‘ Stadt Luft macht frei ’, went the old German expression: ‘city air makes one free’. By the thirteenth century small self-governing walled communities were flourishing throughout Europe, separated from the oppressive world of feudalism which dominated life outside. When you entered the gates of the town you passed from the immediate jurisdiction of the prince or king or bishop who controlled the territory into an independent community; you might be a serf or a knight but if you resided in the town for a year and a day you automatically became a free citizen. Townspeople had their own markets and councils, and in the centre one found not a palace but a market square and a town hall. The powerful medieval guilds controlled everything from prices to the quality of goods, from the number of employees in a given business to the accepted working hours, and inspectors regularly combed towns like Berlin ensuring that craftsmen did not advertise their products or undercut fellow producers or deal in foreign goods except during one of the great trade fairs which were held throughout Europe. The proud seals of shoemakers and goldsmiths and tailors also concealed harsh regulations and petty restrictions like the Beeskow Law which dictated that only Germans could be members of a guild, and there were fines for disobeying guild restrictions, fines for wearing incorrect clothing, fines for selling goods on the incorrect day and fines for usury.

The rules were tolerated because they were made and enforced by the townspeople themselves; kings and bishops allowed these freedoms because they benefited from the wealth generated by the towns. 69With prosperity came the creation of their own dynasties and although Berlin had nothing to compare with the great patrician families of Europe like the Fuggers or the Medici some, like the Blankenfeldes, the Rathenows and the Rykes (Reiches), became extremely powerful in their own right. 70Many founded new districts for themselves: the Reiche family created Rosenfelde (now Friedrichsfelde), Steglitz is named after the knight who first lived there, and many streets and surrounding villages still bear the names of their founding families. Increased patrician control was summed up in a document written on 10 April 1288 by Nikolaus von Lietzen, Johann von Blankenfelde and other leaders, in which Berlin cloth cutters were granted the right to create a guild as long as they obeyed the strict laws enforced by the dignitaries of the town – Berlin offered citizens protection and the chance to make money in return for obedience. 71The fortunate citizens of Berlin were indeed ‘free’ when compared to the poor peasants forced to eke out an existence on the land outside its walls.

