came towards them, calling out a name as if he were searching for one who was lost. But without any speech he passed them by.

Tuor and Voronwë knew nothing to explain this extraordinary sight; but the Maker of the history knows very well who he was. He was none other than the far-famed Túrin Turambar, who was the first cousin of Tuor, and he was fleeing from the ruin – unknown to Tuor and Voronwë – of the city of Nargothrond. Here is a breath of one of the great stories of Middle-earth. Túrin’s flight from Nargothrond is told in The Children of Húrin (my edition, pp.180–1), but with no mention of this meeting, unknown to either of those kinsmen, and never repeated.

To illustrate the transformations that took place as time passed nothing is more striking than the portrayal of the god Ulmo as originally seen, sitting among the reeds and making music at twilight by the river Sirion, but many years later the lord of all the waters of the world rises out of the great storm of the sea at Vinyamar. Ulmo does indeed stand at the centre of the great myth. With Valinor largely opposed to him, the great God nonetheless mysteriously achieves his end.

Looking back over my work, now concluded after some forty years, I believe that my underlying purpose was at least in part to try to give more prominence to the nature of ‘The Silmarillion’ and its vital existence in relation to The Lord of the Rings – thinking of it rather as the First Age of my father’s world of Middle-earth and Valinor.

There was indeed The Silmarillion that I published in 1977, but this was composed, one might even say ‘contrived’ to produce narrative coherence, many years after The Lord of the Rings. It could seem ‘isolated’, as it were, this large work in a lofty style, supposedly descending from a very remote past, with little of the power and immediacy of The Lord of the Rings. This was no doubt inescapable, in the form in which I undertook it, for the narrative of the First Age was of a radically different literary and imaginative nature. Nevertheless, I knew that long before, when The Lord of the Rings was finished but well before its publication, my father had expressed a deep wish and conviction that the First Age and the Third Age (the world of The Lord of the Rings ) should be treated, and published , as elements, or parts, of the same work .

Читать дальше

®, TOLKIEN ®and FALL OF GONDOLIN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

®, TOLKIEN ®and FALL OF GONDOLIN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited