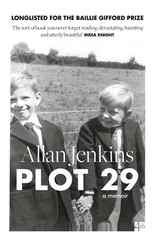

At the party in Ardmore I was introduced to an elderly man, an artist, who had known my parents when they first met. In those days he was a set designer in the theatre. My parents were acting in the premiere of one of my uncle’s plays, Sharon’s Grave, about a tormented man hungry for land and love: ‘I have no legs to be travelling the country with. I must have my own place. I do be crying and cursing myself at night in bed because no woman will talk to me,’ he says. He is physically and emotionally crippled, a metaphor for the Ireland of the 1950s.

Stunted and isolated, Ireland sat on the western edge of Europe, blighted by poverty, still in thrall to the memory of its founding martyrs, a country of marginal farms, depressed cities and frustrated longings, with the great brooding presence of the Catholic Church lecturing and chiding its flock. My parents were children of this country, but they chafed against it remorselessly. The artist told me that he’d sketched them both during the rehearsals for the play.

‘What were they like?’ I asked him.

“The drawings? They were very ordinary,’ he replied.

I said I hadn’t meant the drawings. What had my parents been like?

‘Well, you could tell from early on they were an item,’ he said.

We chatted about his memories of them both. He praised them as actors, and talked about the excitement their romance had caused in Cork. The love affair between the two young actors became the talk of Cork city. The newspapers called it, predictably, a ‘whirlwind romance’. The news was leaked to the papers by the theatre company. Éamonn and Maura married after the briefest courtship. The love affair caught the imagination of literary Ireland. For their wedding the poet Brendan Kennelly gave them a present of a china plate decorated with images of Napoleon on his retreat from Moscow, and there were messages of congratulation from the likes of Brendan Behan and Patrick Kavanagh, both friends of my father. When the happy couple emerged smiling from Ballyphehane church, members of the theatre company lined up to cheer them, along with a guard of honour made up of girls from the school where my mother taught.

Once married they took to the road with the theatre company with Sharon’s Grave playing to enthusiastic houses across the country. In a boarding house somewhere in Ireland, a few hours after the last curtain call, I was conceived.

Several weeks after I met the artist who sketched my parents a brown parcel arrived at my home in London. Inside were two small photographs of his drawings. They looked so beautiful, my parents. My father handsome, a poet’s face; my mother, with flowing brown hair and melancholy eyes. Looking at those pictures I remembered a line I’d read somewhere about Modigliani and Akhmatova meeting in Paris: Both of them as yet untouched by their futures. The artist had caught them at a moment in their lives when they believed anything was possible. There is a poem by Raymond Carver where he remembers his own wedding. This remembrance comes after years of desolation, amid the collapse of his marriage.

And if anybody had come then with tidings of the future they would have been scourged from the gate nobody would have believed.

That was my parents in the year they met, 1960. I was the eldest of their three children, born less than twelve months after they were married and we would live together as a family for another eleven years.

I showed the sketched images of my parents to my eight-year-old son. He looked at them briefly and then wandered off to play some electronic game. I felt the urge to call him back, to demand that he sit down and contemplate the faces of his grandparents. But then, I thought, why would he want to at eight years of age? To him the past has not yet flowered into mystery. Anyway, he knows his grandmother well. Maura is a big figure in his life. He never met his grandfather whose gift for mischief he shares, and whose acting talent has already come down along the magic ladder of the genes.

He is occasionally curious though. ‘What was your dad like?’ he asks. ‘My dad and your granddad,’ I always say. Usually a few general words suffice, before his mind has hopped to something else. But I am sure the question will return when he is older. Just as I ask my mother about her parents, and wish I could have asked my father about his, my son will want to put pieces together, to find out what made me and, in turn, what shaped him.

My parents were temporary exiles from Ireland when I was born. After the successful run of Sharon’s Grave, Éamonn was offered the role of understudy to the male lead in the Royal Court production of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World. They lived in a small flat in Camden Town from where my mother could visit the antenatal clinic at University College Hospital in St Pancras. In those days Ireland had no national health service and an attempt to introduce a mother and child welfare scheme had been defeated by the Catholic hierarchy. They considered it a first step on the road to communism.

In London my mother was given free orange juice and milk and tended to by a doctor from South Africa and nurses from the West Indies. Remembering this she told me: ‘It was the best care in the world. It was the kind of treatment only rich people could afford at home.’

On the day of my birth my father was out drinking and my mother went to hospital alone. It was early January and it had been snowing. A taxi driver saw her resting in the doorway of Marks & Spencer and offered her a free lift to the hospital. By now she would have known a few of the harsher truths about the disease of alcoholism. For one thing an alcoholic husband was not a man to depend on for a regular income or to be home at regular times. Éamonn appeared at the hospital later on and, as my mother remembers it, there were tears of happiness in his eyes when he lifted me from the cot and held me in his arms for the first time.

A week or so later I made my first appearance in a newspaper. It was a photograph of the newly born Patrick Fergal Keane taken as part of a publicity drive for a forthcoming film on the life of Christ. The actress Siobhan McKenna was playing the role of the Virgin Mary in the film and the producers decided that a picture of her with a babe in arms would touch the hearts of London audiences. McKenna was the foremost Irish actress of her generation and was also playing the female lead in The Playboy of the Western World. As a favour my parents had agreed to the photograph. In the picture I am held in the arms of McKenna who gazes at me with a required degree of theatrical adoration.

The declared reason for the embrace had nothing to do with film publicity. The actress had agreed to become my godmother. Strictly speaking this involved a lifelong commitment to ensuring my spiritual wellbeing. I was not to hear from Siobhan McKenna again. Holy Communion, confirmation and marriage passed by without a word.

Thirty years later I met her at a party held in Dublin to celebrate the work of the poet Patrick Kavanagh. My father had come with me. It was a glorious summer’s evening and Siobhan looked radiant and every inch the great lady of the stage. My father approached her and introduced me: “This is Fergal. Your godson.’

Siobhan smiled and threw her arms around me, and the entire gathering of poets and playwrights seemed to stop in their tracks as she declaimed: ‘Sure it was a poor godmother I was to you.’ She stroked my cheek and then stepped back, looking me up and down: ‘But you turned out a decent boy all the same.’

My father laughed. I laughed.

‘That’s actors for you,’ he said.

Éamonn and Maura both loved books. Our home in Dublin was full of them. I remember so vividly the musk of old pages pressed together, books with titles like Tristram Shandy, The Master and Margarita and 1000 Years of Irish Poetry. I have that last one still, rescued from the past. My father liked the rebel ballads:

Читать дальше