Certain details in this book, including names, places and dates, have been changed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2015

FIRST EDITION

© Jo Hardy and Caro Handley 2015

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Cover images © Sarah Tanat-Jones (animal illustrations); Johnny Ring (photograph)

Cover layout © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2015

Jo Hardy asserts the moral right to be

identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008142483

Ebook Edition © November 2015 ISBN: 9780008142490

Version: 2015-09-24

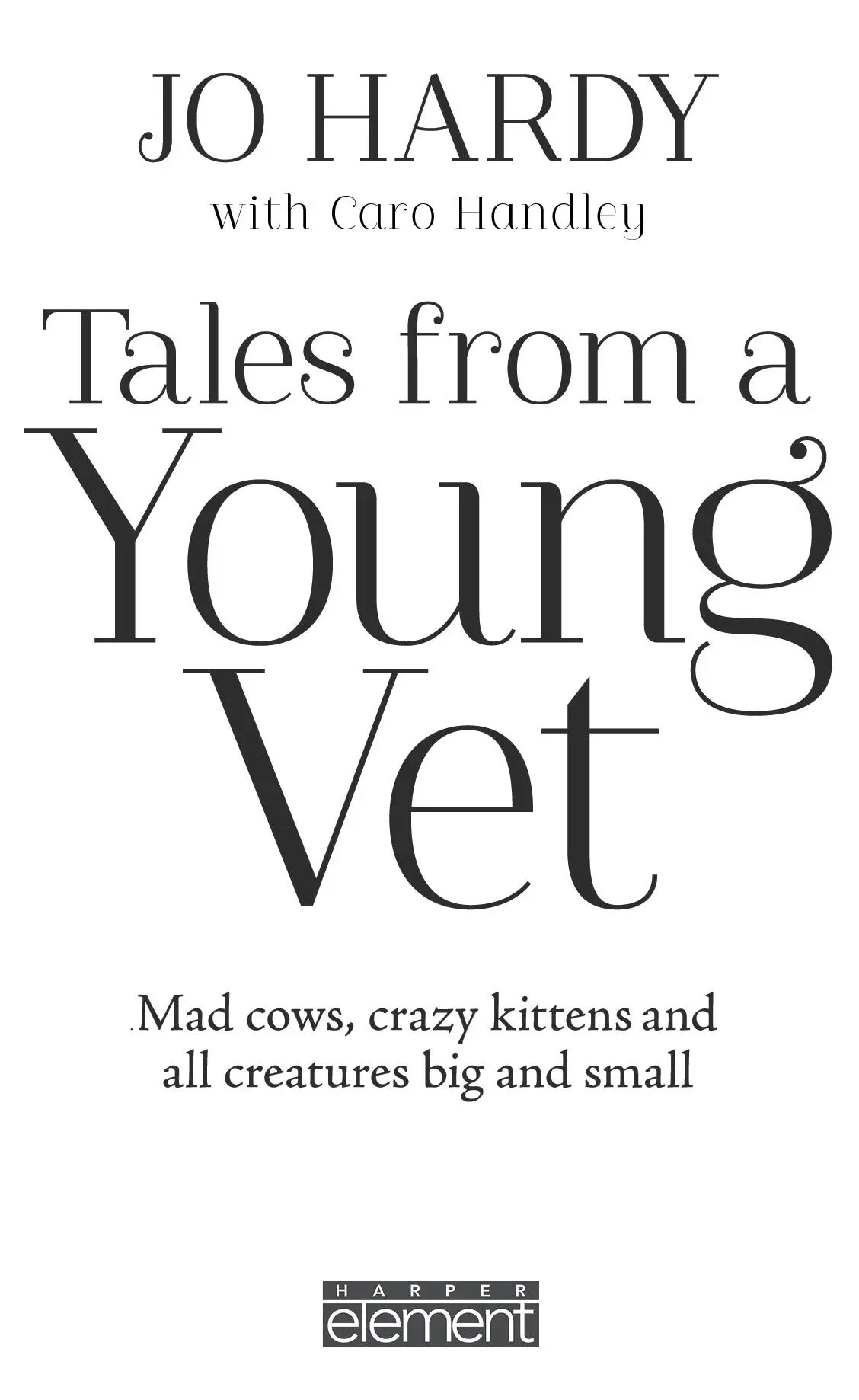

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One: Critical Care and the Night Shift

Chapter Two: Black Monday

Chapter Three: The Vaccine Trick and Dermaholiday

Chapter Four: ‘Don’t Cry, Englishman’

Chapter Five: ‘What Seems to Be the Problem?’

