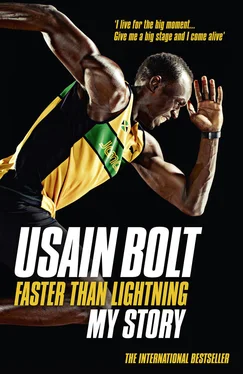

The following day, when I saw Coach McNeil at training I told him the news.

‘Coach, I’ve changed my mind about the World Juniors …’

He smiled, the man looked pleased, and Coach McNeil had some news for me, too. He was waving a clipboard around excitedly.

‘Usain, the guys running those fast times this year aren’t coming,’ he said. ‘They were too old for your under-20s category, so you won’t be racing against them.’

Apparently the serious American 200 metre talent had been replaced by younger athletes with much slower times than my 20.60 seconds personal best. My mood brightened. It felt like a weight had been lifted from my shoulders.

‘Hmm, that’s some pretty nice news,’ I thought. ‘Let’s do this!’

When I think about that conversation now, it was another defining time for me. I’d thought about quitting the World Juniors weeks earlier because I’d been disheartened; my 200 metres times weren’t as mind-blowing as I thought and I figured I was going to lose. But once I’d made the move to compete, once I’d realised there was a shot at winning, my attitude changed. I got excited, and as the weeks passed I became more and more hyped.

At training I ran harder, I quit skipping sessions and avoided Floyd’s place for a little while, but the only doubts in my mind were the fans. I didn’t want to let them down, I didn’t want to be a disappointment to them because the World Junior Championships was so much bigger than Champs. It was an international event and my race was due to be shown on TV around the world. I knew I could shoulder the weight of my school’s expectations, but a whole country? That was some heavy stress right there, and it got to me a little bit.

‘Yo, what’s going to happen to me if I blow it?’ I thought during one sleepless night.

No one could blame me for slightly losing my mind – I was a 15-year-old racing in the under-20s category and I would be battling against athletes three or four years older than me. But when I arrived on the track for my first heats, the competition was everything I expected and much more. Forget Champs – from the first event, the stands at the National Stadium overflowed with people. The noise rattled my eardrums as everyone got behind the home athletes, which only added to the strain I was feeling.

Despite my nerves, I cruised through the qualifying heats and semi-finals. I was feeling good about myself. When the time of the final arrived, it was a warm Kingston evening. The air was hot and dry, but I felt pretty chilled. I thought back to Mom and her chat on our Coxeath verandah. Maybe she’d been right, after all? Maybe there was nothing to worry about.

I got changed into my kit. The fastest Jamaican junior I knew, a girl called Anneisha McLaughlin, was racing in the 200 metres final and I decided to walk out on to the track to catch her and some of the other events. I wanted to soak up the atmosphere.

Well, that was a big mistake. As I walked down the tunnel and into the arena I could see the crowd. They were shouting and screaming, waving Jamaican flags and banging drums. At first I figured Anneisha had started her race, so I quickened my step, but once I got to the edge of the track I realised there was no event taking place. I was the only athlete out there.

‘What the hell is this?’ I thought.

Then I heard a chant rolling around the stadium – it was coming from the one stand and moving around like a tidal wave.

‘Bolt! Bolt! Lightning Bolt!’

The fans were singing my name. It was ringing across the track, the noise was crashing around me. And that’s when it hit me: I was the only Jamaican running in the men’s 200 metres final that night; the people who were going wild out there in the National Stadium, they were going wild for me.

‘Bolt! Bolt! Lightning Bolt!’

Well, I was pretty much messed up after that. As it got to the time of the 200 race, my legs went weak, my heart was pounding out of my chest. I didn’t think I’d be able to walk, let alone run. Straightaway, I sat down in my lane as everything went on around me in super slow motion. The other runners stepped out on to the track, they were warming up and stretching; all of them looked super calm, but I could only stare at the fans waving and screaming in the bleachers. Somebody shouted out that Anneisha had finished second in her final, and that heaped even more pressure on me. I was now the only home boy with a chance of getting gold in the World Juniors. My brain went into meltdown.

‘What the hell is this?’ I thought. ‘People are going mad.’

I was scared. ‘What did I do to myself to put me here? I knew this was a bad idea.’ I had never felt that much pressure in my entire life.

‘I’m a 15-year-old, the kids running here are 18, 19. I don’t need this …’

Still, something told me I had to get to work. For starters, my spikes had to go on, but even undoing the laces felt like a major challenge. I tried to get into the first one, but for some reason it didn’t fit. I pulled and pulled at the heel, desperately trying to work my toes further into the shoe. No give. I jammed my fingers in there and loosened the tongue. Still no give. It was only when I looked down at my feet, after two minutes or so of fiddling, that I realised I’d stuck my left foot into my right spike. That’s how nervous I was.

Stress does funny things to people, and I was falling apart. I tried to get up, to stand, to jog, but I was too weak from the nerves, so I sat down again. Everyone else was doing their strides, going through their final routines, but I was wishing for an escape route – something, anything to get me out of there.

It was so weird. Once I’d been called to the blocks I managed to calm myself for a second or two, but then an announcer called out my name over a loudspeaker and the whole place burst into life again. It felt like the roof of the stadium was about to come off with the noise.

‘Oh God …’ I thought. ‘What is this?’

‘On your marks!’

I settled into the blocks and started to sweat, big-style.

I was officially upset.

‘Get set!’

Don’t mess this up …

Bang!

I froze, I was unable to move and I looked plain stupid. I was stuck to the blocks, as if my spikes and hands had been superglued to the track. It took what felt like a second or two before I reacted to the gun, and by then everybody else had fired off down the lanes. I was dead last because my start had been so slow – but not for long.

When I came out, everything changed. I began to move – and fast. I could see the other runners getting closer and closer as I made the corner, smooth like Don Quarrie, and then I hit top speed. After that, I can’t really explain what happened over the next few seconds because I don’t honestly know. All I can say is that it felt as if somebody, or something, was pushing me down the track. There was a guiding force behind me; it was as if a pair of rocket boosters had been strapped to my spikes. Even with my weird style of running, head back, knees up, I passed everybody until there wasn’t an athlete in sight, only the finishing line. Then it dawned on me: I was the World Junior 200 metres champ.

And it was insane.

Everyone lost their minds. There were people in the crowd screaming, jumping up and down and waving banners. Somebody handed me a Jamaican flag. I wrapped it around my shoulders, because that’s what I’d seen Michael Johnson do when he had won gold medals during the Olympic Games for the USA, and then I did something that would change the way I looked at track and field for ever. I ran towards the bleachers and saluted the fans like a soldier paying respect to his captain. It was my first move to a crowd in any race and the look on everyone’s faces as I did it told me it wouldn’t be the last. The energy that bounced back off the Jamaican people was like nothing I had ever experienced before.

Читать дальше