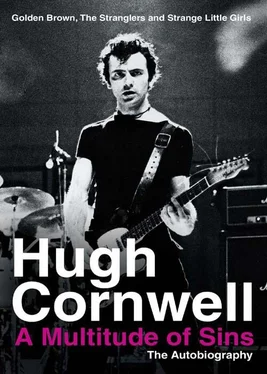

After I left, our accountants clarified that our greatest money-making period had been in those first frenetic years. Our first three albums had cost very little to make, and our tastes were sufficiently crude then that we didn’t expect the luxuries one can get accustomed to. We were so delighted to be successful that we failed to realize we weren’t actually taking home much money. Our managers knew that as long as we had everything we needed, we would be content enough to carry on regardless. On several occasions, a planned tour of Europe would come in costing more than it generated in concert fees, so our managers would go to the record company asking them to pay the difference. This they would do, but charge it against our royalties. The managers would leave with the cheque for the shortfall, and then promptly take their commission off, leaving the tour still in the red, and them in the black. We would go and do the tour, staying in five-star hotels, not realizing that we were paying all the costs. This all helps to paint the picture of a golden goose laying eggs which everybody gets a nice piece of … except the goose. I think it’s pretty accurate. I somehow feel that this part of my story is probably the same as that of a lot of musicians, but I’m not complaining. After all, I got to perform on stage, I got to shag the birds, and I got to take the drugs and drink the booze. And I got my picture in the paper!

The unsung heroine of the punk era is Shirley Bassey. If she hadn’t been selling truckloads of records in the mid-Seventies, United Artists Records wouldn’t have been able to sign The Stranglers, Buzzcocks, Dr Feelgood, 999, Wire and many others. She was the ‘cash cow’ of punk and has never realized it. She also provided us with our first record producer, Martin Rushent, who was the straightest person any of us knew apart from our parents. He’d been producing Shirl’s records for a while and was assigned by the record label essentially to record what we did in live performance. Originally it was thought that we’d release a live album, but as soon as we got into TW Studios in Fulham, with Martin and Alan Winstanley (the house engineer), we were able to improve on our live performance. We’d already recorded demos at TW Studios before being signed to the label, so we had suggested to United Artists that we go there again.

Martin couldn’t believe his luck. He’d been brought in to produce this punk band that he had no experience of, and here was an engineer who had worked with the band before, working in his own studio. Subsequently the recordings went down very quickly and our first album was soon finished, plus four or five extra tracks that we put on our second album. I was fascinated by the whole process of recording. Anything was possible if you had the time. Martin helped us to relax in the studio environment. He had a huge repertoire of jokes, as I did, and would be on the phone to his accountant a lot of the time buying and selling shares. He had his fair share of production ideas too and went on to ground-breaking work with The Human League on their album Dare a few years later.

We’d grown out of Martin’s influence by the time that our third album, Black And White had been delivered, but we did continue to work with Alan Winstanley, who was by then making a fine reputation for himself as a producer in his own right. Alan later teamed up with Clive Langer, from the band Deaf School, and together they produced all of Madness’s hits, and later worked with Morrissey. Their relationship is a similar one to that between Martin Rushent and Alan. Clive Langer is an extremely funny man but is more of a philosopher than Martin ever was. I worked with Clive and Alan on my second solo album, Wolf, whilst I was still in The Stranglers and had great fun working with them. Clive would be discussing his take on life with me at the back of the room while Alan would be working at the desk trying to get some sense out of him. One night Clive spilt a drink over the mixing desk when we were getting drunk in the studio and instead of panicking the three of us collapsed in hysterics.

Such chemistry between people is the secret ingredient in successful working partnerships and that’s why Clive and Alan still work together. There was also that chemistry between John Burnel, the bass player in The Stranglers, and myself for much of the time I was in the band. He would constantly be coming up with great bass riffs for me to write lyrics to and mould into songs, and I had chord progressions that he could put a lyric to. Unfortunately he wasn’t as inspired to work on my musical ideas as I was on his. Add to that the fact that I had more confidence in my voice than he had in his, and you end up with frustration on my part. Gradually, I was turning more and more of my musical ideas into songs by myself, and it was getting easier all the time. John would disappear to France every summer to see his parents and I would be left to finish my songs alone. When we finished our eighth studio album, Aural Sculpture, I had written half of the songs on it. Laurie Latham was with us in Brussels, producing the record on the suggestion of Muff Winwood, our man at CBS Records. Laurie had delivered Paul Young’s first album for CBS which had been a massive seller. Most people aren’t aware that he produced the classic New Boots And Panties!!! by Ian Dury more or less single-handedly, plus most of Ian’s later work. Laurie and I hit it off immediately. He had a great sense of humour, which was quite dry and similar to mine. Laurie’s great forte is his engineering skill in the studio, which means that he can produce without having to explain his ideas to someone else. This saves time and can be crucial to seeing an idea come to fruition quickly. Laurie has since produced two solo albums for me, HiFi and Guilty, doing a brilliant job on both of them. I can honestly say I’ve never laughed so much making a record as I have done with Laurie. He’s a true recording genius.

We were due to work with Laurie again on the next Stranglers’ album, Dreamtime. Laurie had stayed on in Brussels with his family after we’d finished Aural Sculpture, and we were due to repeat the process there with him. But when he heard the songs we had available, he told us he thought we were unprepared and that the sessions should be postponed. He was absolutely right, of course. John and I had had a fallout in Italy (more later) and our writing partnership had suffered. From then on it became a struggle to hold it together. We decamped from Brussels and did some more writing. We never did get back together with Laurie, and it would be nearly twelve years later that I next worked with him.

I’m sure people don’t realize the number of variables involved in making a record. I frequently envy painters the immediacy of their connection to their work. It’s a thought process going from a brain to a hand, then straight on to canvas. It’s simple, precise, and organic. A songwriter writes a song on a guitar. So far, so good. But then it must be recorded. Should it be recorded acoustically with just a guitar and voice, or with something else? What instruments should be used? Who should play these instruments? Where should it be recorded? Who should produce it? Who should engineer it? Should the song be rearranged? Would it sound better in a different key? How many times should the musicians try to record it? Which version is the best one? Once it’s recorded, who is going to mix the levels of the instruments? Which mix sounds the best? Finally, is anybody going to hear it? WHO CARES? It’s such an achievement to make a record that you feel totally drained by the end. And it ceases to be a part of you anymore, the umbilical cord is cut once the recording is finished.

Читать дальше