Making a jelly

Jellies and jams form because of a chemical reaction between a substance called pectin, present in the fruit, and sugar. The pectin (and the fruit’s acids, which also play a part in the reaction) tend to be most concentrated when the fruit is under-ripe. But then of course the flavour is only partly developed. So the optimum time for picking fruit for jelly is when it is just ripe.

The amount of pectin available varies from fruit to fruit. Apples, gooseberries and currants, for instance, are rich in pectin and acid and set very readily. Blackberries and strawberries, on the other hand, have a low pectin content, and usually need to have some added from an outside source before they will form a jelly. Lemon juice or sour crab apples are commonly used for this.

The first stage in making a jelly is to pulp the fruit. Do this by packing the clean fruit into a saucepan or preserving pan and just covering with water. Bring to the boil and simmer until all the fruit is mushy. With the harderskinned fruits (rosehips, haws, etc.) you may need to help the process along by pressing with a spoon, and be prepared to simmer for up to half an hour. This is the stage to supplement the pectin, if your fruit has poor setting properties. Add the juice of one lemon for every 900 g (2 lb) of fruit.

When you have your pulp, separate the juice from the roughage and fibres by straining through muslin. This can be done by lining a large bowl with a good-sized sheet of muslin, folded at least double, and filling the bowl with the fruit pulp. Then lift and tie the corners of the muslin, using the back of a chair or a low clothes line as the support, so that it hangs like a sock above the bowl. Alternatively, use a real stocking, or a purpose-made straining bag.

To obtain the maximum volume of juice, allow the pulp to strain overnight. It is not too serious to squeeze the muslin if you are in a hurry, but it will force some of the solid matter through and affect the clarity of the jelly. When you have all the juice you want, measure its volume, and transfer it to a clean saucepan, adding 500 g (1 lb) of sugar for every 500 ml (1 pint) of juice. Bring to the boil, stirring well, and boil rapidly, skimming off any scum that floats to the surface. A jelly will normally form when the mixture has reached a temperature of 105°C (221°F) on a jam thermometer. If you have no thermometer, or want a confirmatory test, transfer one drop of the mixture with a spoon onto a cold saucer. If setting is imminent, the drop will not run after a few seconds because of a skin – often visible – formed across it.

As soon as the setting temperature has been achieved, pour the mixture into some clear, warm jars (preferably standing on a metal surface to conduct away some of the heat). Cover the surface of the jelly with a wax disc, wax side down. Add a cellophane cover, moistening it on the outside first so that it dries taut. Hold the cover in place with a rubber band, label the jar clearly, and store in a cool place.

Nuts

The majority of plants covered by this book are in the ‘fruit and veg’ category. They make perfectly acceptable accompaniments or conclusions to a meal, but would leave you feeling a little peckish if you relied on nothing else. Nuts are an exception. They are the major source of second-class protein amongst wild plants. Walnuts, for instance, contain 18 per cent protein, 60 per cent fat, and can provide over 600 kilocalories per 100 grams of kernels.

It is therefore possible to substitute nuts for the more conventional protein constituents of a meal, as indeed vegetarians have been doing for centuries. But do not pick them to excess because of this. Wild nuts are crucial to the survival of many wild birds and animals, who have just as much right to them, and considerably more need.

Keep those you do pick very dry, for damp and mould can easily permeate nutshells and rot the kernel. As well as being edible in their natural state, nuts may be eaten pickled or puréed, mixed into salads, or as a main constituent of vegetable dishes.

© Robin Chittenden/FLPA

© Horst Sollinger/Imagebroker/FLPA

Trees

Scots Pine

Juniper

Barberry

Hop

Walnut

Beech

Sweet Chestnut

Oak

Hazel

Lime

Sloe, Blackthorn

Wild Cherry

Bullace, Damsons and Wild Plums

Crab Apple

Rowan, Mountain-ash

Wild Service-tree

Whitebeam

Juneberry

Medlar

Hawthorn, May-tree

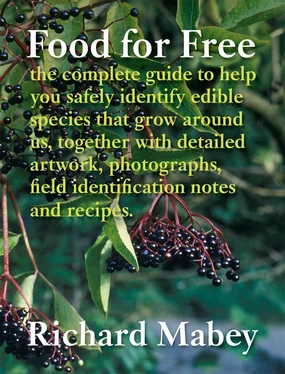

Elder

Oregon-grape

Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris Trees Scots Pine Juniper Barberry Hop Walnut Beech Sweet Chestnut Oak Hazel Lime Sloe, Blackthorn Wild Cherry Bullace, Damsons and Wild Plums Crab Apple Rowan, Mountain-ash Wild Service-tree Whitebeam Juneberry Medlar Hawthorn, May-tree Elder Oregon-grape

A conical evergreen when young and growing vigorously, up to 36 m (118 ft), becoming much more open, and flat-topped with a long bole, when older. Red- or grey-brown bark low down on the trunk, but markedly red or orange higher up in mature trees. Irregular branches, with needles in bunches of two, grey-green or blue-green, up to 7 cm (2½ inches) long. Native to Scotland, and originally much of Britain, as well as much of Europe and Asia.

A winemaker with patience and ingenuity might be able to devise a way of making a kind of retsina by steeping in a white wine base the resin that oozes from the bark of the Scots pine. But it is the needles that are the principal food interest of this tree, because of their strong and refreshing fragrance.

The Scots pine is our only truly indigenous pine, native in parts of Scotland and widely planted and naturalised elsewhere. The needles are quite distinctive, being much shorter than those of other species of pine, grey-green in colour and arranged in rather twisted pairs along the twigs. But the needles of any type of pine will do for cooking, provided they are gathered when fairly young, between April and August.

Anyone who has the patience to extract the tiny nuts from the pine cones will find this nail-breaking work rewarded by a pleasant wayside snack. (The pine nuts used in cookery come from the Mediterranean stone pine, pinus pinea.)

Pine needle tea

Tea made from pine needles is a favourite American wild food beverage, though it has a decidedly medicinal taste. Take about 2 tablespoons of fresh needles, and steep in a cup of hot water for about 5 minutes. Strain and add honey and lemon juice to taste.

Pine needle oil

A recipe for an aromatic oil which makes good use of pine needles’ strong resinous scent simply involves soaking the needles in olive oil for a week or two; the resultant oil is superb for making into French dressings or for cooking meat in.

© Krystyna Szulecka/FLPA, © Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA, © Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA, © Andrew Parkinson/FLPA

© Fred Hazelhoff/FN/Minden/FLPA

Juniper Juniperus communis Trees Scots Pine Juniper Barberry Hop Walnut Beech Sweet Chestnut Oak Hazel Lime Sloe, Blackthorn Wild Cherry Bullace, Damsons and Wild Plums Crab Apple Rowan, Mountain-ash Wild Service-tree Whitebeam Juneberry Medlar Hawthorn, May-tree Elder Oregon-grape

Читать дальше