William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Charles Spencer 2017

Charles Spencer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover illustration Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

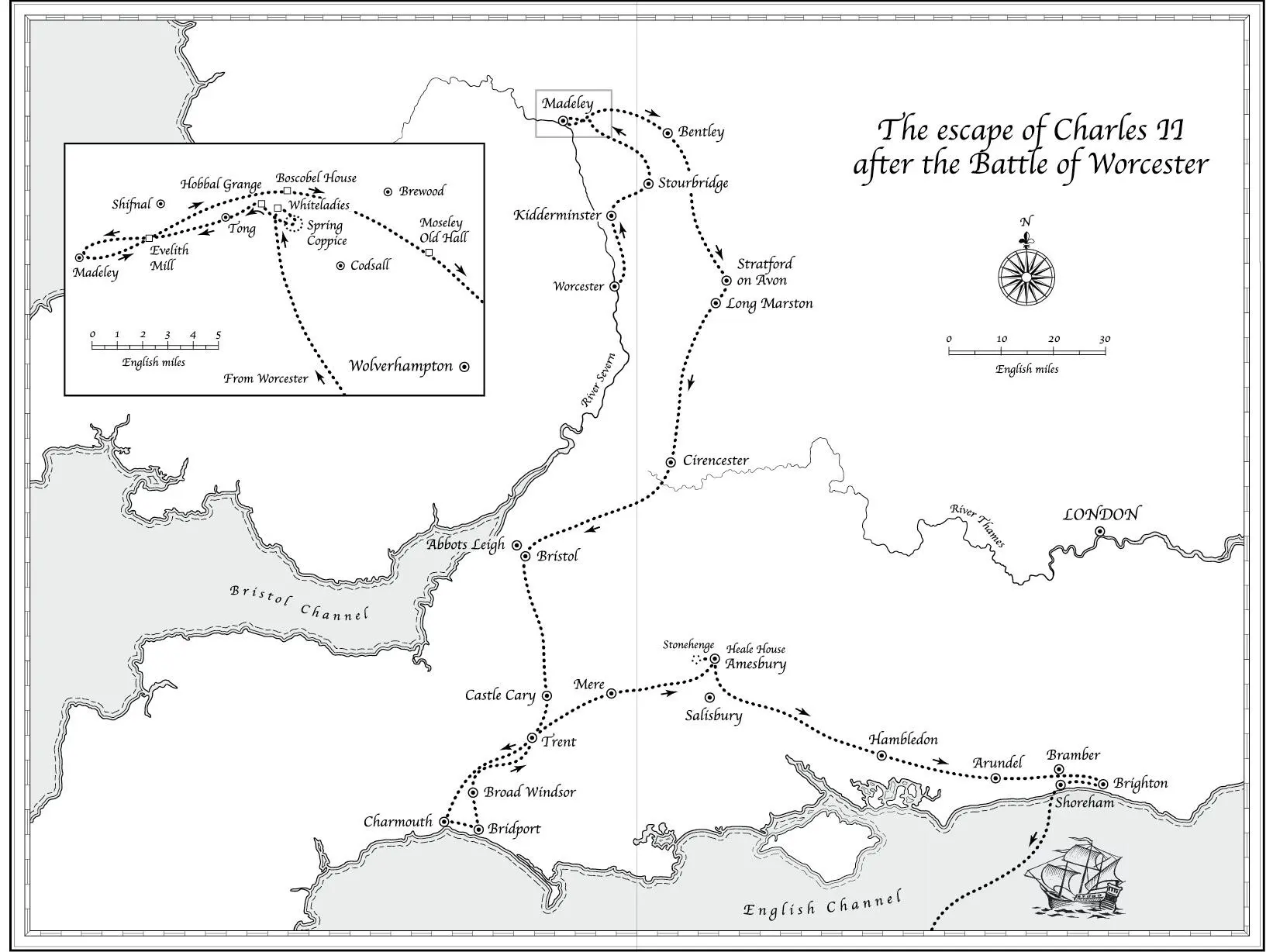

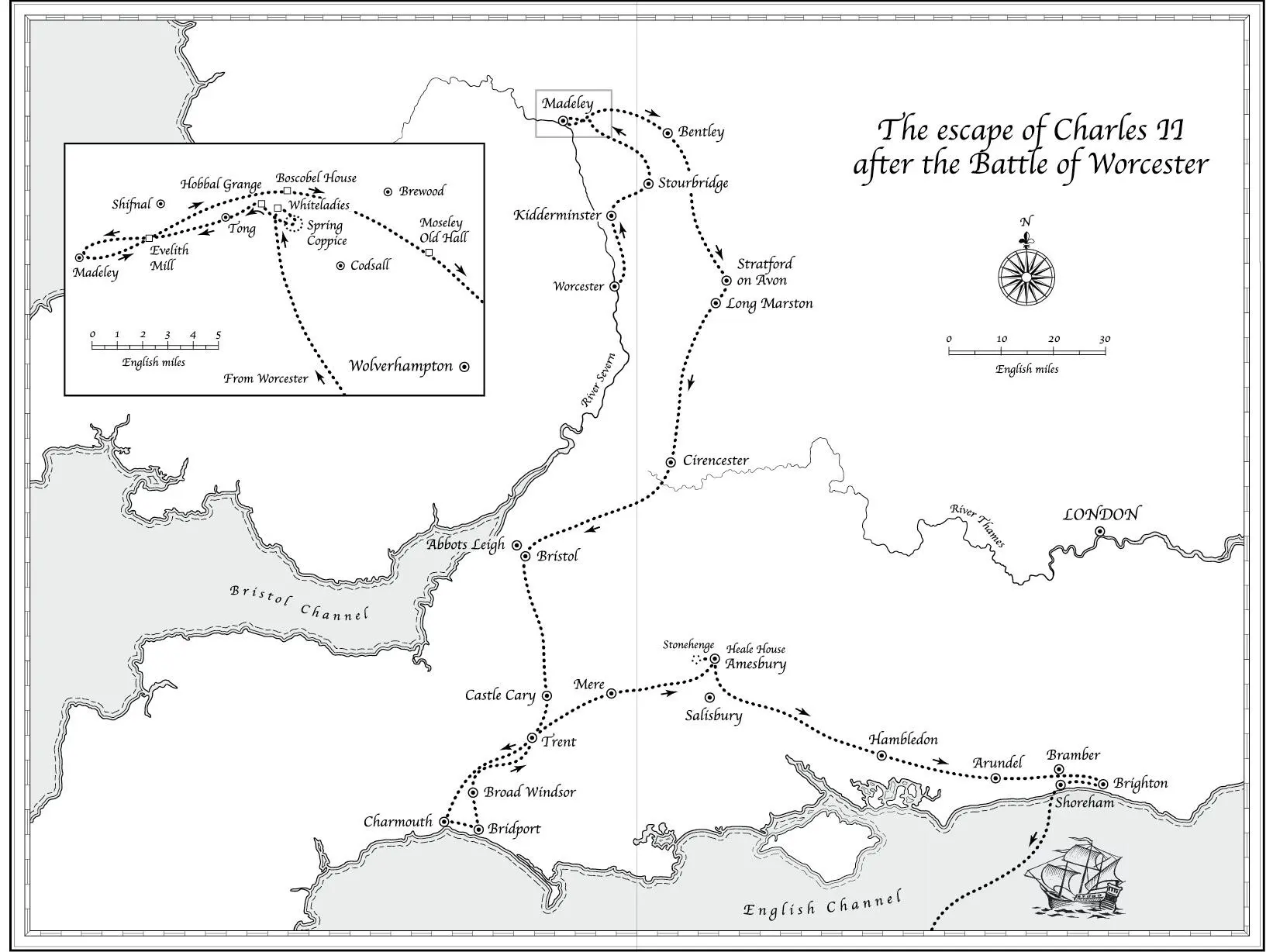

Map by John Gilkes

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008153632

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008153656

Version: 2018-10-01

For Karen

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Introduction

PART ONE: KING OF SCOTLAND

1 Civil Warrior

2 Royal Prey

3 A Question of Conscience

4 The Crown, Without Glory

5 A Foreign Invasion

6 The Battle of Worcester

7 The Hunt Begins

PART TWO: THE ROMAN CATHOLIC UNDERGROUND

8 Whiteladies

9 The London Road

10 Near Misses

11 Reunion

PART THREE: A LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN

12 Heading for the Coast

13 Processing the Prisoners

14 Touching Distance

15 Still Searching for a Ship

16 Surprise Ending

PART FOUR: REACTION, REWARDS AND REDEMPTION

17 Reaction

18 Rewards

19 Redemption

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Also by Charles Spencer

About the Author

About the Publisher

I know how men in exile feed on dreams.

