Lastly, I have arranged the content of the book in a manner distinct from that in Beren and Lúthien. The texts of the Tale appear first, in succession and with little or no commentary. An account of the evolution of the story then follows, with a discussion of my father’s profoundly saddening abandonment of the last version of the Tale at the moment when Tuor passed through the Last Gate of Gondolin.

I will end by repeating what I wrote nearly forty years ago.

It is the remarkable fact that the only full account that my father ever wrote of the story of Tuor’s sojourn in Gondolin, his union with Idril Celebrindal, the birth of Eärendel, the treachery of Maeglin, the sack of the city, and the escape of the fugitives – a story that was a central element in his imagination of the First Age – was the narrative composed in his youth.

Gondolin and Nargothrond were each made once, and not remade. They remained powerful sources and images – the more powerful, perhaps, because never remade, and never remade, perhaps, because so powerful.

Though he set out to remake Gondolin he never reached the city again: after climbing the endless slope of the Orfalch Echor and passing through the long line of heraldic gates he paused with Tuor at the vision of Gondolin amid the plain, and never recrossed Tumladen.

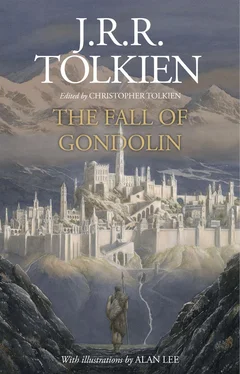

The publication ‘in its own history’ of the third and last of the Great Tales is the occasion for me to write a few words in honour of the work of Alan Lee, who has illustrated each Tale in turn. He has brought to this task a deep perception of the inner nature of scene and event that he has chosen from the great range of the Elder Days.

Thus, he has seen, and shown, in The Children of Húrin , the captive Húrin, chained to a stone chair on Thangorodrim, listening to Morgoth’s terrible curse. He has seen, and shown, in Beren and Lúthien , the last of Fëanor’s sons seated motionless on their horses and gazing at the new star in the western sky, which is the Silmaril, for which so many lives had been taken. And in The Fall of Gondolin he has stood beside Tuor and with him marvelled at the sight of the Hidden City, for which he has journeyed so far.

Finally, I am very grateful to Chris Smith of HarperCollins for the exceptional help that he has given to me in the preparation of the detail of the book, especially in his assiduous accuracy, drawing on his knowledge both of the demands of publication and the nature of the book. To my wife Baillie also: without her unwavering support during the long time the book has been in the making it would never have been made. I would also thank all those who generously wrote to me when it appeared that Beren and Lúthien was to be my last book.

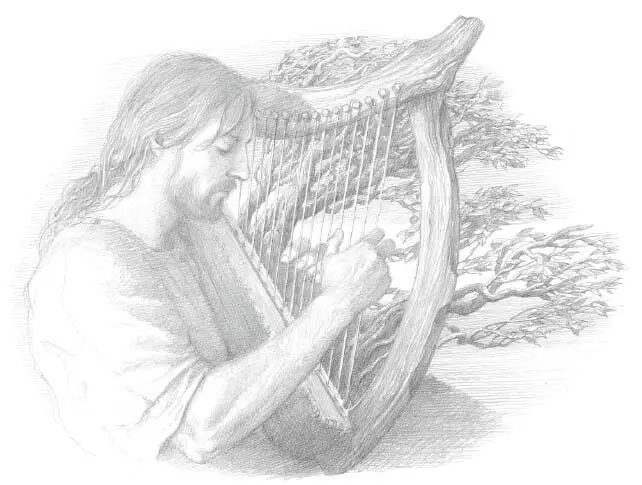

Tuor strikes a note on his harp

Tuor descends into the hidden river

Isfin and Eöl

Lake Mithrim

The mountains and the sea

Eagles fly above the encircling mountains

The delta of the River Sirion

Carved figurehead of Glorfindel in front of Elven-ships

Rían searches the Hill of Slain

The entrance to the King’s house

Tuor follows the swans to Vinyamar

Gondolin amid the snow

The Palace of Ecthelion

Elwing receives the survivors of Gondolin

Eärendel’s heraldic symbol above the sea

At the end of the book there will be found a map, and genealogies of the House of Bëor and the princes of the Noldor. These are taken from The Children of Húrin , with some minor alterations.

