John’s response to the awkward situation between us was to write more by himself. Consequently, there were far fewer co-written songs on the last two albums, Dreamtime and 10. These albums were made almost entirely with each member of the group contributing alone with the producer and engineer in the studio. Previously, Jet was the only group member who had been keen to be around the sessions for the whole time. Yet, even he started to be absent whilst 10 was being made.

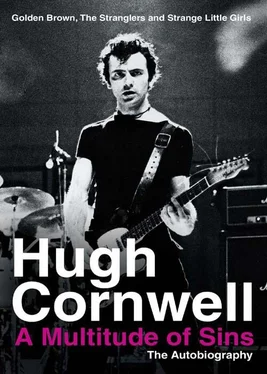

I left the band for a myriad of different reasons. Since then I’ve noticed a change in my attitude to life. I now try to be more philosophical about things. And a weight does seem to have been lifted from my shoulders. There were too many rules and regulations associated with being a Strangler, and who needs any more of those in life? I’ve played with a lot more musicians since I left and my guitar playing has improved. I’m convinced that The Stranglers with me involved was past its sell-by date. I still believe that. Playing is fun again and I’m enjoying playing the old songs. Being in a band can be great fun but it’s also rather like the army. I started to feel that my contribution was not being appreciated by the others, and that it was being resented – and if I ever feel like that, it’s time to move on. Life is too short to waste time with people who don’t value you and there are an awful lot of people out there. I look back on my Stranglers days as an apprenticeship. I learnt a lot about stage skills, songwriting and the music business in general. But bands are not an ideal forum for a personality to express itself, because the collective personality always comes first.

I can think of several moments in my last years in the group that were pivotal in persuading me to take the final decision to leave. The first was following the success of ‘Golden Brown’, which in itself was a surprise to us all, coming as it did after a long period of low-charting single releases. We were on tour in France when Hugh Stanley Clarke from EMI came out to meet with us to discuss what should be the follow-up single. It’s imperative to build on any success in the charts and we all agreed with the record company that a second Top Ten single would bring us right back into the public eye. We met with Stanley Clarke before a gig and he revealed that EMI were keen to release the song ‘Tramp’ as the next single. I was quietly very happy with this, as it was a song I had written alone and presented to the band. I knew that Jet liked ‘Tramp’ but he wasn’t saying much. John immediately rejected the idea, saying that the song was too commercial. Within half an hour, he had convinced everyone in the room except me that ‘La Folie’ was the ideal follow-up single. This was a song we had written together. He had sung it in French, having written the lyrics to a musical piece of mine. It was a reference to the madness of love and was the title track of the current album. It was a beautiful song and could possibly have succeeded if sung in English, but in French it was a non-starter. Its subsequent failure to chart high enough (Number 47) put us back a long way. Later on, we did manage to retrieve the situation somewhat. I got everyone to agree to re-record the song ‘Strange Little Girl’ as the next single. It had been one of our original demos when we were looking for a record deal in 1975 and EMI had turned it down. Tony Visconti produced the whole thing for us and did a great job. ‘Strange Little Girl’ charted at Number 7 on release.

Two further incidents showed me that the others weren’t appreciating my efforts. One happened in Brussels when we were recording the album Feline. Jet and I had stayed very late at the studio one night with our engineer Steve Churchyard to finish a mix of my song ‘Souls’, and we were very pleased with what we’d done. We came to the studio the next day to find the quarter-inch tape of the mix pulled off its reel, stuffed into a large envelope and taped to the studio door with ‘THIS IS SHIT’ written on it. I got as far as packing my bags at the hotel and booking a flight home before I got a call of apology from John on behalf of Dave and himself.

The second incident concerned the making of the video for ‘Always The Sun.’ I had storyboarded the video and everybody approved the idea. We shot the video then the director and I spent a good fifty hours in an editing suite finishing it off. Upon seeing the result, the others said they hated it but didn’t explain why they had approved the idea and the storyboard earlier and also participated in the shoot for it.

I mentioned earlier that John and I had fallen out in Italy. We were backstage after a gig and were swapping our impressions of the performance as we usually did. This particular set had begun with ‘Something Better Change’, an early number which John sang. After the guitar intro, John and I were jumping in the air and landing to coincide with the other instruments starting the song. It was a very dynamic beginning to the set, but we weren’t synchronizing the jump that night, and when I mentioned to John that he hadn’t been on time, he attacked me. He’s had many years of karate training and can quite easily incorporate this into a violent disagreement. He had to be restrained by several people to avoid injuring me. Later on that night, he apologized profusely but I made it clear to him that I was going to have to be very careful what I said to him in future, for fear of my own safety. It was at this point that I resolved to secure some sort of solo recording arrangement, as it was becoming clear that I couldn’t be sure how long our relationship within the band was going to last.

We wrote and recorded demos for the album 10 at John’s house in Cambridge using a small recording set-up in a barn. I would travel up there from the West Country to work for a few days. It made good sense to take a break and catch up with my own personal life and I was intending to leave when John accused me of not being totally committed to the sessions. ‘I’m going to stay here until we’ve finished everything we need to,’ he stated.

It occurred to me that it was very easy for him to continue his private life when he was working in his own backyard but, considering his outburst in Italy, I didn’t want to take any risks by discussing it with him. I did not want to provoke him and just made it clear that I had to take a break, so I left.

So where does that leave us? Rehearsing for a tour to promote 10, and looking forward to touring America, which was the market the record had been produced for. CBS had brought in Roy Thomas Baker, a larger-than-life individual, veteran of numerous Queen albums and teller of many stories about working with rock legends. CBS thought that he could groom our sound for the States, which was a market we had never exploited. Our status there was that of a cult band. We hadn’t been to the US very often, and ‘Golden Brown’ had never had a release there, the general consensus being that it fell between two stools. The Stranglers’ name meant one market, but the song itself meant another, and the marketing gurus over there couldn’t find a way to reconcile the two. The concise streaming of music on American radio left ‘Golden Brown’ out on a limb and unplayable.

Our managers and I had gone over to New York to do some advance promotion for the album. When my part in that was done, I left them there to wheel and deal whilst I returned to London to rehearse with the other three for the UK tour. Our managers then arrived back and immediately came to see us at the rehearsal studios. We were expecting news of US release dates and a touring schedule but instead they told us there were to be no American singles and, more surprisingly, no US tour. They had been unable to interest an American agent to book a tour over there. This was the point at which the thought of leaving the band became a possibility to me. I had been delaying the decision, hoping that touring America might give the group a new energy and maybe some success there. Suddenly there was a huge gap in our work diary.

Читать дальше