The recognition of Scottish independence at Northampton did not finish the matter, and an uneasy relationship between Scotland and England was the norm for the next 300 years – border warfare tempered by the occasional dynastic nuptial. From a Scottish perspective, for many years, union with the auld ally of France looked more likely than union with the auld enemy of England.

And when crown unity did come in 1603 it was through a Scottish king, James VI, becoming King of England. But Scotland remained an independent nation and it would be another century before the Union of the Parliaments.

When that happened, in 1707, Scotland had a collective history of statehood, stretching back for the best part of a millennium: three times the period that has elapsed since.

Scottish dissatisfaction with the government in London has ebbed and flowed since the Treaty of Union. There have been periods when support for the union was in the ascendancy. However, it is also true that every movement for radical change in Scotland, from Jacobite to Jacobin, from crofting Liberals to the early Labour movement, was overlaid with Scottish nationalism.

Even those famous Scots who are often regarded as pillars of the established order have displayed a sneaking sympathy for the nationalist cause. On the Canongate Wall of the Scottish Parliament are inscribed the words that Walter Scott put into the mouth of Mrs Howden in Heart of Midlothian :

‘When we had a king, and a chancellor, and parliament-men o’ our ain, we could aye peeble them wi’ stanes when they werena gude bairns – But naebody’s nails can reach the length o’ Lunnon.’

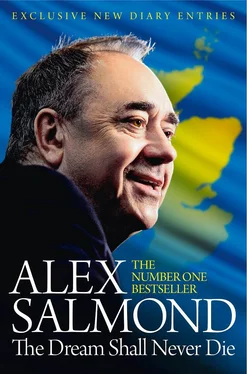

The immediate aftermath of the Second World War was a high point of Britishness, which had a bearing on my own upbringing. My late mother, Mary, patriotic Scot though she was, would probably never have countenanced Scottish independence if her son had not become inveigled into the national movement. She was from a middle-class background and her views had been bolstered by the war: the Churchill pride.

My father, Robert, however, thinks rather differently. When I was a young MP, and didn’t know better, I got into a spot of family bother. I made public the contrast between my mother’s and father’s views, revealing the capital punishment remedy my dad said was appropriate for Churchill’s treatment of the miners.

‘Salmond’s father wanted to hang Churchill’ screamed the newspaper headline. I phoned Dad to apologise.

‘Did I teach you naethin?’ said Faither reprovingly. ‘Hingin was owr guid for thon man!’

The skilled working class like my father – from Robert Burns to the 1820 martyrs, and from Keir Hardie to the early trade union movement – have always been open to the great call of home rule.

James Maxton, the Clydesider MP, speaking in Glasgow in the 1920s in support of a Home Rule Bill (and for a Scottish socialist commonwealth), declared that ‘with Scottish brains and courage … we could do more in five years in a Scottish Parliament than would be produced by twenty-five or thirty years’ heart-breaking working in the British House of Commons.’

So it wasn’t a great leap of faith for my dad to move politically from Labour to SNP in the 1960s. Nor was it for the many others who followed suit in the 1970s, forcing the issue of devolution onto the UK agenda.

The failed referendum of 1979 and the election of Margaret Thatcher seemed at first to have reversed the trend, but in reality it accelerated the underlying shift towards home rule.

A great deal of Scottish identity has been preserved for 300 years through the strength of institutions – Scottish churches, Scots law, Scottish education – and now the myriad of third-sector pressure groups that interact with that institutional identity.

Ironically, Margaret Thatcher’s brand of Conservatism set about dismantling many of the key symbols of Britishness. So British Airways became BA, British Petroleum became BP, and British Rail became lots of things.

But Thatcher inadvertently managed rather more than that. A quarter of a century ago she swept into the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland and, in an infamous address, exposed the crass materialism of her creed. This was too much for the elders and brethren – and far too much for a Churchill Tory like my mother, who never voted Conservative again.

Margaret Thatcher had combined her visit to the General Assembly with an equally ill-fated visit to the Scottish Cup final, where she managed to unite Dundee United and Celtic fans in an ingenious and very effective joint red card protest.

Shortly thereafter, on 16 June 1988, Hansard records a brash young SNP member from Aberdeenshire, fresh from being restored to the House after expulsion for intervening in the Budget in protest against the poll tax, taunting the Prime Minister about what he described as her ‘epistle to the Caledonians’:

Will the Prime Minister demonstrate her extensive knowledge of Scottish affairs by reminding the House of the names of the Moderator of the General Assembly, which she addressed, and the captain of Celtic, to whom she presented the cup?

Margaret Thatcher had given Scottish nationalism a new political dynamic and accelerated the long-term decline of the Conservative Party in Scotland, where it now commands a mere one-third of its popular support of the 1950s.

Other factors were undercutting support for the union. The Scottish economy had been underperforming the UK average for much of the twentieth century. The reasons were deep and complex but one key factor was the export of human capital. Often it was the best people, the people with get up and go, who got up and went.

When I was a lad, thanks to my grandfather’s grounding, I knew that Scots had invented lots of things. He proudly showed me the plaque to David Waldie, born in Linlithgow and pioneer of chloroform, on the wall of the Four Marys pub. He told me that he had worked on the discovery with James Simpson of nearby Bathgate.

I soon discovered that, even beyond Linlithgow and Bathgate, Scotland seemed to have invented just about everything worth inventing – television, telephone, tarmacadam, teleprompter, etc. – and they are just a few examples beginning with the letter ‘t’!

It took me some time further to realise that Scotland’s creative grandeur is not just down to natural ingenuity but springs from our most important invention of all: long before the Treaty of Union, Scotland legislated for compulsory universal elementary education at parish level. Indeed if we look at the list of great Scottish inventors of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries almost all of them were people of humble origins, because almost all people had received an education. Few flowers in Scotland were born to blush unseen.

In no other society on earth, with the possible exception of Prussia, which embarked on this mission two centuries after Scotland, would such ‘lads of pairts’ have had the educational grounding to advance in business, science and medicine.

From the most developed education system in the world sprang the Scottish Enlightenment and out of the Enlightenment came the scientists, innovators and entrepreneurs who established Scotland as the pre-eminent industrial economy of the world by the end of the nineteenth century.

For most of the last hundred years Scotland was still producing the scientists and innovators but, by and large, they weren’t staying in the country. Scotland started to export its human capital to a ruinous degree.

However, towards the end of the twentieth century things started to change.

In the 1980s, when I was working as an economist, I used to do a party trick during lectures by asking the class to write down the six top industrialists or business people in the country. The names provided were invariably a familiar litany of minor aristocrats, most of whom were running their companies less well than their fathers or grandfathers.

Читать дальше