The black and white illustrations in this ebook are a true representation of how they appear in the print edition.

PROLOGUE

I will begin this book by returning to the quotation that I used to open Beren and Lúthien : a letter written by my father in 1964, in which he said that ‘out of my head’ he wrote The Fall of Gondolin ‘during sick-leave from the army in 1917’, and the original version of Beren and Lúthien in the same year.

There is some doubt about the year, arising from other references made by my father. In a letter of June 1955 he wrote ‘ The Fall of Gondolin (and the birth of Eärendil) was written in hospital and on leave after surviving the Battle of the Somme in 1916’; and in a letter to W.H. Auden of the same year he dated it to ‘sick-leave at the end of 1916’. The earliest reference of his that I know of was in a letter to me of 30 April 1944, commiserating with me on my experiences of that time. ‘I first began’ (he said) ‘to write The History of the Gnomes 1in army huts, crowded, filled with the noise of gramophones’. This does not sound like sick-leave: but it may be that he began the writing before he went on leave.

Very important, however, in the context of this book, was what he said of The Fall of Gondolin in his letter to W.H. Auden of 1955: it was ‘the first real story of this imaginary world.’

My father’s treatment of the original text of The Fall of Gondolin was unlike that of The Tale of Tinúviel , where he erased the first, pencilled manuscript and wrote a new version in its place. In this case he did indeed extensively revise the first draft of the Tale, but rather than erase it he wrote a revised text in ink on the pencilled original, increasing the multiplicity of change as he progressed. It can be seen from passages where the underlying text is legible that he was following the first version fairly closely.

On this basis my mother made a fair copy, notably exact in view of the difficulties now presented by the text. Subsequently my father made many changes to this copy, by no means all at the same time. Since it is not my purpose in this book to enter into the textual complexities that all but invariably accompany the study of his works, the text that I give here is my mother’s, including the changes made to it.

It must however be mentioned in this connection that many of the changes to the original text had been made before my father, in the spring of 1920, read the Tale to the Essay Club of Exeter College at Oxford. In his introductory and apologetic words, explaining his choice of this work in place of an ‘Essay’, he said of it: ‘It has of course never seen the light before. A complete cycle of events in an Elfinesse of my own imagining has for some time past grown up (rather, has been constructed) in my mind. Some of the episodes have been scribbled down. This tale is not the best of them, but it is the only one that has so far been revised at all and that, insufficient as that revision has been, I dare read aloud.’

The original title of the tale was Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin , but my father always later called it The Fall of Gondolin , and I have done the same. In the manuscript the title is followed by the words ‘which bringeth in the Great Tale of Eärendel’. The teller of the tale in the Lonely Isle, on which see Beren and Lúthien here– here, was Littleheart (Ilfiniol), son of that Bronweg (Voronwë) who plays an important part in the Tale.

It is in the nature of this, the third of the ‘Great Tales’ of the Elder Days, that the massive change in the world of Gods and Elves that had taken place should bear upon the immediate narrative of the Fall of Gondolin – and is indeed a part of it. A brief account of those events is needed; and rather than write one myself I think it far better to use my father’s own condensed, and characteristic, work. This is found in the ‘Original Silmarillion ’ (also ‘ A Sketch of the Mythology ’), as he himself called it, which can be dated to 1926, and subsequently revised. I used this work in Beren and Lúthien , and again in this book as an element in the evolution of the tale of The Fall of Gondolin ; but I use it here for the purpose of providing a concise account of the history before Gondolin came into being: it also has the advantage of itself deriving from a very early period.

Читать дальше