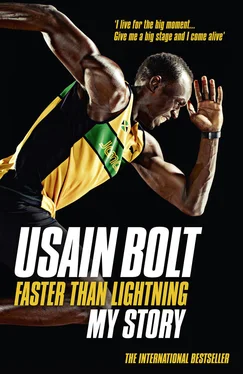

The problem was that I still couldn’t face the hours of training, especially in the 400. Working the 200 metres was so hard, but at least it didn’t kill me. There I only had to run intervals of 300 and 350 metres, time after time, in what was called background training: the tough endurance programme every athlete had to do to prepare them for the season ahead. Background training gave me the strength and fitness to run at high speeds for longer periods of time in a race. It also gave me a high level of base fitness, so if I got injured in a season, I could still maintain my strength and stamina for when I returned to work.

In the 400, though, background training was an altogether different game. I had to run for consecutive reps of 500, 600 and 700 metres. That seemed impossible to me, and often I would vomit on the track after sessions and beg the coach for a rest from all the pain. Even worse, there were exercise routines to be done, because if I was going to be a top runner, my core muscles had to be strong so I could generate some serious power in my legs as I burned around the track. But doing them was tough. One of my roughest coaches was a sergeant-major type called Mr Barnett, and the guy was real awful. He would make us do 700 sit-ups a day. Seven hundred! Even worse was that all the student athletes had to do his abs sessions at the same time. If one person stopped, we all had to start over from scratch.

‘Forget this,’ I thought. ‘I can’t deal with it.’

From then on, I would do anything to duck out of practice, especially if I knew I was working on the longer background runs, or one of Mr Barnett’s torture sessions.

The truth was, I saw running as a hobby rather than the main reason for my spot at William Knibb. At the age of 12, I would skip evening practice sessions at school and head into nearby Falmouth with friends to play video games at the local arcade. The place was owned by a guy called Floyd, and his set-up was pretty simple: there were four Nintendo 64 games consoles and four TVs; it was a Jamaican dollar per minute to play. To get the slot money, I would skip lunch and save the coins Mom had given me for food. Super Mario Cart and Mortal Kombat were my games, I was on them non-stop, and most evenings my hands would hurt from the joystick because I’d played for too long.

Whenever Mom or Dad wanted to know how training had gone, I never told them that I’d skipped a session. Instead I’d shrug my shoulders and act like I’d been running real hard – a yawn or two would usually do the trick. But the fun soon ended when a cousin snitched on me. She had moved into the area near the games room and knew that my dad didn’t like me playing in there. As soon as she spotted me walking into Floyd’s place, she couldn’t wait to tell my parents, and Pops brought out the whoop-ass real bad. I was so pissed at her. I was banned from the arcade, and the school’s head coach, a former Olympic sprinter called Pablo McNeil, tried to explain the importance of my training.

‘You’re running phenomenal times, Bolt,’ he said. ‘If you take this thing serious, can you imagine the times you might establish?’

Mr McNeil was a serious force. He was a stern-looking man with grey hair and a moustache, but back in the day when he was an athlete he had a bunch of wild, afro hair. He looked cool, then. Mr McNeil had been a semi-finalist in the 1964 Games in Tokyo, but despite his experience, the advice didn’t sink in and I carried on fooling around. One evening, after I’d skipped training again, he hired a taxi and drove to Falmouth. He found me at Floyd’s place, hanging out with some of the girls from William Knibb.

My dad’s mood wasn’t improved by the news that my grades were bad too, especially in math. The speed I’d once shown with sums at Waldensia had disappeared, and I couldn’t get my head around the stuff my tutors were trying to teach the class. I became confused at first. I thought, ‘S**t, what happen?’ Then I tried to convince myself that I didn’t need any of the ideas they were trying to put on me.

‘Come on, when am I going to need Pythagoras’s Theorem in real life?’ I thought. ‘Why do I need to know about the hypotenuse formula? Please. ’

It was clear to everyone that I couldn’t care less about school. In my first two years at William Knibb I did what I had to do to scrape through. The teachers tried to convince me that my lessons would help with a sports career, just to give me some extra incentive, but that didn’t help either because I couldn’t imagine that a career in track and field was going to happen – not really. My languages teacher, Miss Jackson, even told me one day: ‘Usain, you should learn Spanish. If you’re going to be an athlete you’re going to travel and you’re going to meet different people and you’re going to want to talk to them. Spanish is a language you should take up.’

I wasn’t impressed.

‘Nah, it’s not for me,’ I thought. ‘I hate Spanish.’ †

Dad’s problems with my slack attitude were the annual, supplementary tuition payments he had to make to the school. He knew that if I failed a year I’d have to repeat it, and that meant an extra bunch of school bills. He got mad again. It was whoop-ass time.

‘If you get held back, Bolt, that’s it!’ he shouted one evening. ‘Anything can happen in track and field – you could be injured and never run as quickly again. If you haven’t got something in your head to fall back on there won’t be anything to help you later on in life.’

To focus me even more, Dad took to getting me up at half past five in the morning. It was crazy. School didn’t start until 8.30, but he wanted me up at the crack of dawn. I would moan every time the alarm went off.

‘What is this?’ he would shout, if ever I stayed in bed. ‘Boy, why are you so lazy?’

Luckily, Mom was a lot softer. As soon as Pops had left for work she would let me go back to sleep. To make sure I wasn’t late for lessons, Mom would then call me a cab to school.

***

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my lazy attitude to training was affecting those all-important competitive performances. Hands down I was the best runner at William Knibb, but when it came to the Regional Championships, I was forever getting my ass kicked by a kid called Keith Spence from Cornwall College. And that pissed me off.

Spence was a mixed-race Jamaican boy and he was pumped up with muscle. The one thing we’d heard about him at school was that his dad had pushed him hard , and I later learned he would make Keith go to the gym all the time. But the extra work had given him an advantage over me because he was more developed, more ripped than I was, even though we were both only 13. His strong abs gave him extra power on the track and I could not take him at the line, no matter how hard I tried. Because I hadn’t bothered with the gym work, because I’d skipped too many of Mr Barnett’s sit-up sessions, I had fallen behind the competition.

But losing to Keith Spence was just as painful to me as those 700 stomach crunches, so after yet another defeat at a regional track meet in 2000, I decided enough was enough. I got furious, and the annoyance gave me focus. Like my race with Ricardo Geddes and Mr Nugent’s promise of the box lunch, I had a goal. I wanted to beat that kid, even if it broke me.

‘Nah, Keith Spence,’ I said to myself on the way home. ‘It’s not going to happen next time.’

It was another big challenge, I had another major adversary, and it was time to step up. I started training a little bit harder, I worked and worked during the school summer break, and as I got more and more into practice, something special happened. I caught my first glimpse of the Olympics when someone showed me some video footage of the 1996 Atlanta Games.

Читать дальше