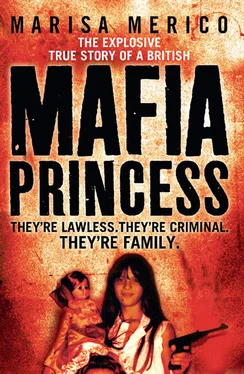

Within minutes he’d returned with her bags all neatly packed. He’d ‘sorted’ the problem. The sex pest would never bother her again. She never found out what he had said – or done. Emilio had no difficulty finding a girlfriend who would let Pat stay until she found another job. By then they had become very much a couple and Pat found out she was pregnant with me.

They’d been lovers for just sixteen days.

Emilio was delighted and his parents were even more so at the prospect of their first grandchild. Emilio was the adored eldest son and Nan opened the doors of her home to him and Pat.

At that time, Nan’s had two bedrooms, a huge front room, kitchen and bathroom, and eleven kids, aged from nineteen downwards, with Auntie Angela only a few weeks more than a twinkle in Grandpa’s eye. Mum and Dad were given their own bedroom. Nan and Grandpa had the other. The rest had to lump it where they could. It was pandemonium. There were kids everywhere, crying, shouting, screaming, laughing, and they all seemed to be fighting. It was like a coven of hysterical little demons.

‘They’re all mad here,’ thought Pat with a grim grin to herself.

It was all falling into place, as if her destiny was mapped out for her. She had no choice. She wasn’t really in love with Emilio. She was still in love with Alessandro and Emilio was her boyfriend on the rebound. He helped her.

When she was a few weeks’ pregnant she went to Blackpool and told her parents, who were distraught. Where was the man who’d got their girl pregnant? Where was this Emilio? They were horrified, in their quiet, behind-the-curtains English way, at how things had turned out. They had hoped Pat would return quickly after her Italian adventure but she had arrived home to announce she was pregnant and was going back for good to raise their first grandchild. Their big, repeated question was: ‘Who is this Emilio?’

Pat didn’t tell them because she still wasn’t sure herself. Instead she offered: ‘He’s a good man. He’s looking after me. I’m happy.’

And deep down Pat really hoped she would be.

When she returned to Piazza Prealpi, she started getting affectionate with his parents, with all the brothers and sisters, learning much if not all about the family’s history. Her emotions were all over the place, but she wanted to belong, to make it work with the young Emilio and the baby that was on the way. She’d never met a man quite like him before.

‘Better,’ he’d always say, ‘to live like a lion for one day than live like a sheep for one hundred years.’

Yet even in the Mafia, there were questions of propriety. Nan put pressure on Emilio to ‘do the right thing’.

Only eighteen days after I was born, on 9 March 1970, they became man and wife at a registry office close to Piazza Prealpi, with Emilio in a dark suit and Pat in an understated brown dress she’d bought at C&A in Blackpool. Grandpa Rosario, who was a witness, looked as if he was at a funeral. Pat’s parents weren’t there. The wedding reception was pasta at Nan’s.

There, Pat overheard her husband and father-in-law talking in the kitchen.

‘Emilio, I’m worried about this girl. She’s going to ask too many questions. She’s English – she won’t understand how things work. She could really fuck things up for us.’

Grandpa was told there was no problem. No one was going to stand in the family’s way, certainly not Pat. It was business as usual.

As if to prove it, Emilio celebrated his wedding night by going out drinking and gambling with his smuggling crews. His bride spent the night alone, looking after the new baby – me – and worrying about our future.

Emilio was nimble-witted, nerveless and remarkably fluent in violence and villainy. He was an heir to that audacity. Just like his mother.

Nan was born on 14 November 1931 in San Sperato, right by the tip of Calabria, on the Strait of Messina across from Mount Etna in Sicily, as deep in the wilds as you can go. Her family were partisans in the mountains during the Second World War, and ‘partisan’ in their world meant they were fighting for each other, for themselves.

They were infamous. They fought fiercely against the Germans, against Mussolini. They were against anybody and everybody. They quite liked the American soldiers for the black market in chocolate. In their own interests, they dealt in protection, extortion and contraband. It was more ruthless than sophisticated.

They were traditionalists, keeping the faiths of the ’Ndrangheta, whose bad business goes back to Italian unification in 1861. The ’Ndrangheta didn’t need secret codes because the Calabrian dialect is impenetrable. In the early days the poor but proud and angry Calabrians banded together against the rich squires who’d taken over what they saw as their land. There were about 400 people in San Sperato and most families managed to grab a chunk of land.

It hadn’t changed much when Nan was growing up with eleven brothers and sisters, a family bred to war in the Calabrian hills. All of them were crushed into a half-built two-bedroom stone house. The Serraino family, like the others, grew olives and lemons, but they also dealt in contraband cigarettes and liquor, mostly cognac stolen from Calabria’s huge Gioia Tauro port – Italy’s ‘passport to the world’ – which was under ’Ndrangheta control. In the shade of melon stalls on the dirt roads all around the countryside, the illicit booze and tobacco were bought and sold. The police collected their payoffs in kind, bottles of brandy and wine, a couple of cartons of smokes, towards the end of Friday afternoons.

‘Have a nice weekend,’ they were told.

It was the family legacy, the family economics, venal but effective: control the trade, supply the demand, and fear no one. Indeed, keep the authorities close to you, pay them off, corrupt or kill them. The Mafia code: keep your friends close, your enemies closer. Perfection would be everybody on the payroll.

It didn’t always work. Some of the police, not many, were straight, or under some sort of regional government control and obliged to make the occasional arrest. That meant that many of those around San Sperato – for everyone had some connection with the ‘black’ economy – spent at least a short time in jail.

That included my great-grandfather Domenico ‘Mico’ Serraino, who was given six months in Calabria Prison for a robbery in the summer of 1947. They didn’t take into consideration any of his other fifty or so offences – that year – as somehow they were never registered in the paperwork.

Domenico Serraino was known as ‘The Fox’, and was cunning in the extreme. His wife, my great-grandma Margherita Medora, was from a similar family. They were peasants who hadn’t had any schooling. He lived in a narrow world: sons of sons were on pedestals, sons of daughters were undeserving of his attention. The sons of sons were gods but grandchildren with a different surname were not allowed to eat with him. If they came close he would chase them away with the back of his hand. Nan was a blessed Serraino.

It was her job to visit her father Mico in prison, to take provisions, cigarettes and wine. The prison guards would receive their ‘allowance’ during the visit. She was very much a sweet sixteen-year-old in appearance but already wily in the way of a born Calabrian, truly The Fox’s daughter. That gave her the confidence to take a chance on romance with the fresh-faced twenty-year-old prison guard who chatted her up during her visits. There was a real sparkle between them. Rosario Di Giovine was new to the prison, new to the area, but linked by bloodline to the South. His dad worked in Rome in the prison service. It was just after the war and work was hard to find so his dad got him this state job. It most certainly wasn’t a vocation.

Читать дальше