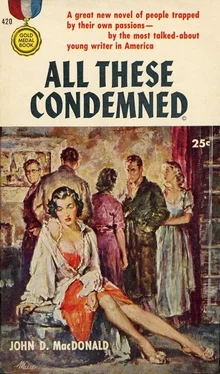

John D. MacDonald

All These Condemned

They reckon death a blessing,

Yet make of life an anxious joy,

A villa thin with gilded laughter,

All these condemned.

DECIMUS JUNIUS JUVENALIS

Satire Number Twelve

Chapter One

(Noel Hess — Afterward)

When at last they found her and took her out of the water I knew I had to go down and look at her. It was more than that sweaty curiosity that surrounds the sudden death of a stranger on a city sidewalk. But there was some of that, too. In all honesty I had to admit that there was some of that, too.

I had left Randy, my husband, asleep in the bedroom she had assigned to us, that smallest of the guest bedrooms. I supposed she had selected it coldly for us, with an objective consideration of our status, half guest, half employee.

Randy had remained awake for a time, dithering about the future, growing increasingly more haunted, until at last emotional exhaustion had taken him, aided a bit by the sleeping pills I began to use long ago, when he first took her on as a client, even before her affairs became his exclusive concern, before she began to devour him with the dainty and absentminded finesse of a mantis.

I had left him there and gone to the big living room, overlooking the lake. There was one small light in the room, in a far corner. A mammoth trooper stood at parade rest, hands locked behind him, leather creaking as he breathed with big slow lungs, looking out the window at the pattern of the lights and the boats. I wondered where the others were. I felt very tiny and feminine beside the trooper. He smelled of wool and leather and, oddly, the woods.

“It must be getting chilly out there,” I said. “I could have Rosalita make some coffee.”

He looked down on me. “That’s been taken care of, ma’am.”

His tone made me feel ineffectual. “Do you think there’s much chance of finding... the body?” I asked him.

“Lake bottom is bad on this side, ma’am. Lots of big rocks. They keep hanging up the grapples on the rocks. But they’ll get her. They always do.”

“There seem to be an awful lot of boats out there.”

“People around here pitch in when there’s a drowning. I don’t know as I remember your name. I’m Trooper Maleski.”

“I’m Mrs. Randolph Hess.”

“I got you placed now, Mrs. Hess. Your husband is another one worked for her. Hard to keep people straight here. Some of them in pretty bad shape when we got here. I guess there was a lot of drinking.”

“Not everyone,” I said, and I wondered why I should be so defensive.

“She put on a lot of parties here, they tell me. Pretty fancy layout. Lot of privacy. You get a lot of drunk people around the water and sooner or later you’re going to have an accident.” His voice was full of ponderous morality. We had kept our voices low. It seemed instinctive in the wake of death.

“I guess this Mrs. Ferris was a pretty well-to-do woman.”

“A wealthy woman, Mr. Maleski.”

“They’ll be reporters here in the morning, I’d say. They’ll get the word and drive up here. Or maybe rent a float plane, the smart ones. What kind of job has that fellow Winsan got?”

“He’s a public-relations man.”

“I get it now. He’s out in one of the boats trying to help out. He’s sure eager to find her before any newspaper people get up here. I guess he doesn’t want them to find out she was swimming naked. But I’d think that would come out in the coroner’s report anyway.”

“Steve would try to prevent any scandal he could, Mr. Maleski.”

“He’s got himself a job this time. They’d already started dragging for her when that deputy sheriff found her swimming suit shoved in the big pocket of that robe. It makes it harder, dragging for her.”

His slow words made a mental image that was, for a moment, entirely too vivid. The room went far away from me and there was a noise like the sound of surf in my ears. Reality returned slowly. I stood beside him and we looked out. The gasoline lanterns on the boats made vivid patterns on the water. The lights were so perfectly white they looked blue. In contrast the flashlights and the kerosene lanterns were orange.

The look of lights moving on the water stirred some reluctant memory in me. It took a long time to bring it clear, as though I forced a key to turn in a rusted lock. Then I remembered and was saddened by the memory. When I was small my parents had taken me to the west coast of Florida, to a shabby little fishing village. There had been a secret in the house. I was aware of the existence of a secret, without knowing what it was. I knew only that it was bad. People were always talking in whispers in the next room. And one night my father fell down and died, and I knew what the secret had been. We had rented a house on a bay there, and during the October nights the commercial fishermen had spread their gill nets in the bay waters, and they had lights on their staunch and clumsy boats, and there had been a great number of them out the night my father had died. It had perhaps been a very good night for fishing.

The trooper had been silent a long time. He said, quite unexpectedly, “You know, Mrs. Hess, I can’t get over that Judy Jonah. I guess I’ve seen her on the TV a hundred times. I used to think she was the funniest woman in the world. She hasn’t seemed so funny lately. But anyway, I always thought she was a great big woman. She’s not much bigger than you are, is she?”

“They say you look bigger than you are.”

“That must be it. I guess she hasn’t got much to be funny about tonight, eh?”

“Not very much.”

“You could have knocked me over with a pin feather when I walk in and see her. Last person in the world I expected to see up here in the woods.”

“Do you know where she is now, Mr. Maleski?”

“She was down on the dock a while back, just looking, wearing a man’s jacket. She must have gone around in the back someplace.”

I thought of Judy. She wasn’t going to do any more weeping than I would. Not over Wilma Ferris. We had other things to weep over.

“Have you been up here before? I guess you would have,” the trooper said.

“Many times.”

“I guess she put a lot of money in this place. Fanciest place for miles around. Maybe in the whole country. You know, I always thought it was a kind of crazy house, all this glass and a flat roof in snow country, and those terrace things sticking out. I mean it looks funny as hell from the lake when you’re out in a boat. But standing in here like this, I guess a fella could get to like this sort of thing.”

“That was her stock in trade.”

“What do you mean, Mrs. Hess?”

“The way people could get to like this sort of thing.” The way Randy got to like it too well, and what it was doing to Mavis Dockerty while Paul had to stand by and watch it happen to her, and the way Gilman Hayes was soaking it all up. Even Steve Winsan and Wallace Dorn and myself — all of us jumping and whirling in marionette blindness while Wilma Ferris toyed with apparent purposelessness with our strings.

“I guess I see what you mean,” the trooper said. “She used it for sort of business purposes. Like getting a fella off guard.”

“Like that,” I said.

“There was the eight guests and Mrs. Ferris and the three Mexican servants. Twelve in all. Is that right?”

I counted them in my mind. “That’s right.”

“If anybody wants servants up here, they got to bring them up. There isn’t anybody up here does much of that kind of work. How about these Mexicans? Where’d she find them?”

“They came up from Mexico. She has a house down there. In Cuernavaca. She has them come up here for the summer.”

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)