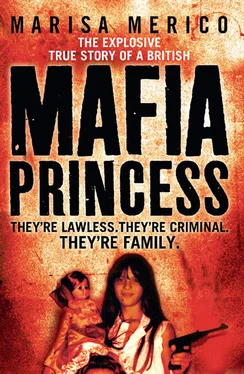

I was seven years old, but that moment is a locked memory card. It was scary for me at the back of the courtroom where I sat with Nan. I kept grabbing her hand. She kept telling me quietly not to worry, not to fuss.

Dad had a beard and long hair and was on a stretcher wearing a white gown covering his bullet-punctured body. It was the first time I had seen him since the shooting.

He looked like Jesus. Appropriately, for the plan was to crucify him.

He was so red-eyed and pale and lost-looking, I wanted to jump over the wooden railings and get to him. I just wanted to hold on to my dad. I never wanted to lose him. It was then, at that moment, when I was seven years old, that a lifetime love, a precious bond, was forged. There was a strange, psychic thing. He hadn’t made eye contact with me up to that point, but then, as my emotions were boiling over, he looked straight at me. While the judge was sentencing him to return to San Vittore prison for a year, Dad smiled and blew me a kiss.

As he was stretchered from the courtroom by two armed guards, he craned his neck and gave me another smile, blew a second kiss and mouthed: ‘ Spiacente [sorry].’

I was no longer just his little princess. I was his Mafia Princess. I would do anything for him.

Nan murmured to me: ‘Don’t worry.’

She could afford to be relaxed. She knew there wasn’t going to be too much hardship. She had made arrangements for Dad to have his favourite foods in jail and any wine he wanted. He’d also have drugs and cigarettes, but not for his own use – he never touched them. The cigarettes were the pennies and pounds of prison, dope of any kind the top currency, to barter and bribe.

Of course, I did worry. Mum was not there with the rest of the family for the court case. She’d already decided she’d had enough of our life in Milan. While Dad was locked up in San Vittore we travelled to Blackpool and stayed with her mum and dad and my auntie Jill. We hung on longer than our usual trips because Mum wanted to see how I would take to life in the UK, but I got physically ill because I was so desperately homesick for Italy, for the family.

When Dad got out of jail in November 1978, it wasn’t a game of Happy Families. I hardly saw him and never knew when I would again. He was totally single-minded about business. And ruthless. Adele’s killing had hardened him even more. He ploughed everything into narcotics smuggling, operating with the Turks to bring in even more heroin. The deals were running into multiple multiples of tens of thousands of pounds. Sometimes a week, always a month.

It didn’t take long for the clock to turn to High Noon. There were other just as determined people as the Di Giovine family. There were gun battles over territory, beatings and killings, and one death led to another and, of course, there was the vendetta. The Yugoslavs were the big threat and Adele’s death still had to be avenged. All I knew of it was that Dad seemed distant most of the time. He didn’t seem to have as much time for me, for anyone.

The family concluded what they called ‘the negotiations’ in a territorial battle that ended with five of the Slav gang dead in a week.

The Di Giovine enterprise, like the drug supply, was endless, and there were always new customers, always the search for more outlets. Patricia Di Giovine, my mum, on the other hand, was searching for an escape. In the August of 1979 we went on holiday to another world, to Calabria, and stayed with my nan’s family. She had relatives, brothers and sisters and their families, throughout the area. My godfather, Uncle Demitri Serraino, was our main host, the patriach. He was lovely, a nice, very particular, elegant man and a bit of a lad. His wife Lidia couldn’t have kids and they’d fed her with hormones that made her really hairy; she looked like a man and had a smell like a man as well. Mum and I had to stay at her house. She was lovely to talk to, but she had bushy hairs under her chin and she used to get Mum to pluck them out.

I sat there worrying: ‘Oh my God, please don’t let me have to pull out the hairs.’ I dreaded the thought of it.

Uncle Demitri and the Calabrian family were set in their old-world ways, their attitudes as ingrown as Lidia’s chin hairs. Nan had bought land, and her brother and his wife, Uncle Giuseppe and Auntie Milina, kept rabbits on some of her acres, which were near their farm. Auntie Milina was unpleasant to everybody and I couldn’t stand her. They told me she could kill people with her bare hands; she was a generale in gonnella, a general in a skirt.

One day I went across to the farm where they kept the pigs and these gorgeous rabbits. Just as she was killing a rabbit for our tea, I pleaded, ‘Please don’t kill that white one!’

But she killed it right in front of me. Just battered his head, and skinned it. It was awful. I’ll never forget it.

I cried and asked: ‘What are you going to do with the skin?’

Auntie Milina held it out to me and said, ‘You can make a pair of knickers if you want.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.