On a more mundane level, there were bills from the hotel in Spindlermühle, as well as from the establishment where they later stayed in Holleschau itself. The former listed every item separately: cups of coffee and tea, even a glass of cognac, no doubt badly needed, as well as linens, and four candles, probably for placing by the head of the dead man as Jewish tradition required. A receipt from the Prager Tagblatt (the Prague Daily) dated 30 December indicated that the family must have listed their loss in the then equivalent of its ‘hatched, matched and dispatched’ column. Strikingly, the bill for 400 thank-you cards and envelopes was dated earlier, 28 December. Overwhelmed by the numerous letters of condolence with which they would have been inundated, the family must have turned their attention quickly to how they would manage to acknowledge them all. Each major expense was carefully recorded by Josef Redlich in a letter he later sent to his wife Sophie, who had followed her mother back to Berlin after the period of ritual mourning was over. It was on account of their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary that everyone had gathered in Moravia. But instead of celebrating, they, as the wealthiest members, seem to have marked the occasion by defraying the costs of this family tragedy. ‘My dear Sopherl,’ he wrote, before proceeding to detail the various amounts including both those for which he had receipts and those for which no acknowledgement could normally be expected. One of the more substantial items was the distribution of 400 kroner to the local poor, prior to the commencement of the funeral service.

It had been Rabbi Freimann’s wish that he be buried according to traditional rites and without undue fuss in the Jewish cemetery closest to the place where he died. In the event, he was interred in Holleschau, which probably wasn’t the nearest orthodox burial ground but lay close enough to Spindlermühle and recommended itself both because it had been the seat of his longest rabbinical incumbency and because his daughter and son-in-law still lived there and could take care of the practical arrangements and later look after the grave. At any event, his body was not taken back to Berlin; had he died there he would surely have been laid to rest in the Sonderfeld, the special section of the vast Weissensee cemetery. It was there, amid the elaborate memorial chambers, that some hundreds of Jews, the starving and spectre-like living dead, managed to conceal themselves from the Nazis among the tombs and mausoleaums of the blessed dead in their eternal peace.

Rabbi Freimann was laid to rest in Holleschau’s Jewish cemetery on 26 December 1937, on a freezing winter’s day, next but one to the grave of Rabbi Shabbetai Hacohen, known after his initials as the Shach, the illustrious commentator to the key sixteenth-century code of Jewish law, the Shulchan Aruch, and also a former leader of the local community, who had been buried there in 1663. One of Rabbi Freimann’s most important rabbinical tasks had been to deliver a learned lecture each year on the anniversary of the Shach’s death, in which he shared the latter’s teachings with the many scholars who came to visit his tomb. The field, with its tall gravestones and old funeral hall decorated with murals, remains undisturbed to this day.

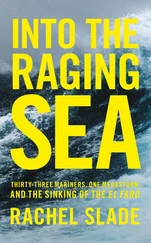

Many people from all around the world attended the funeral of Rabbi Freimann, that is, those who were able to get to Holleschau. The ceremony reflected the great love and high esteem in which this towering figure was held … The practice of all the traditional rites by the Chevra Kaddisha of Berlin, as well as the active participation of many rabbinical figures from our city, ensured that the parting from our teacher was conducted with due simplicity and ceremony.2

‘Those who were able to get to Holleschau’ included neither Rabbi Freimann’s older son Ernst, to whom the Nazis refused permission to leave Germany, nor his younger son Alfred, who observed the traditional mourning rites in Palestine together with the two of his sisters who by now also lived there. Regina would have been comforted by her other daughters, Trude and Sophie. Photographs shown to me by my father portrayed a long procession of men and women dressed in thick black coats and hats following the coffin on foot through the deep snow.

Ernst and his wife Eva wrote from Frankfurt:

It’s terribly hard that we’re not able to be with you. I had always believed that whatever happened we would be able to be together at once, but now there are mountains in between. Last time I parted from you, dear Mama, your heart was so heavy.

Did that final line indicate that Regina was well aware of the risk of a further stroke and afraid that something just like this might suddenly happen to her husband? Or was her mood occasioned by the terrible times?

Rabbi Jacob Freimann’s funeral procession outside the synagogue in Holleschau.

A few days later Ella, my grandmother, wrote from Jerusalem; she had been waiting to hear more about the funeral:

Dear Mama,

We still can’t comprehend the great misfortune which has overtaken us … We are constantly with you all in our thoughts. It’s a relief to know that Trude was with you, dear Mama. All through these days we’ve been longing for news from you. Of course you won’t be wanting to make any decisions right now, but it would be good if you would join us here in Jerusalem. Annchen wrote to us about how loving and attentive Sophie and Josef have been. This is a great comfort to us who are so far away.

A host of documents indicated that Regina spent much of the following months settling bills and dealing with the numerous administrative demands which follow any death, a painful task made all the more difficult by the hostile attitude which will have permeated most of the bureaucratic circles with which she had to deal. A copy of the will indicated that the couple had agreed that they would inherit each other’s possessions and that, upon the death of the second partner, their fortunes would be divided equally among their six children. On 14 February 1938 Regina had to declare for the purposes of any potential tax liabilities that they had six adult sons and daughters of their own and no further step- or adopted children. She was required to provide addresses for all of them, a circumstance which was to prove invaluable to me in attempting to uncover the traces of their lives seventy-five years later.

At the same time as she was coping with the paperwork resulting from her husband’s death, she also had to prepare a thorough inventory of her household possessions in readiness for shipping them to Tel Aviv, where, despite various hesitations, she hoped to go to escape Nazi Germany and rejoin the three of her children already in Palestine. Such lists were demanded by the Nazi authorities from anyone seeking to emigrate.

Amid all these pressing practical concerns Regina also had to make urgent decisions about her future. A letter to Alfred in Jerusalem from a family friend who was also a member of staff of the Palestine Office indicated that she was struggling to make up her mind what to do. That her preferred option was to go to Palestine was not in doubt. Her husband had firmly believed that God would redeem the divine promise and bring about the long-delayed return of the Jewish people to its ancestral land. But he was now dead and Regina had to face the future alone. The Jewish community agreed to forward her widow’s pension to Palestine if her application to emigrate were to prove successful, and the proposed sum of 350 Reichsmarks each month was generous. But what if the international situation should deteriorate still further and the transfer of monies became impossible? Would she then find herself penniless in a strange country, dependent on her family for support? Alfred’s correspondent observed that most people were happy just to get out of Germany alive and to leave worrying about what would happen afterwards until they knew that they were safe. But Regina was clearly concerned lest she prove a burden to her children who were all now struggling to establish a new life in challenging circumstances in a land full of conflicts of its own. The last thing she wanted was to become a source of trouble to her nearest and dearest.

Читать дальше