Джон Макдональд - Half-Past Eternity

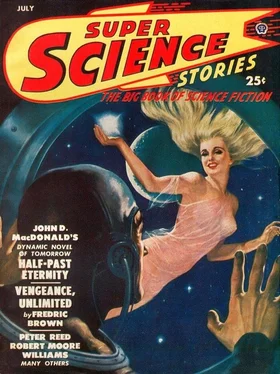

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джон Макдональд - Half-Past Eternity» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Kokomo, Год выпуска: 1950, Издательство: Fictioneers, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Half-Past Eternity

- Автор:

- Издательство:Fictioneers

- Жанр:

- Год:1950

- Город:Kokomo

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Half-Past Eternity: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Half-Past Eternity»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Half-Past Eternity — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Half-Past Eternity», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

John D. Macdonald

Half-Past Eternity

Chapter One

Stolen Lives

The kid didn’t talk. Nat February talked. Which is what you might have expected.

The kid had a punch like the business end of a mule, sure, and he kept boring in, shuffling flat-footed, game all the way through. But everybody on the Beach knew that the kid, who, by the way, at thirty-one was a kid no longer, had suffered slow degeneration of the reflexes to the point where his Sunday punch floated in like a big balloon and he could be tagged at will.

The way the bout happened to be set up was on account of Jake Freedon, a fast, vicious young heavy, not being able to get his title bout. The champion was justly leery of young Jake and the only thing for Jake’s managers to do was to line up every pug in the country and let Jake knock them over. Sooner or later the pressure would grow heavy enough for the title match to be a necessity.

The Garden crowd was slim. There was no question about Jake Freedon winning. The kid was all through in the fight game although nobody had told him that yet. The odds hovered around twelve to one.

This old man had come to Nat February, having been guided to him after three or four days of asking questions. Nat was hard at work on a cheese blintz and resented the intrusion. He had his usual little group with him and Nat was about to give the brush to the old gentleman when same old gentleman said with tremulous dignity that he wished to speak alone to Nat February. So saying, he pulled a wad of currency out of his wallet that looked entirely capable of choking the fabulous cow.

Nat gave the sign and his cohorts cleared out.

“I,” said the old man, “wish to bet on Mr. Goth in the contest tomorrow night.”

“Mr. Who?”

“Goth. He is scheduled to box a gentleman named Freedon.”

“Oh! The kid! Let me get this. You want to bet on the kid. A poor old guy like you with holes in his socks wants to bet the wrong way. You’re going to make me feel like the guy with his mitt in the poor box, uncle.”

“Your emotional reaction is of little interest to me, Mr. February. I understood that if I stated my wager clearly, you would take my money and give me a slip of paper testifying as to my wager. I understand that in your — ah — profession, you are considered to be one of the most thoroughly ethical and — ah — well financed.”

“What have you got there, uncle?” February asked.

“Thirty-two hundred and fourteen dollars. I had hoped to bet thirty-two hundred and twenty-five, but my expenses were higher than I had planned and it has taken longer to locate you.”

“The whole wad on the kid, eh?” February was not at all troubled by removing the funds from the old gentleman. It appeared to him that if he did not do so, someone else would.

“Yes, young man. All of this I would like to bet on the circumstance of Mr. Goth striking Mr. Freedon unconscious during the first three minutes of their engagement.”

“Holy mice, uncle! The kid to knock Jake out in the first round?”

“Exactly. They told me you would quote the odds on that particular thing happening.”

“I don’t want to take your money.”

“I insist, Mr. February.”

“Okay. Thirty to one.”

“You will please write out the paper for me, Mr. February, and tell me where I can find you directly after the fight. I shall expect you to have ninety-six thousand four hundred and twenty dollars with you. I am not — ah — superstitious about thousand-dollar bills.”

“You’ll bring a satchel, eh? Maybe a carpet bag?”

“If you consider it necessary.”

For a fraction of a second Nat February’s calm was shaken. But he quickly reviewed the past record of both the kid and Jake Freedon. It seemed highly probable that if the two of them were locked in a phone booth, it would take the kid more than three minutes to lay a glove on Freedon, much less chill him.

“What’s your name, uncle?”

“Garfield Tomlinson.

Nat wrote out the slip, counted the money, pocketed it, pushed the slip across (he table. Tomlinson picked it up, examined it, sighed, put it in his wallet, now almost completely empty.

“And where will I find you?”

“Right here, uncle. In this same booth. They save it for me. I don’t wish you any had luck, but I hope you won’t be looking for me.”

Nat February had bad dreams that night. In the morning, trusting more to dreams than to judgment, he shopped around town until he found odds of fifty to one. He placed a thousand of Tomlinson’s money there, accepting the jeers of the wise ones. In doing so he cut his maximum profit to twenty-two hundred and fourteen dollars, but his maximum loss went down to forty-six thousand four hundred and twenty He still felt uneasy. He looked up Lew Karon in the afternoon, talked Lew into offering sixty to one and placed a bet of eight hundred twenty-five. Now, if the old man’s bet was bad, he still had a profit of thirteen hundred and eighty-nine. But if the old man had a reliable crystal ball — and he had acted like a man who at least had access to one — Nat would profit to the extent of three thousand and eighty dollars. If the old boy got wise and misted on getting his original bet back, which he had every right to do, as well as the ninety-six thousand four hundred and twenty, then Nat would be out one hundred and thirty-four bucks. He felt comfortably covered.

He sat in his usual fifth-row ringside and dozed through the preliminary bouts, making a little here, losing a little there — but always more making than losing.

When the main came on and the kid fumbled his way over the ropes, his gray battered face wearing its usual dopy look, Nat cursed himself for cutting his profit with the overlay. Jake Freedon bounced in, smiling, confident, young, alert.

After the usual formalities the house lights dimmed and they came out for the first round. The kid shuffled out, slower and dopier than ever. They touched gloves. Freedon flicked the kid with a searching, stinging left jab and danced back. The kid stood, flat-footed. The referee motioned to him to fight.

Nat’s eyes bulged and his hands clamped on the arm of the chair. He shut his eyes and shook his head.

When he opened his eyes again he saw what he thought he had seen in the first place. Freedon, spread-eagled on his face, his mouth in a puddle of blood, the referee jumping out of his stunned shock to pick up the timekeeper’s count. The referee counted to eight, then spread his arms wide and Freedon’s seconds jumped in to cart him back to the stool.

Nat shook the man beside him. “What’d you see happen?”

“Gosh!” the man said. “Gosh!”

“What happened?”

“Well, the way I see it the kid kinda jumped at Freedon, real fast. Fast as a flyweight. It looked to me like he nailed him with a left first. I can’t be sure. And I don’t know how many times he hit him on the way down. Maybe six or nine times. Every one right on the mush. Hell, his fists were going so fast I couldn’t see them.”

The doctor jumped up into Freedon’s corner. Nat read his lips as he shook his head and said, “Broken jaw.”

Nat joined the shuffling crowd heading toward the exists. He picked up two boys he sometimes used, arranged with Lew Karon for the transfer of cash in some way that would not pain the Bureau of Internal Revenue boys by focusing their attention on it, and went back to the booth.

Garfield Tomlinson was there. There was relief on his face as he saw Nat February approach.

“Think I stood you up, uncle?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Half-Past Eternity»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Half-Past Eternity» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Half-Past Eternity» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)