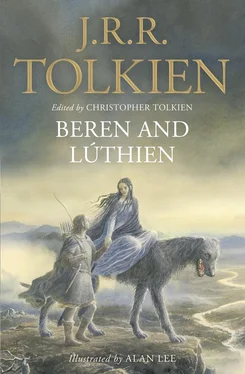

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.tolkien.co.uk

www.tolkienestate.com

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2017

All texts and materials by J.R.R. Tolkien © The Tolkien Estate Limited 2017

Preface, Notes and all other materials © C.R. Tolkien 2017

Illustrations © Alan Lee 2017

®, TOLKIEN ®and BEREN AND LÚTHIEN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

®, TOLKIEN ®and BEREN AND LÚTHIEN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

The Proprietor on behalf of the Author and the Editor hereby assert their respective moral rights to be identified as the author of the Work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008214227

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008214210

Version: 2018-03-29

For Baillie

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Plates

Preface

Notes on the Elder Days

BEREN AND LÚTHIEN

The Tale of Tinúviel

A Passage from the ‘Sketch of the Mythology’

A Passage Extracted from The Lay of Leithian

The Quenta Noldorinwa

A Passage Extracted from the Quenta

A Second Extract from The Lay of Leithian

A Further Extract from the Quenta

The Narrative in The Lay of Leithian to Its Termination

The Quenta Silmarillion

The Return of Beren and Lúthien According to the Quenta Noldorinwa

Extract from the Lost Tale of the Nauglafring

The Morning and Evening Star

Appendix: Revisions to The Lay of Leithian

Footnotes

List of Names

Glossary

Works by J.R.R. Tolkien

About the Publisher

‘yet now did he see Tinúviel dancing in the twilight’

‘but Tevildo caught sight of her where she was perched’

‘no leaves they had, but ravens dark / sat thick as leaves on bough and bark’

‘Now ringed about with wolves they stand, / and fear their doom.’

‘Then the brothers rode off, but shot back at Huan treacherously’

‘On the bridge of woe / in mantle wrapped at dead of night / she sat and sang’

‘now down there swooped / Thorondor the King of Eagles, stooped’

‘fluttering before his eyes, she wound / a mazy-wingéd dance’

“Surely that is a Silmaril that shines now in the West?”

After the publication of The Silmarillion in 1977 I spent several years investigating the earlier history of the work, and writing a book which I called The History of The Silmarillion. Later this became the (somewhat shortened) basis of the earlier volumes of The History of Middle-earth.

In 1981 I wrote at length to Rayner Unwin, the chairman of Allen and Unwin, giving him an account of what I had been, and was still, doing. At that time, as I informed him, the book was 1,968 pages long and sixteen and a half inches across, and obviously not for publication. I said to him: ‘If and/or when you see this book, you will perceive immediately why I have said that it is in no conceivable way publishable. The textual and other discussions are far too detailed and minute; the size of it is (and will become progressively more so) prohibitive. It is done partly for my own satisfaction in getting things right, and because I wanted to know how the whole conception did in reality evolve from the earliest origins …

‘If there is a future for such enquiries, I want to make as sure as I can that any later research into JRRT’s “literary history” is not turned into a nonsense by mistaking the actual course of its evolution. The chaos and intrinsic difficulty of many of the papers (the layer upon layer of changes in a single manuscript page, the vital clues on scattered scraps found anywhere in the archive, the texts written on the backs of other works, the disordering and separation of manuscripts, the near or total illegibility in places, is simply inexaggerable …

‘In theory, I could produce a lot of books out of the History , and there are many possibilities and combinations of possibilities. For example, I could do “Beren”, with the original Lost Tale fn1, The Lay of Leithian , and an essay on the development of the legend. My preference, if it came to anything so positive, would probably be for the treating of one legend as a developing entity, rather than to give all the Lost Tales at one go; but the difficulties of exposition in detail would in such a case be great, because one would have to explain so often what was happening elsewhere, in other unpublished writings.’

I said that I would enjoy writing a book called ‘Beren’ on the lines I suggested: but ‘the problem would be its organisation, so that the matter was comprehensible without the editor becoming overpowering.’

When I wrote this I meant what I said about publication: I had no thought of its possibility, other than my idea of selecting a single legend ‘as a developing entity’. I seem now to have done precisely that – though with no thought of what I had said in my letter to Rayner Unwin thirty-five years ago: I had altogether forgotten it, until I came on it by chance when this book was all but completed.

There is however a substantial difference between it and my original idea, which is a difference of context. Since then, a large part of the immense store of manuscripts pertaining to the First Age, or Elder Days, has been published, in close and detailed editions: chiefly in volumes of The History of Middle-earth. The idea of a book devoted to the evolving story of ‘Beren’ that I ventured to mention to Rayner Unwin as a possible publication would have brought to light much hitherto unknown and unavailable writing. But this book does not offer a single page of original and unpublished work. What then is the need, now, for such a book?

I will attempt to provide an (inevitably complex) answer, or several answers. In the first place, an aspect of those editions was the presentation of the texts in a way that adequately displayed my father’s apparently eccentric mode of composition (often in fact imposed by external pressures), and so to discover the sequence of stages in the development of a narrative, and to justify my interpretation of the evidence.

At the same time, the First Age in The History of Middle-earth was in those books conceived as a history in two senses. It was indeed a history – a chronicle of lives and events in Middle-earth; but it was also a history of the changing literary conceptions in the passing years; and therefore the story of Beren and Lúthien is spread over many years and several books. Moreover, since that story became entangled with the slowly evolving ‘Silmarillion’, and ultimately an essential part of it, its developments are recorded in successive manu-scripts primarily concerned with the whole history of the Elder Days.

Читать дальше

®, TOLKIEN ®and BEREN AND LÚTHIEN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

®, TOLKIEN ®and BEREN AND LÚTHIEN ®are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited