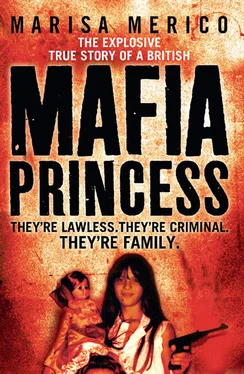

Supposedly, Grandpa Rosario worked as a regular truck driver. It was a pretty transparent ‘cover’ to prove the family had legitimate income. All that was regular were his trips – over the border to Switzerland where cut-price cigarettes were available.

He and Emilio ran the smuggling syndicate. Emilio was only fifteen years old when he began running a team of two dozen teenage drivers to and from Switzerland with secret compartments under the back seats of their Fiat 500s jammed with contraband cartons. In this way, more than ten thousand packs of cigarettes a day were delivered to Nan’s. When they arrived, crow bars were used to wrench forward the back seats to reveal where the cartons were concealed.

The other legitimate suppliers were severely pissed off. They complained to the police. Uniformed officers felt obliged to investigate and they became regular visitors, always leaving with one or two twenty-pack boxes of Marlboros and a kiss on each cheek from Nan. As word got around the precincts the police faces changed and the gifts became more lavish: expensive jewellery, champagne, a stereo system. She could afford the tempting payoffs.

Nan’s ability to obtain cheap cigarettes and move them on without fuss or interference from the police earned her a reputation across Milan. Soon she became a major fence dealing in all manner of stolen merchandise, whether it was a car radio or a gold Rolex, a cashmere sweater or a used video. If anybody nicked anything anywhere it would go to my Nan’s first. She had first refusal. When someone brought a stolen goat she didn’t blink; she tethered it, fattened it and sold it ten days later. There was nothing Nan wouldn’t buy and nothing she couldn’t sell on at a profit.

And she wanted no competition. If any opposition tried to move in, she dealt with it the Calabrian way. She eradicated the problem. She carved out, literally in some cases, a fearsome reputation. With the police in their pocket it was made very obvious the Di Giovines were the kingpins. The family was devious in many things.Nan hadn’t been educated and couldn’t read or write but she could count money. Very well and very quickly. Nan was the Godmother. People would come to her with their problems and she would help. It established loyalty and connections.

She ran her organisation with military precision and controlled it by military methods. The rules and the consequences for breaking or challenging them were severe. If someone had to be punished Emilio would be instructed, given the assignment. If he was pulling the trigger to whack someone on the street at 11 p.m., it was Nan who had told him where to aim the gun five minutes earlier.

And there was always a beef to sort out. If a rival came into the Piazza trying to deal stolen goods or sell smuggled cigarettes, Emilio would go to sort it. The square belonged to the Di Giovines and my nan’s view was that the bastards had to know who was the boss. Emilio was the Enforcer, dealing out beatings, kicking people to the brink of death. He was short, only 5 foot 4 inches tall, because he’d had a milk allergy as a baby. They fed him tomatoes instead, and the doctors said the lack of calcium stunted his growth. But despite his short stature, no one doubted how deadly he was. He had a reputation for being big down there, well proportioned. His family nickname was Canna Lunga, the long cane. His brothers used to joke about it. He was very good-looking, very charismatic. He just had a way.

When he was younger Emilio wore insteps in his shoes to make him taller. But it was confidence that gave him his swagger on the streets; a brash Napoleon, he did not fear anyone. Idiots would always get one warning to clear out the area but the second time they would get hit.

‘Fuck up a third time and I’ll kill you.’ He meant it.

He got results and his fearless determination to protect and control the area for the family attracted businessmen, shopkeepers and families with their own difficulties. They would go to Nan’s, leave cash and wait for Emilio to solve their problems. With that, the family had one of the most profitable protection rackets in Milan. And if protection duties were slow there was also the flip side, extortion.

‘Maria, these guys keep coming in and stealing stuff off my shelves.’

‘La Signora, some fellas smashed up my bar on Sunday night.’

‘Maria, this guy two blocks down is setting his prices so low I am going to go bust and I can’t buy from you any more.’

‘Send for Emilio’ was the chorus, the solution; going to see Nan meant things were dealt with more efficiently and far quicker than if they went to the police – who Nan was paying to keep their noses out anyway. She had all the ends covered in her kingdom. For Nan this was a gold mine.

However, it meant that my kindergarten was an armed compound and my criminal career began when I was a few months old. That’s when I went on my first smuggling mission. The police have the photographs to prove it.

CHAPTER THREE MARLBORO WOMAN

‘I said blow the bloody doors off!’

MICHAEL CAINE AS CHARLIE CROKER,

THE ITALIAN JOB, 1969

When my mum first moved into the Piazza Prealpi apartment it had been customised for crime. Nan was an exceptionable presence in Milan and despite the payoffs police raids were always a threat. There were compartments, nothing more than holes in the wall riddled around behind the kitchen skirting boards, where Nan kept handguns. There were other hiding places – beneath radiators, in cisterns, at the neighbours’ – for more guns and cash. Many of them were places where only a small child’s arm could reach. She was a female Fagin, my nan.

And her den, the apartment, was a constant bustle. Everyone was asking for more – more tobacco, more bottles of booze, more anything-off-the-back-of-a-lorry, and, always, always, more money.

Mum was dazed by the chaotic and crazed lifestyle; there were usually so many people sleeping over she couldn’t count the number. Names? She was still keeping up with the names of Dad’s brothers and sisters. So from dawn till midnight she just nodded hello when the scores of strangers marched into the apartment carrying boxes. Mum had an idea of what was going on around her but never imagined the scale of it; any questions never quite got an answer. She didn’t push my grandparents; she was grateful for all they were doing for her and for me.

In return for the generosity, Mum helped run the household, working with Nan and Dad’s sisters cleaning, washing, ironing and preparing food. There was always someone around to watch me, play with me. I had all the love and attention in the world.

Mum learned to bake bread, make pasta and create authentic Italian meals, mostly using recipes by Ada Boni, the famous 1950s Italian cookery author. She favoured feed-everybody dishes like Chicken Tetrazzini, a casserole with chicken and spaghetti in a creamy cheese sauce. Nan would be up at six in the morning cooking. In between doing her deals, she was at the stove. We’d wake up to the smell of food. It wouldn’t just be sauces; she would cook all sorts of dishes, including veal, chicken, fish, even tripe. She had a freezer full of meat, polythene bags stuffed with cash hidden among the ice cubes, and boxes and boxes of nicked gear in her larders. She was a regular Delia Smith, but with a .38 revolver in the spice cupboard and a couple of other handguns in the dried pasta. Instead of shopping lists, she would have notebook catalogues of dubious contacts for every possible chore, surrounded by cans of chopped tomatoes. Cooking was her therapy. She never went out. She never did anything. She didn’t smoke, she didn’t drink. Her interests were totally family and business, the Calabrian way. And I adored her. She always had time for me no matter what dramas were going on – and being an Italian household everybody knew about them. You heard them! Very loudly. But even the noise was a comfort to me. It meant that the family were all around and I was safe. It was my warm blanket.

Читать дальше