Chapter Six: For the Love of Horses

Chapter Seven: Fly on the Wall

Chapter Eight: We Saved a Life

Chapter Nine: Into the Wild

Chapter Ten: Between Two Worlds

Chapter Eleven: The Kitten who Thought She Was a Parrot

Chapter Twelve: Mad Cows and Doris the Goat

Chapter Thirteen: ‘Happy Christmas, Clunky’

Chapter Fourteen: Grumpy Lizards and Misty-eyed Gorillas

Chapter Fifteen: Stella the Heifer

Chapter Sixteen: Man’s Best Friend

Chapter Seventeen: Horse Sense

Chapter Eighteen: Luca the Great Dane

Chapter Nineteen: The End in Sight

Acknowledgements

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

Critical Care and the Night Shift

‘Can you help her? Please? She means the world to me. I don’t know what I’d do without Misty.’

Tears filled the eyes of the elderly woman on the other side of the consultation table as she looked down at the small white ball of fur in her arms.

I took a deep breath.

‘Pop her on the table and let’s have a quick look.’

Misty was a little terrier, and she was clearly feeling pretty ill. She lay on her side on the table in front of me, whimpering and panting frantically. Terriers can be real rascals, full of energy, always keeping their owners on their toes, but poor Misty was obviously in a bad way.

I was doing my best to sound confident, but inside I was quaking. It was my first twelve-hour shift in Emergency Critical Care – the equivalent of accident and emergency for pets – at the world-famous Queen Mother Hospital for Animals, and it was my job to assess each new case as it came in and to judge whether the animal could wait for attention or needed to be rushed straight to the Emergency Room – or ER – for treatment.

This was crunch time. As a fourth-year vet student I’d done all the theory, attended endless lectures, written papers and taken exams; in fact, just about everything except take charge of real live animals. Now, I, together with the other 250 students in my year at the Royal Veterinary College, was starting the final year of training – a whirlwind of back-to-back work placements known as rotations in which we’d be taking all that we’d learned in the classroom and putting it to the test in practices, farms, zoos and animal hospitals. We’d be covering everything from surgery to radiology to anaesthesia and tackling a whole range of life-saving procedures for the first time. Each of our three dozen or so placements would be assessed – we couldn’t afford to fail a single one.

I’d started out feeling a mixture of excitement and terror, anticipation and blind panic. What if I blew it, made a wrong diagnosis, failed to spot something vital or just froze? Was I really cut out to be a vet, or had I been fooling myself? It was time to find out. So here I was, in Emergency Critical Care, just three weeks into rotations, in at the deep end, dealing with a non-stop queue of very sick animals with very worried owners and having to make the vital first-stage triage assessments on my own.

That morning I’d got my kit ready – the unwritten vet ‘uniform’ of chinos, flat pumps and checked shirt. Over that went the student’s purple scrub top with my name stitched onto the top left side, plus a stethoscope round my neck, thermometer, scissors, notepad and pens (lots) shoved in my pockets. And a fob watch, because as vets we had to keep our arms below the elbow bare of clothing or jewellery.

Knowing that I’d be on the front line of emergency animal care had kept me awake for a good part of the night. So far we’d had a couple of easy weeks, learning how to take diagnostic images and spending time in dermatology. But now, along with the four other trainee vets in my rotation group, I would be facing a continuous stream of animals, all needing a split-second diagnosis. Animals can’t tell you what they’re feeling, so all a vet can do is look at the presenting symptoms, the animal’s condition and its history and put everything together to try to work out what’s going on.

I looked down at Misty, trying to remember my list of vital checks and questions. A three-year-old West Highland terrier, she was clearly in distress. Her temperature was high and her heart was racing. Her face looked swollen and her breathing was becoming ever more laboured.

Her owner, Mrs Stevens, was clearly worried and distressed. I could see that Misty meant the world to her. In a shaky voice she explained that she had taken Misty to the park a few hours earlier.

‘It was such a nice day,’ she said, her voice wobbling with emotion. ‘The sun was out, so we went for a walk and stopped for a bit. I sat on a bench and Misty was chasing around in the flowerbed. Then she yelped. I think she might have been stung by a bee. But surely that wouldn’t make her so ill, would it?’

She had just given me the clue I needed. I was pretty sure it had to be anaphylactic shock – an extreme allergic reaction – and there wasn’t much time to waste. The swelling was now so intense that Misty’s tongue and gums were turning blue from lack of oxygen.

‘I think Misty may have had a bad reaction to that sting,’ I told her. ‘Sometimes it can be very extreme. I’ll need to take her through to see a senior vet. Try not to worry. You have a sit down and I’ll ask someone to bring you a cup of tea.’

‘Please do your best,’ she said, her eyes filling again. ‘I can’t lose her.’

I carried Misty through to the treatment room, where I explained to the clinician in charge what I thought was going on. He agreed, and the team swung into action to administer oxygen via a mask, IV fluids and steroids. The steroids would reduce the inflammation in her mouth and larynx so that she could breathe properly again. A nurse ran to get a fan to bring down her temperature, which was still rising. As the team rushed around Misty I checked her vital signs – heart rate, respiration rate and temperature – so that we had a base line against which we could check, to see whether she was improving or deteriorating.

Читать дальше