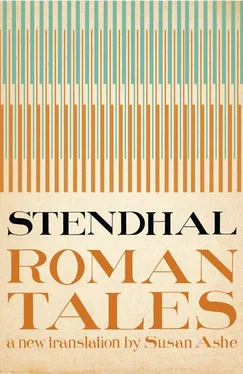

Stendhal

Roman Tales

A new translation

by Susan Ashe

With an Introduction and Notes

by Norman Thomas di Giovanni

To Francis Spencer

Contents

Title Page Stendhal Roman Tales A new translation by Susan Ashe With an Introduction and Notes by Norman Thomas di Giovanni

Dedication To Francis Spencer

Introduction

THE ABBESS OF CASTRO

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

VITTORIA ACCORAMBONI

Chapter I

Chapter II

THE CENCI

Chapter I

Chapter II

Appendixes

1 Background Notes

2 Brigands in Italy by Stendhal

3 Preface to The Cenci by Percy Bysshe Shelley

4 On the Cenci Portrait by Charles Dickens

Footnotes

Glossary

Acknowledgements

Other Titles by Susan Ashe and Norman Thomas di Giovanni in The Library of Lost Books

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

L’Abbesse de Castro , together with the stories ‘Vittoria Accoramboni’ and ‘Les Cenci’, first appeared in book form in Paris at the end of 1839. The volume was among the prolific author’s last completed works; remarkably, he wrote it in tandem with his long masterpiece La Chartreuse de Parme , published that same year. But despite its compelling characters and narrative perfection, L’Abbesse remains one of Stendhal’s least understood and appreciated novels.

We know a good deal about the origins and history of The Abbess of Castro and of Stendhal’s other Roman tales. Sometime in March 1833 he acquired from the archives of certain Roman patricians – it is said from the library of the Caetani family – the right to make copies of a number of old and yellowing manuscripts concerning celebrated trials of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which for the most part ended in the torture and brutal execution of the accused. Among these lurid narratives were accounts of popes dispatching cardinals, executions for murder, beheadings, burnings at the stake, and so forth. Most involved high-ranking Church officials and Roman nobility. In 1834 Stendhal records in the margins of one of his own books, ‘ I have seven volumes replete with Roman exploits, the telling of which in a translation, without any embellishment, would be sufficiently authentic and typical but probably less entertaining that [than] the actual tales .’ (The italics here and that follow are Stendhal’s English, words and phrases of which he habitually interspersed with his French.) On his death the author left another seven volumes of these copied texts. At some point, he singles out the narratives concerning Victoria Accoramboni and the Cenci and sees in some of his material the possibility ‘ To make … a little romanzetto. ’ That is, to draft a short novel.

But by 21 December 1834 the author seems to have shifted his position. On this date, writing to the critic Sainte-Beuve, Stendhal says that when he falls on hard times and needs money he will translate some of these manuscripts, and he asks, ‘What should the collection be called? Roman Tales faithfully translated from accounts written by contemporaries (1400 to 1650). But can the account of a tragedy be called a tale?’

He goes on to tell Sainte-Beuve that these short histories, almost all of them tragic, are written ‘in the common speech of the period’ and can ‘be seen as a useful complement to Italian history’ of their day. He characterizes them as composed in ‘demi-jargon’, by which he meant semi-dialect. But they aren’t – not in the texts I have studied, which are of a simple Italian set down long before the Italian language reached a purified and fixed state.

In fact, Stendhal’s translations are more adaptations than the ‘faithful’ versions he liked to trumpet. As one would expect of an impetuous character like him, he has pared down and uncluttered the Italian texts to make his versions more fluent, more readable. With regard to ‘ The Bishop of Castro and the Abadessa ’, notwithstanding the author’s claims that his sources are two manuscripts, one Florentine, the other Roman – claims that he won’t let us forget throughout the course of the novel – the romanzetto is neither a translation nor an adaptation but an original piece of writing. This is plain to see when the story of Elena and Giulio is compared to other of Stendhal’s Roman tales, the so-called faithful translations. The plot, the character of Giulio himself, the sparkling dialogue, the insights into the protagonists’ psychology, the melodramatic ending are all pure Stendhalian invention. His only source, the thirty-odd-page manuscript account of the affair, the trial, and the scandal of the Abbess of the Convent of the Visitation and the Bishop of Castro, provided no more than a spur, a point of departure, for one of the author’s most perfect creations.

In his lifetime, Stendhal published four of his Roman stories and – as stated – saw but three of them collected in book form. In 1855, some thirteen years after his death, a selection of five of these tales appeared under the name of Chroniques italiennes (a title not Stendhal’s but that of his cousin Romain Colomb and a title that has persisted down the years). From here on, successive editions of these ‘Italian chronicles’ have varied in content according to each editor’s criteria.

Not all the stories in these collections have their sources in the old copied manuscripts. Recent editions have provided us with supplements and appendixes, often with variants, of a number of unfinished texts. These editions have comprehensive introductions and meticulous notes. Stendhal was a tireless scribbler in the margins of his work, particularly in the Italian manuscripts, and these jottings too are brought to our careful attention. The fascination with this material among Stendhal scholars and fans and the continued overlapping presentation of it is almost claustrophobic.

But what was Stendhal getting at in these Italian tales? What did they represent to him? What was he using them to illustrate? One of the constants throughout his career was his love of Italy, and over and over he reiterates a pet theory – such as the following from the introductory pages of the Abbess – that

In sixteenth-century France, a man could show his manhood and true mettle … only on the battlefield or in a duel. And as women love bravery and daring, they became the supreme judges of a man’s worth. Thus gallantry was born. This led to the successive destruction of all passions, including love …

In Italy, a man could distinguish himself as much by the discovery of an old manuscript as by the sword … A sixteenth-century woman would love a man who was versed in ancient Greek as much or more than one renowned for his courage in war. Passions rather than gallantry held sway.

A short note to the reader on the first pages of The Charterhouse of Parma states that ‘the Italians are sincere, honest folk and … say what is in their minds; it is only when the mood seizes them that they show any vanity; which then becomes passion …’ Again, in a preface to his story of the Duchess of Palliano, Stendhal speaks of ‘the unfettered passion that appeared in Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and that died out in our time owing to the aping of French customs and Parisian fashion’. He tells us he will not in his translation ‘make any attempt to adorn the simplicity, the occasionally startling crudeness’ of the narrative. He saw that the essence of this passion rested on the fact that it sought its own satisfaction and was not bound up in vanity. Such passionate feeling required deeds, not words. Stendhal warned his readers that very little conversation would be found in his Italian tales. ‘This is a handicap to my translation, accustomed as we are in our fiction to long conversations by the characters …’

Читать дальше