The few species that are subsequently recommended as roots are all very common and likely to crop up as garden weeds. Where palatable roots of a practical size and texture can be found, however, they are quite versatile, and may be used in the preparation of broths (herb-bennet), vegetable dishes (large-flowered evening-primrose), salads (oxeye daisy), or even drinks (chicory, dandelion).

Green vegetables

The main problem with wild leaf vegetables is their size. Not many wild plants have the big, floppy leaves for which cultivated greens have been bred, and as a result picking enough for a serving can be a long and irksome task. For this reason the optimum picking time for most leaf vegetables is probably their middle-age, when the flowers are out and the plant is easy to recognise, and the leaves have reached maximum size without beginning to wither.

Green vegetables can be roughly divided into three types: salads, cooked greens, and stems. For general recipes see dandelion for salads, sea beet or fat-hen Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

for greens, and alexanders for stems.

All green vegetables can also be made into soup (see sorrel), blended into green sauces, or made into a pottage or ‘mess of greens’ by cooking a number of species together.

Herbs

A herb is generally defined as a leafy plant used not as a food in its own right but as a flavouring for other foods, and most herbs tend to be milder in the wild state than under domestication; being valued principally for their flavouring qualities, it is these which domestication has attempted to intensify, not delicacy, size, succulence or any of the other qualities that are sought after in staple vegetables. You will find, consequently, that with wild herbs you will need to double up the quantities you normally use of the cultivated variety.

The best time to pick a herb, especially for the purposes of drying, is just as it is coming into flower. This is the stage at which the plant’s nutrients and aromatic oils are still mainly concentrated in the leaves, yet it will have a few blossoms to assist with the identification. Gather your herbs in dry weather and preferably early in the morning before they have been exposed to too much sun. Wet herbs will tend to develop mildew during drying, and specimens picked after long exposure to strong sunshine will inevitably have lost some of their natural oils by evaporation.

Cut whole stalks of the herb with a knife or scissors to avoid damaging the parent plant. If you are going to use the herbs fresh, strip the leaves and flowers off the stalks as soon as you get them home. If you are going to dry them, leave the stalks intact as you have picked them. To maintain their colour and flavour they must be dried as quickly as possible but without too intense a heat. They therefore need a combination of gentle warmth and good ventilation. A kitchen or well-ventilated airing cupboard is ideal. The stalks can be hung up in loose bunches, or spread thinly on a sheet of paper and placed on the rack above the stove. Ideally, they should also be covered by muslin, to keep out flies and insects and, in the case of hanging bundles, to catch any leaves that start to crumble and fall as they dry. All herbs can be used to flavour vinegar, olive oil or drinks, as with thyme in aquavit.

Spices

Spices are the aromatic seeds of flowering plants. There are also a few roots (most notably horse-radish) that are generally regarded as spices.

Most plants which have aromatic leaves also have aromatic seeds, and can be usefully employed as flavourings. But a warning: do not expect the flavour of the two parts to be identical. They are often subtly different in ways that make it inadvisable simply to substitute seeds for leaves.

Seeds should always be allowed to dry on the plant. After flowering, annuals start to concentrate their food supplies into the seeds so that they have enough to survive through germination. This also, of course, increases the flavour and size of the seeds. When they are dry and ready to drop off the plant, their food content and flavour should be at a maximum.

Flowers

Gathering wild flowers for no other reason than their diverting flavours would at least be antisocial, and in the case of the rarest species it is illegal under the Wildlife and Countryside Act. Some of the flowers mentioned in this book are rare and should not be picked these days because of declining populations, though many of them have been anciently popular ingredients of salads, and are included for their historical interest.

The only species I advocate picking from are those where removing flowers in small quantities is unlikely to have much visual or biological effect. They are all common and hardy plants. They are all perennials and do not rely on seeding for continued survival. They are mostly bushes or shrubs in which each individual produces an abundant number of blossoms.

Most of the recipes in the book require no more than a handful or two of blossoms, but if you like the sound of any of them it may be best to grow the plants in your garden and pick the flowers there. Many species, such as cowslip and primrose, are commercially available as seed.

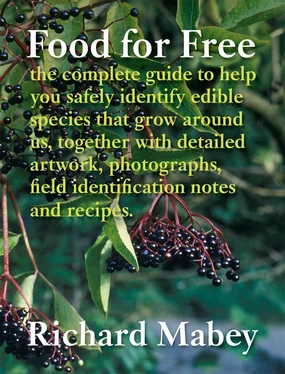

Fruits

A number of the fruits I have included are cultivated and used commercially as well as growing in the wild. Where this is the case I have not given much space to the more common kitchen uses, which can be found in any cookery book. I have concentrated instead on how to find and gather the wild varieties, and on the more unusual traditional recipes.

Almost all fruit, of course, can be used to make jellies and jams. Rather than repeat the relevant directions under each fruit, it is useful to go into some detail here. The notes below apply to all species.

Another process which can be applied to most of the harder-skinned fruits is drying. Choose slightly unripe fruit, wash well, and dry with a cloth. Then strew it out on a metal tray and place in a very low oven (50°C, 120°F). The fruit is dry when it yields no juice when squeezed between the fingers, but is not so far gone that it rattles. This usually takes between 4 and 6 hours.

Most of the fruits in this section can also be used to make wine (not covered in this book); fruit liqueurs (see, for example, sloe gin); flavoured vinegars (see raspberry); pies, fools (see gooseberry); summer or autumn puddings (see raspberry, and blackberry Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

).

Some fruits, notably the medlar and the fruit of the service-tree, need to be ‘bletted’ – in other words, half-rotten – before they are edible.

Читать дальше