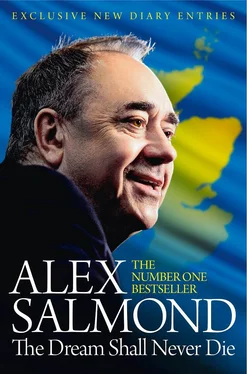

We now have the opportunity to hold Westminster’s feet to the fire on the ‘vow’ that they have made to devolve further meaningful power to Scotland. This places Scotland in a very strong position.

I spoke to the Prime Minister today and, although he reiterated his intention to proceed as he has now outlined, he would not commit to a second reading vote by 27th March on a new Scotland Bill. That was a clear promise laid out by Gordon Brown during the campaign. The Prime Minister says such a vote would be meaningless. I suspect he can’t guarantee the support of his party and, as we have already seen in the last hour, the common front between Labour and Tory, Tory and Labour is starting to break.

But the real point is this. The real guardians of progress are no longer politicians at Westminster, or even at Holyrood, but the energised activism of tens of thousands of people who I predict will refuse to meekly go back into the political shadows.

For me right now, therefore, there is a decision as to who is best placed to lead this process forward.

I believe that this is a new exciting situation that’s redolent with possibility. But in that situation I think that party, parliament and country would benefit from new leadership.

Therefore I have told the national secretary of the Scottish National Party that I shall not accept nomination for leader at the annual conference in Perth on 13th–15th November.

After the membership ballot I will stand down as First Minister to allow the new leader to be elected by due parliamentary process.

Until then I will continue to serve as First Minister. After that I shall continue as member for the Scottish Parliament for Aberdeenshire East.

It has been the privilege of my life to serve as First Minister. But as I said often enough during this referendum campaign, this is a process which is not about me or the SNP or any political party. It’s much, much more important than that.

The position is this. We lost the referendum vote but Scotland can still carry the political initiative. Scotland can still emerge as the real winner.

For me as leader my time is nearly over. But for Scotland the campaign continues and the dream shall never die.

I have believed in Scottish independence all of my adult life.

The roots of this are not, as is often assumed, because of my background as an economist, although that undoubtedly helped. It runs much deeper than that.

In fact it was another Alex Salmond – my grandfather – who first sparked this Alex Salmond’s belief in Scotland. This faith was instilled in me on my grandfather’s knee when I was barely more than a toddler.

My wise granda – Sandy to everyone – had a town plumber’s business in Linlithgow. He was in his late sixties and retired when I was young but kept his hand in by taking on odd plumbing jobs. I was his young apprentice, proudly carrying his tools.

As we trudged round the wynds and closes of the royal and ancient burgh my granda filled me with Lithgae folklore and Scottish history and how the two intertwined. He told me, for example, how King Robert Bruce’s men captured Linlithgow castle by the simple expedient of blocking the portcullis with a hay cart.

More than that, he named the families involved: local folk in the town, families that I knew – the Binnies, the Davidsons, the Grants, the Bamberrys, the Salmonds and the Oliphants. Oliphants were the local bakers. In my child’s eye I imagined the boys in the bakehouse making the bread, dusting off the flour and then charging off to storm the palace.

I was taught no Scottish history at school, but years later at St Andrews University I finally learned the history of my own country and discovered that my granda’s oral tradition wasn’t too wide of the mark – if we forgive his artistic licence in the naming of names. Of course my grandfather wasn’t really teaching me history but about life: how ordinary people could make a difference.

To my grandfather an honest man was the noblest work of God, Scotland was a special place on earth and Linlithgow was a very special place in Scotland. With this grounding it never even occurred to me that there was anything that could not be achieved with sufficient commitment and determination.

Robert Burns once wrote that a similar experience in boyhood gave him a Scottish view of the world which ‘will boil alang there till the floodgates of life shut in eternal rest’.

So it shall be with me.

Everything else I have been taught or experienced, from the science of economics to the art of politics, is overlaid on these foundations: the belief that Scotland is a singular place and that the people of Scotland are capable of great things.

*

It was the best of times. It was the best of times.

For many people the Scottish referendum campaign was the best time of their lives, a far too brief period when suddenly everything seemed possible and the opportunity beckoned for the ‘sma folk’ to make a big impact.

We didn’t win the vote but we did show the establishment circus – and its ringmasters Cameron, Miliband and Clegg – that major change is inevitable. The accepted order has been smashed – and it is the people who have achieved it.

There is a scene in the Ridley Scott film Kingdom of Heaven which sums up where we are now. Orlando Bloom, as the knight Balian, is left defending Jerusalem from the Sultan Saladin with no knights and only the dregs of the army. He has a brainwave: unite the remaining people by making them all knights, much to the disgust of the cowardly Jerusalem patriarch who wants to surrender.

‘Do you think that merely by making people knights they will fight better?’ asks the patriarch.

‘Yes,’ replies Balian.

And he was right. Trusting the common people with the future of their city, or their country, makes for better people and in our case for a better Scotland. Those metropolitan commentators puzzled by the surge in the SNP’s fortunes since the referendum should understand this reality.

Once people have had a taste of power they are unlikely to give it up easily. The process of the referendum has changed the country. Many people felt politically significant for the first time in their lives. It has made them different people, better people.

This book seeks to explain that change, how we got here, why the people became enthused, what caused the big swing to YES, how success was just denied and, most crucially of all, what will happen now.

The events in Scotland underline the ability of grassroots movements to take on political establishments in modern democracies. A new and powerful force has been mustered – modern-day knights if you will. And the international community should sit up and pay attention.

*

But now to our referendum tale. Ours is but a new chapter – albeit a crucial one – in a much older story. Scotland is one of Europe’s oldest nations.

In the late twelfth century, when Balian was busy defending the Holy City, Scotland had already been united as a kingdom for 300 years, with Picts and Scots forced together under the threat of Viking incursions. Richard Coeur de Lion never did manage to win back Jerusalem, but his crusade gave William the Lion of Scotland an excellent opportunity to be released from the feudal impositions Henry II had enforced upon him and therefore Scotland. He was able to fly his Royal Standard (the Lion Rampant) with additional pride.

The next affirmation of Scottish independence was somewhat bloodier but the outcome was the same. Robert de Brus did not seal Scottish independence by the storming of Linlithgow castle in 1313, or on the field of Bannockburn in the following year on midsummer’s day, or even in the Arbroath Declaration of six years later, but at the Treaty of Northampton with England in 1328. However, Bannockburn was still one of history’s decisive battles. It both preserved and shaped the nation.

Читать дальше