A painting by the French artist Louis Philippe Crépin (1772–1851) depicts the action at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The battle demonstrated the extent to which modern naval war could only be fought effectively by wealthy states with developed industries, able to supply and pay for large and well-equipped fleets.

If the cultural differences between battles in different eras and regions make it impossible to generalize about the historical circumstances that explain battle, some explanation is needed for the explosion in the number of battles fought over the last 1,500 years. The eighteenth-century English clergyman Thomas Malthus famously described the problems caused by overpopulation, which result in wars, disease and famine, all of which bring population back to levels the local environment can support. Population growth in the prehistoric age necessitated a search for additional resources, such as pasture, game or raw materials. If this coincides with adverse climate change, as seems to have been the case among the prehistoric native populations of the southwestern United States, then communities are compelled to violent competition for new resources. It would be wrong, however, to see this solely as a prehistoric solution. Changes in population levels in the vast Eurasian steppes partly explain the surges of violent migration and raiding from central Asia for hundreds of years in the first millennium CE. One of the excuses given centuries later for Hitler’s wars of aggression was the German search for Lebensraum (‘Living Space’) so that territory and resources could match population size. When Japan found access to additional resources for her overcrowded islands blocked off by the international economic crisis, the solution was invasion of China and, eventually, the seizure of resources and territory in Southeast Asia.

This suggests crude biological or material imperatives that are all too often overlooked or denied when describing human history, but which clearly act at certain historical moments as a driver towards conflict. There is, of course, an important difference between human and animal populations when faced with food shortages, climate change and competition for resources. Human beings are conscious of what they do. War is clearly the product of growing social and political organization, and the evolution of ideologies or cultures that see conflict as justified by defining the enemy ‘other’, whether it is the Persian Empire, the barbarians of the great migrations or the infidels and pagans defined by the mass religions. In the period from the early medieval world, when battles occur almost ceaselessly, religion runs as a clear thread through hundreds of them. When the Sudanese Mahdist forces attacked the British expeditionary force at Omdurman in 1898, they cried out ‘Fight the infidel for the cause of God!’ as they rushed towards the British machine guns. Not all religions have preached virtuous battle, but those that have – in particular Christianity and Islam in all their different guises – see some form of holy war, whether jihad or crusade, as a divine injunction. The political religions of the last century, fascism and communism, preached simply a secular version of holy war, justified by national struggle or the class war. Ideologies, religious or otherwise, were (and still are) capable of exerting an exceptional psychological pressure to accept self-sacrifice for the sake of a cause defined as noble or sacred.

Finally, there is war as a product of hubris. As more organized states or tribal federations emerged, there arose patterns of leadership that conferred upon kings, emperors and tribal chieftains exceptional power to demand fealty and compel service. The result was the emergence of warrior aristocracies whose members combined tough military service with land ownership or other symbols of distinction. In Europe and Asia, these warrior aristocracies dominated for several thousand years; even when larger and more settled political systems emerged, the aristocracies were expected to provide military leadership, rally their own peasants as military levies, and lead them into battle. This was the Prussian model of aristocracy, but it was not exclusively Prussian and can be found in state and sub-state units for thousands of years. Kings and their warrior elites did not need population pressure or religious idealism to fight, though these might have contributed, but fought over rival dynastic ambitions, claims to land through marriage or contract, the pursuit of wealth and empire for its own sake, or simply because that is what warrior elites did. Battle was the reason for their existence. In Frederick the Great’s Silesian wars in the 1740s, sixty noble generals were killed on the field of battle to ensure that Silesia was seized and held to satisfy Frederick’s lust for territory.

All these explanations played some part in the thousands of battles that have been fought across recorded history, even if each has its own particular historical explanation. Nevertheless, what is striking about any history spanning those 4,000 years are the common characteristics that emerge about the nature of battle itself. John Keegan, in his book The Face of Battle , put together a medieval, early modern and modern battle to illustrate how men ‘control their fears, staunch their wounds, go to their deaths’. But the same approach could cover all the battles in history, if there were as full a record from their participants as there has been for the past millennium. Even though battles are fought in a particular historical context and with changing military technologies, it is still possible to acknowledge their common features, and to understand what the face of battle meant for societies as far apart as the early city-states of the Near East and the developed, industrially armed states of the present. The experience of the volunteers, conscripts, levies, slaves or mercenaries who found themselves in battle on land or at sea is a daunting one. They inhabited briefly a special kind of community, cut off temporarily from the rest of the world, in which nothing mattered at that moment except prevailing over the enemy and avoiding their own death – the ‘truth of battle’.