Aeschylus

King Charles II had a favourite story. It was about the six weeks when, aged twenty-one, he had been on the run for his life. Those hunting him down had included the regicides – those responsible for his father’s trial and beheading – who feared him as a deadly avenger; the Parliamentary army, who viewed him as the commander of a defeated, foreign, invasion; and ordinary people, because upon his head sat not the English crown of his birthright, but a colossal financial reward.

This brief period of Charles II’s life stood alone for many reasons. While there were many other times when the bleak reality of his situation fell well short of any reasonable princely expectations, it marked the low point of his fortunes, both as man and royal dignitary. It was uniquely exhilarating for him, in a way that only a genuine life-or-death tussle could be. And it showed off personal qualities that were not always evident in an individual whose self-indulgence and sense of entitlement could infuriate even his most loyal devotees. In his hour of greatest danger, he was proud to note, had arisen within him a quickness of wit, an adaptability, and a hard instinct for survival, that had saved his neck.

In the spring of 1660 Charles returned to England, to claim his throne, on a ship whose figurehead of Oliver Cromwell had hastily been removed, and whose name had been changed from the Naseby (the battle that had been his father’s most punishing defeat) to the Royal Charles . Samuel Pepys was a fellow passenger, and wrote in his diary for 23 May 1660 of how: ‘Upon the quarterdeck he [Charles] fell into discourse of his escape from Worcester, where it made me ready to weep to hear the stories that he told of his difficulties that he had passed through, of his travelling four days and three nights on foot, every step up to his knees in dirt, with nothing but a green coat and a pair of country breeches on, and a pair of country shoes that made him so sore all over his feet, that he could barely stir.’

In the subjects of the kingdom that he had been allowed suddenly and unexpectedly to gain, Charles had found a fresh audience for his pet tale. They would hear repeatedly of their new young king’s exploits. Not that Pepys complained, for the retelling of events that had taken place when he had been a young man of eighteen, six months into his first year at Cambridge University, particularly intrigued him. They awoke, in this most famous of English diarists, the tracking instincts of an investigative journalist. He decided to check how much of the king’s recollections of the six weeks’ adventure were true, and to what extent they had been seasoned by royal fancy, or compromised by forgetfulness.

Two decades later, during one of the royal court’s stays in Suffolk for the horse-racing on Newmarket Heath, Pepys managed to obtain an audience with the king. In his scratchy shorthand (his eyesight had been failing for more than a decade) he took down what Charles remembered of the most electrifying time of his life. Riveted by what he had heard, Pepys quickly secured a second session, his manuscript revealing additions where he included fresh details that Charles had forgotten the first time round.

Meanwhile Pepys resolved to trace those still alive from the motley bunch that had helped the king on his journey from shattering defeat to miraculous delivery. An exceptionally busy man, being at different times a Member of Parliament for two constituencies, and Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, Pepys had hoped to piece together the whole, correct, version of the astonishing tale of escape, and present it as the definitive account. It appears that he had completed almost his entire collection of relevant documents by December 1684, two months before Charles’s sudden death at the age of fifty-four, for that was when he had it bound. A few additions were kept with this volume, including Colonel George Gunter’s report, which arrived at some point during the first seven months of 1685.

There is a paragraph, near the start of Colonel Gunter’s offering, which underlines the way in which those intimately involved in Charles’s escape attempt felt they had been chosen, for whatever reason, to be participants in an event whose eventual outcome had been determined by God. Gunter wrote:

Here, before I proceed in the story, the reader will give me leave to put him in mind, that we write not an ordinary story, where the reader, engaged by no other interest than curiosity, may soon be cloyed with circumstances which signify no more unto him but that the author was at good leisure and was very confident of his reader’s patience. In the relation of miracles, every petty circumstance is material and may afford to the judicious reader matter of good speculation: of such a miracle especially, where the restoration of no less than three kingdoms, and his own particular safety and liberty (if a good and faithful subject) was at the stake. 1

Читать дальше