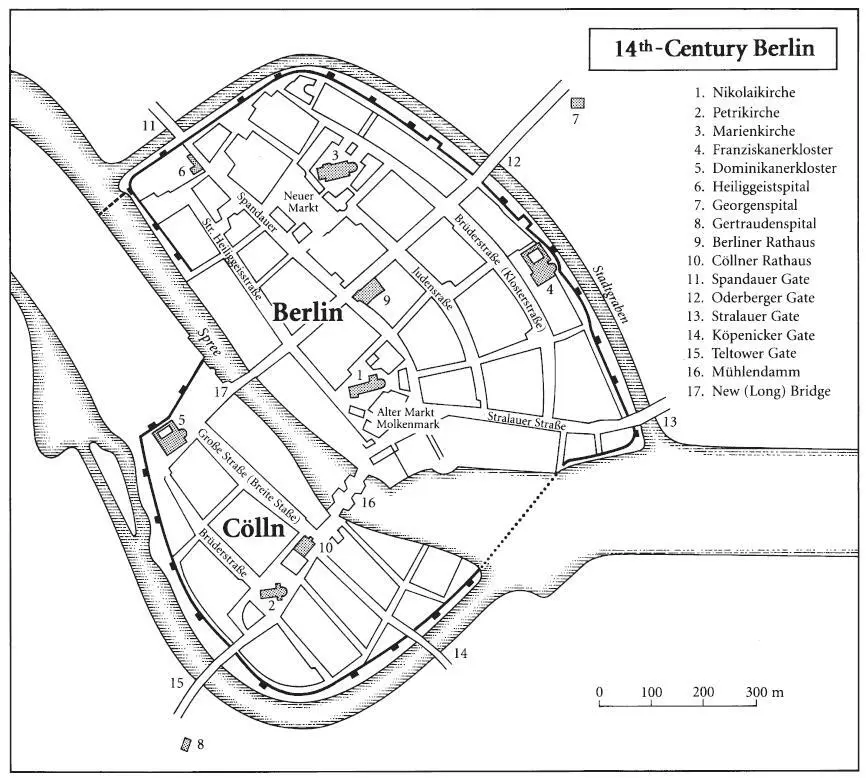

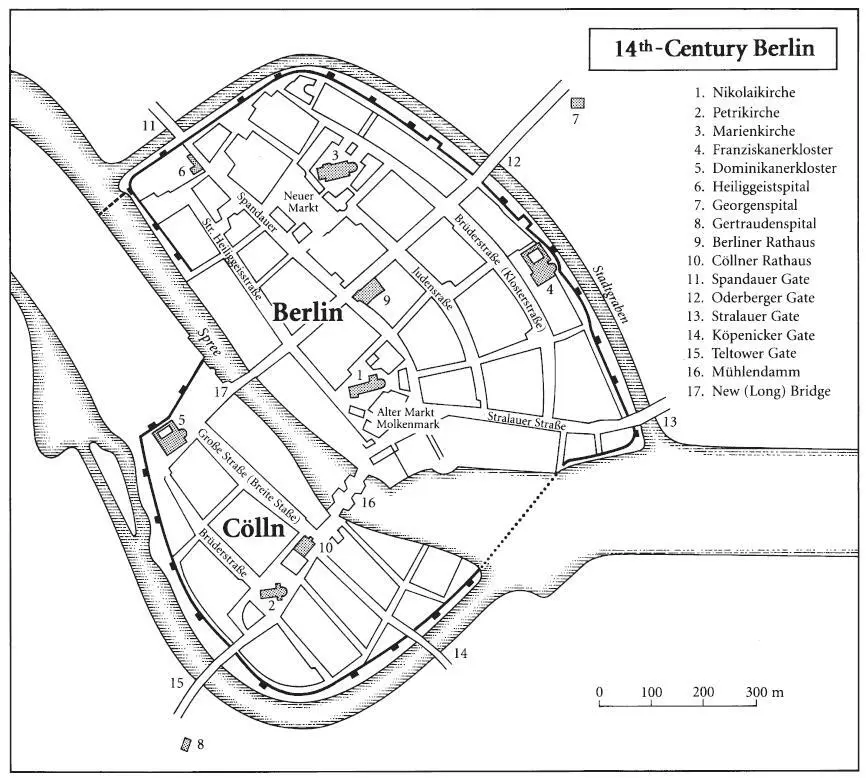

The increase in wealth brought a flurry of building to the town, with the first important permanent structures being churches. The ruins of two early thirteenth-century Romanesque basilicas still lie under the foundations of the St Nikolai and St Petri churches along with more than ninety early Christian graves, but the earliest church to survive was St Nikolai. Started in 1230, with walls of simple round grey fieldstones, it was rebuilt as a late-Gothic hall church. The church of St Petri was founded around 1250; the Marienkirche and the nearby Neuen Markt were started around 1270 and rebuilt after the great fire of 1380. The religious orders were central to the creation of the city: the Franciscan monks were established in the city in 1250, the Dominican monastery was founded in 1297 on the site now occupied by the grandiose Dom, while the Knights Templars set up their cloister south of Cölln, giving their name to Tempelhof. The religious orders brought the first hospitals to Berlin: the Heliggeistspital at the Spandau Gate was built in 1250 and the Georgenspital Leper House was placed outside the Oderberg Gate, now at the edge of present-day Alexanderplatz. The first Berlin wall of fieldstones piled two metres thick was started in 1247 and it was cut through by the Stralau, Oderberg, Spandau, Teltow and Köpenick gates.