The hardest thing to understand is the willingness to fight when, as the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes understood more than 300 years ago, the rational thing to do is to run away. On every account we have from the participants, battle is a deeply traumatizing experience with exceptional levels of risk and danger and the ever-present prospect of death, or, what was often worse, a serious wound that would leave you helpless and in agony on the battlefield, later to be battered or speared or bayoneted to death if your side lost, or untreated and likely to die if they won. For most of recorded history, there was no agreed protection for those who were wounded or taken prisoner, and although prisoner-taking could be one of the benefits of battle, particularly if the prisoners could be made to fight for their captors or used as slaves, there are numerous accounts of mass slaughter, mutilation and torture. The power of the victor over the vanquished is absolute, arbitrary and, at the end of an exhausting and dangerous contest, likely to be brutal. Even the emergence of the Red Cross in the 1860s and the Geneva Conventions covering prisoners of war in the twentieth century have not affected the savage fighting in civil wars, nor, in the Second World War, the neglect or killing of millions of prisoners.

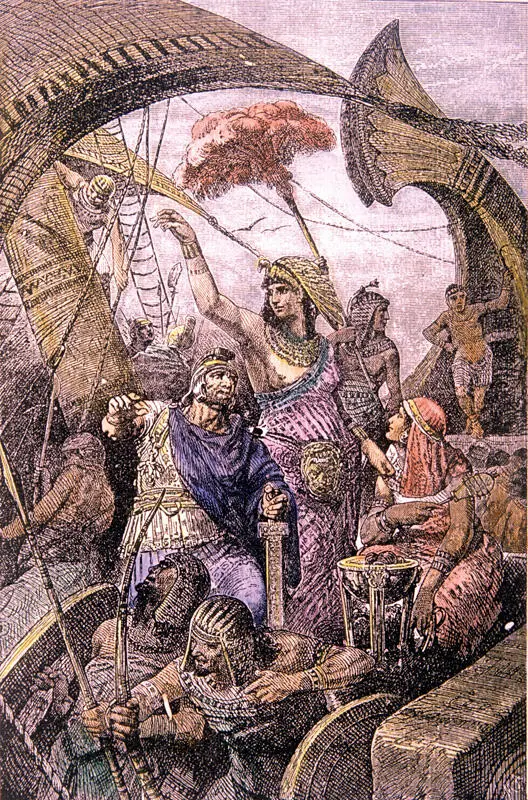

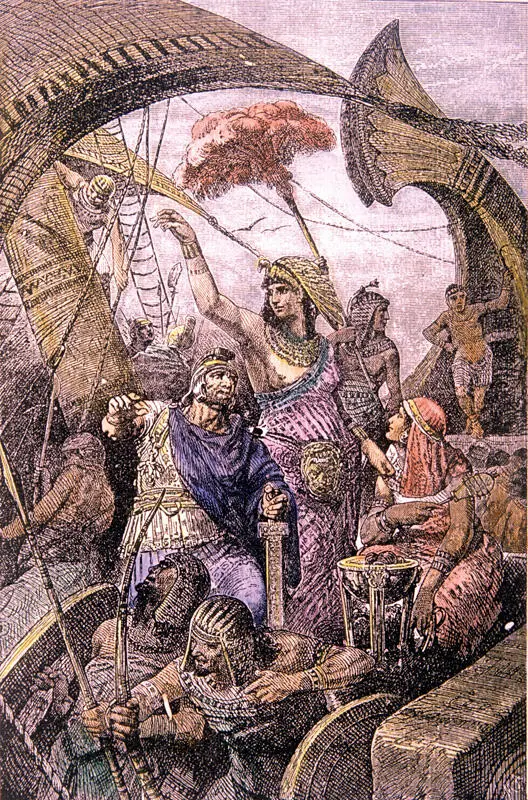

© Ancient Art & Architecture Collection Ltd/Alamy

A nineteenth-century engraving shows the Egyptian queen Cleopatra at the great naval Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. The presence of women in the front line of battle has always been a rarity, and in reality Cleopatra fled from the scene of battle rather than stay and fight.

Читать дальше