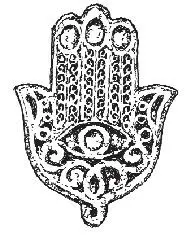

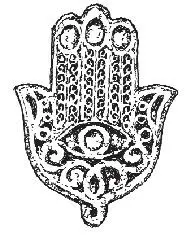

Also known as the Khamsa, the Hand of Fatima is named for Fatima Zahra, the daughter of Mohammed. It is a very ancient symbol, often used as a talisman, and in the Middle East it is ubiquitous, appearing in houses, shops, in taxis, and hotels. The hand is not really shaped like a normal human hand, but has two balanced thumbs and no little finger. The eye in its palm wards off the evil eye, so the Hand of Fatima is a double symbol of protection since the palm, held up, is a forbidding gesture. Khamsa actually means “five” and has relevance for both Muslims and Jews. Peace activists have adopted the Hand of Fatima in recent years; a reminder that the two faiths have many commonly shared beliefs.

If magical charms have more efficacy the harder they are to construct or come by, then the Hand of Glory must be powerful indeed. Noticeably absent from New Age emporia, the Hand of Glory was popular with thieves during the sixteenth century. It was a light, or candle, made from the severed hand of a hanged convict. After this grisly relic was mummified by being embalmed in oils and special herbs, it was turned into a candle using tallow also made from a hanged corpse.

The Hand of Glory was the favored tool of thieves because, once alight, it was said to render household members unconscious. Therefore the thief could go about his nefarious activities undisturbed.

In the south-eastern part of Pennsylvania lives a population of European settlers, primarily from the Rhine area. These people come from different religious communities including Lutheran, Moravian, Quakers, Mennonites, and others. Some of these groups, despite their deeply held religious beliefs, are united by one thing; a thriving belief in witchcraft, also known as Hexerie, from the German, Hexe , meaning “witch.”

Despite their godliness, these are a very superstitious people. One of the popularly held beliefs is that a cross, drawn on the door-latch, will prevent the Devil from entering the house.

The symbols and signs of heraldry act as a sort of historical shorthand, encoding the attributes of the families to whom the heraldic crests belong. The various coats of arms, still in use today, originated in the need to be able to identify opposing armies and single combatants. This necessity dates back to the time of hand-to-hand combat, almost 1000 years ago, although soldiers of much earlier times painted images on their shields that held significance for them, personally, as well as being a sign of identity. Although the blazes, escutcheons, badges, mottos, and crests may at first appear to be a dense forest of impenetrable symbols, their secrets can be interpreted easily. This entry does not pretend to be an exhaustive analysis of the elaborate heraldic codes, but gives a general overview of some of the most commonly used emblems.

THE GREAT SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The Great Seal that is featured on the United States dollar bill contains many heraldic attributes. Here are some features to look out for.

1. Shape—the shield versus the lozenge

Since women didn’t go to war, women’s heraldic designs are depicted on a lozenge-shaped framework (which looks like a diamond tipped onto one point), as opposed to the shield of the male. The lozenge itself, suggestive of the vesica piscis, is a feminine symbol. Although the shield shapes vary, the difference between the two shapes is easily recognizable. Similarly, members of the noncombative clergy use the lozenge or oval shape.

The colors used within heraldry are called tinctures. There are also fields of patterns known as furs, the most common of which is called “ermine,” and resembles the fur of the ermine stoat; the other is called “vair” and comes from a variegated gray-blue colored squirrel. The names of the colors are different, too, retaining their archaic (primarily French) origins.

Gold = Or

Silver = Argent

Red = Gules

Blue = Azure

Purple = Purpure

Green = Vert

Black = Sable

In order that they may remain as clear and visible as possible, a color is rarely laid on top of another color, and the same rule applies to the metallics.

The shield, or lozenge, can be divided in a number of ways. Split in half horizontally it is called “party per fess.” Vertically, it becomes “party per pale.” When it is divided diagonally from left to right, it is “party per bend.” The opposite direction gives “party per sinister.” The “field” of the lozenge or shield can also be split with a saltire cross, or a “normal” one. It can be divided by a chevron, or into three with a Y-shape. There are other variations; lines can also be wavy or curved.

A charge is, effectively, a picture. It can be any object, a symbol, an animal, a plant. Exotic creatures have a large part to play in heraldry; unicorns and dragons join their more realistic counterparts, boars, lions, eagles. The symbolism of these creatures is explored elsewhere in this book, but there may also be a specific link belonging to a family coat of arms, which will have passed into the annals of the family history. The Fleur de Lys has its place as the symbol of the French ruling classes, for example.

This is the element that rests on top of the emblem, effectively crowning it. It tends to appear above the shield, and is the symbolic counterpart of the plume of feathers that knights once wore on their helmets as a sign of distinction and recognition. Because women did not have any occasion to wear a helmet, the lozenge generally has no crest.

This is a phrase that describes the bearer of the heraldic emblem. It acts as a sort of historic mission statement; the name of the family might be used in the motto as a pun or play on words. The motto can be in any language although Latin and French are possibly the most popular.

The shield or lozenge is sometimes supported, generally by animals that stand upright and appear to hold the shield. Again, these creatures bear a relevance to the owner of the heraldic device.

Symbols used within heraldic devices generally are concise shorthand for the qualities of its owner, and the individual meaning can be found in other parts of this book. The lion, for example, signifies valor, the fox, a wily intelligence.

Heraldic devices have meanings of their own; the “mullet,” for example, is not a fish, but a star that denotes the third son. Other curiosities include the Bezant, or gold coin, meaning that the owner can be entrusted with treasure; the escutcheon, a small shield that shows a claim to, or descent from, royalty; a talbot is a hunting hound. A martlet is a symbol of a small bird with no feet, the mark of the fourth son who will have to rely on his own resources since he will not be able to rely on an inheritance. The stirrup signifies action.

There is a whole series of magical protective symbols that the community paint or carve onto the sides of their barns or houses. Called Hex Signs or Barn Signs, these magic symbols are used for a variety of reasons, including averting evil, bringing fertility and prosperity, promoting health, and control of the weather. Many of these signs, which are individually designed, become closely interlinked with a specific family, akin to a coat of arms, and are even tooled into the leather covers of the family Bibles.

Читать дальше