In 1256 Berlin and Cölln were linked by a mill dam which could control the flow of water, making it a more convenient river crossing and providing power for a public mill; in 1307 the two towns merged in a formal union and a new Rathaus was built on the Lange Brücke – or long bridge – so that the representatives were actually suspended between the two settlements as they sat in council. The margrave of Brandenburg did not move to Berlin, preferring to stay in the much more luxurious Spandau Castle, but he was represented there by a governor known as the Schultheiss, first appointed in 1247. 72(The name Schultheiss was given to one of Berlin’s famous brands of beer.) The towns were given their own seals; the earliest dates from 14 July 1253 and was produced under the joint authority of the Brandenburg margraves Johann I and Otto III. It depicts the Cölln eagle framed by a great city gate complete with three towers. The Sekretsiegel , the second Berlin seal to depict a bear, dates from 1338 and shows a rather ferocious beast, all claws out, striding across the landscape and dragging behind him a small Cölln eagle attached to his neck by a leash. In 1369 Berlin Margrave Otto granted Berlin the right to mint coins which were to be honoured by the people of ‘Berlin, Cölln, Frankfurt, Spandau, Bernau, Eberswalde’ and others, in effect making Berlin the financial centre of the Mark Brandenburg. 73

Despite such successes Berlin was far from becoming a great city; indeed in comparison to the rest of Europe all the towns of the Mark were backward and primitive. 74The few churches in Berlin were small and unimaginative. There was no great representative architecture of the age and certainly nothing remotely like the magnificent Notre Dame, Westminster Abbey, St Stephen’s in Vienna, the Charles Bridge in Prague, or Magdeburg Cathedral; nor were there beautifully constructed city walls or ornate public buildings. Fourteenth-century Berlin-Cölln covered a modest seventy hectares and contained around 1,000 houses at a time when Paris, Venice, Florence and Genoa contained around 80,000 people and London already had 35,000, making it the largest city in England. 75Berlin could not compete with the great textile cities of Arras and Ghent or with ports like Bruges or Genoa and it lagged far behind in everything from financial acumen to the development of art and culture. Then, on 14 August 1319 the Margrave Woldemar died, bringing the end of the Ascanian dynasty which had governed the Mark Brandenburg from the time of Albert the Bear. Berlin had lost its powerful patrons.

There was no natural heir or successor to the titles held by the family of Albert the Bear, and the vast property passed into the hands of margraves from the houses of Wittelsbach and Luxembourg. Unlike the Ascanians these families had no interest in supporting the strange territory; on the contrary, they were eager to extract wealth to finance their estates elsewhere and increased taxes and fines accordingly. With no protection the Mark was soon targeted by marauding armies and bandits. Polish and Lithuanian troops raided in the 1330s, and in 1349 the Danish king Woldemar – the ‘False Woldemar’ – returned from the Crusades claiming to be Albert the Bear’s long-lost ancestor. When he was denied his ‘inheritance’ he attacked the Mark, burning dozens of villages in the ensuing struggle.

This was not the only disaster to befall the fledgling city. In 1348 the Black Death made its fearsome way through Europe and reached the Mark the following year. Suddenly people began to develop black sores on the palms of their hands or under their armpits, only to die in agony a few days later. One tenth of the population of Berlin succumbed to the bubonic plague and more fell to influenza, smallpox and typhus. Tragically, the Black Death brought the first pogroms to Berlin. The Jews had long played an important part in the region; not only had they traded there throughout the Slavic period but the first Jewish grave dates from 1244 and the Berlin Jewish community was officially founded in 1295, after which Jews and Italians largely controlled the functions of banking and money-lending. This long history did not prevent persecution and after the outbreak of plague Berliners began to blame the Jews for poisoning the wells. There were wild outpourings of hatred, Jews were viciously attacked on the streets and in their homes, and many moved for a time to a protected alley near the present Klosterstrasse which was closed off at night by a huge iron gate. Jews were put on trial and publicly executed for their ‘crimes’. Such violence was by no means unique to Berlin; over 300 Jewish communities were destroyed in western Europe and many fled east, particularly to more tolerant Poland, where they formed the largest community in Europe until the Second World War. 76This first wave of Berlin anti-Semitism ended only on 6 July 1354, when the margrave re-established the right of Jews to reside in the city and founded a Jewish school and a synagogue.

Читать дальше