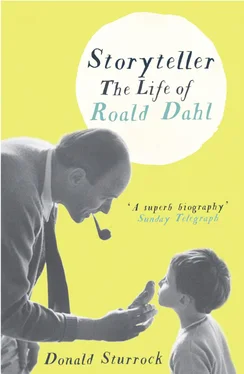

DONALD STURROCK

Storyteller

The Life of Roald Dahl

Copyright Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication PROLOGUE CHAPTER ONE CHAPTER TWO CHAPTER THREE CHAPTER FOUR CHAPTER FIVE CHAPTER SIX CHAPTER SEVEN CHAPTER EIGHT CHAPTER NINE CHAPTER TEN CHAPTER ELEVEN CHAPTER TWELVE CHAPTER THIRTEEN CHAPTER FOURTEEN CHAPTER FIFTEEN CHAPTER SIXTEEN CHAPTER SEVENTEEN CHAPTER EIGHTEEN CHAPTER NINETEEN CHAPTER TWENTY Notes Bibliography Index About the Author Acknowledgements About the Publisher

Harper Press

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2010

This ebook edition first published in 2010

Copyright © Donald Sturrock 2010

Cover photograph © Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Some images were unavailable for the electronic edition.

Donald Sturrock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007254774

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007397068

Version: 2016-10-12

For my parents, Gordon and Margaret

I don’t lie. I merely make the truth a little more interesting …

I don’t break my word—I merely bend it slightly….

ROALD DAHL, from his Ideas Books, No. 1 (c. 1945-48)

Cover

Title Page DONALD STURROCK Storyteller The Life of Roald Dahl

Copyright

Dedication For my parents, Gordon and Margaret

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE Contents Cover Title Page DONALD STURROCK Storyteller The Life of Roald Dahl Copyright Dedication For my parents, Gordon and Margaret PROLOGUE CHAPTER ONE CHAPTER TWO CHAPTER THREE CHAPTER FOUR CHAPTER FIVE CHAPTER SIX CHAPTER SEVEN CHAPTER EIGHT CHAPTER NINE CHAPTER TEN CHAPTER ELEVEN CHAPTER TWELVE CHAPTER THIRTEEN CHAPTER FOURTEEN CHAPTER FIFTEEN CHAPTER SIXTEEN CHAPTER SEVENTEEN CHAPTER EIGHTEEN CHAPTER NINETEEN CHAPTER TWENTY Notes Bibliography Index About the Author Acknowledgements About the Publisher

Lunch with Igor Stravinsky

ROALD DAHL THOUGHT BIOGRAPHIES were boring. He told me so while munching on a lobster claw. I was twenty-four years old and had been invited for the weekend to the author’s home in rural Buckinghamshire. Dinner was in full swing. A mixture of family and friends were devouring a platter brimming with seafood, while a strange object, made up of intertwined metal links, made its slow way around the table. The links appeared inseparable, but Dahl had told us all they could be separated quite easily by someone with sufficient manual dexterity and spatial awareness. So far none of the guests had been able to solve it. As I waited for the puzzle to come round to me, I tried to respond to Roald’s disdain for biography. I mentioned Lytton Strachey, Victoria Glendin-ning, Michael Holroyd. But he wasn’t having any of it. Sitting in a high armchair, at the head of his long pine dining table, he leaned back, took a swig from his large glass of Burgundy, and returned to his theme with renewed relish. Biographers were tedious fact-collectors, he argued, unimaginative people, whose books were usually as enervating as the lives of their subjects. With a glint in his eye, he told me that many of the most exceptional writers he had encountered in his life had been unexceptional as human beings. Norman Mailer, Evelyn Waugh, Thomas Mann and Dr Seuss were, I recall, each dismissed with a wave of his large hand, as tiresome, vain, dreary or insufferable. He knew I loved music and perhaps that was why he also mentioned Stravinsky. “An authentic genius as a composer,” he declared, throwing back his head with a chuckle, “but otherwise quite ordinary.” He had once had lunch with him, he added, so therefore he spoke from experience. I tried to think of subjects whose lives were as vivid as their art: Mozart, Caravaggio, Van Gogh perhaps? His intense blue eyes looked straight at me. That wasn’t the point, he said. Why on earth would anyone choose to read an assemblage of detail, a catalogue of facts, when there was so much good fiction around as an alternative? Invention, he declared, was always more interesting than reality.

As I sat there, observing the humorous but combative glint in his eye, I sensed that, like a boxer, he was sparring with me. He had thrown a punch and been pleased that I jabbed back. Now he had thrown me another. This one was more difficult to parry. It would be hard to take it further without the exchange becoming detailed and perhaps wearisome. I hesitated. I wondered at his own life. He had just written two volumes of memoirs, one of which he had given to me to read in draft. So I knew the rough outline of his first twenty-five years: Norwegian parents, a childhood in Wales, miserable schooldays, youthful adventures in Newfoundland and Tanganyika, flying as a fighter pilot, a serious plane crash, then a career as a wartime diplomat in Washington. I had already told him privately that I found the books compelling. Did he want me to repeat the compliment over dinner as well? It was hard to tell. At that moment the metal links were presented to me and the conversation moved on. Soon, too, his huge pointy fingers had plucked the puzzle from my inept hands and he had begun confidently to demonstrate its solution. Later on, at the end of a meal which had concluded with the offer of KitKats and Mars Bars dispensed from a small red plastic box, he took his two dogs out into the garden. A few minutes later he returned, wished everyone good night, and retired theatrically from the public space of the drawing room into the privacy of his bedroom.

Half an hour later, I was walking up the frosty path from the main building to the guest house in the garden. The atmosphere was absolutely still. A fox shrieked in the distance. I stopped for a moment and looked up at the clear winter sky. I was struck by how many stars I could see. Great Missenden was less than an hour’s drive from London, but the lights of the city seemed far, far away. Some cows stirred in a nearby field. I looked about me. Gentle hills curved around the garden on all sides. At the top of the lane a vast beechwood glowered. The dark outline of the 500-year-old yew tree that had inspired Fantastic Mr Fox loomed over me. In the orchard, moonlight glinted on the gaily painted gypsy caravan that he had recreated in Danny the Champion of the World. An owl fluttered low into the yew. I turned and opened the door to my room.

Читать дальше