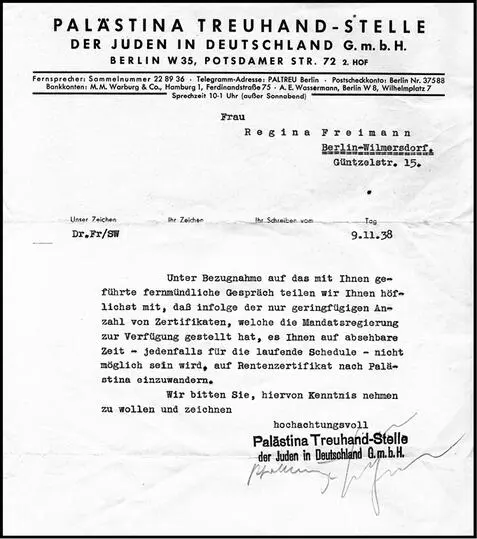

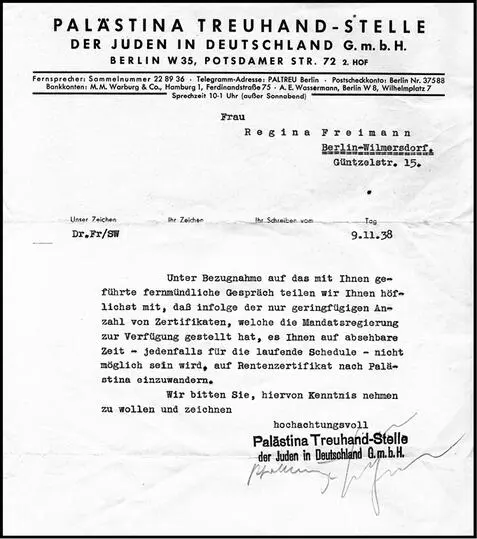

Letter to Regina Freimann from the Palästina Treuhand-Stelle.

The letter was sent from the offices of the Palästina Treuhand-Stelle der Juden in Deutschland, G.m.b.H (The Palestine Trust Company on behalf of the Jews of Germany Ltd). All applications for visas to Palestine had to be directed through its offices and were handled by its staff. They were expert not only in the intricacies of trying to leave Germany, but in the demands and conditions of the British Government which had effectively been ruling Palestine since 1918 under a United Nations mandate, due to expire in 1948. Beneath the stamp of the Palästina Treuhand-Stelle was an indecipherable signature, which only added to the bureaucratic impersonality of the message.

It was not an auspicious date on which to receive such news; the letter must have arrived in the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938). Now referred to in Germany as the Reichspogromnacht so as to avoid using the National Socialist expression, to most Jews this vicious and violent explosion will always be known as Kristallnacht (the Night of the Broken Glass), the date on which the true intent of the Nazi regime and its grip over the German and Austrian populations was revealed with a naked and grasping brutality which shattered irreparably the notion that life for the Jews could ever return to normal. Among the synagogues burnt down, Jewish premises destroyed and shops smashed and looted were the offices of the Palästina Treuhand-Stelle itself on the Meineckerstrasse. ‘In Berlin, 5, then 15 synagogues burn down. Now popular anger rages … It should be given free reign,’ Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister for Propaganda who was largely responsible for instigating the violence, recorded in his diary.1 The outburst, he explained, was simply the outpouring of the kochende Volksseele, a spontaneous expression of boiling popular feeling. He himself had given personal orders that the main Berlin synagogue on the Fasanenstrasse was to be destroyed. That night and over the following days tens of thousands of Jewish men were arrested and many murdered. It must have been a terrifying moment in which to learn that the key document on the obtaining of which one’s chief hopes of leaving Germany rested was not to be forthcoming.

I have held that letter in my hand and stared at it many times. For my great-grandmother, it amounted to a death warrant. This was not, of course, literally the case. But the rejection of her application by the Mandate authorities at that critical time led her to make practical decisions which, while perfectly rational and probably the best choices she could have made in the circumstances known to her at the time, would prove with hindsight to have sealed her fate. Three days later, at a meeting chaired by Hermann Göring, Reinhard Heydrich, then head of the Security Police and subsequently directly responsible for the policies which led to Regina’s murder, suggested that an agency be created under Nazi leadership to put into effect a nationwide policy to remove the Jews from the Reich. The chain of offices he created, with branches in Vienna and later in Prague with Adolf Eichmann at their head, would in fact lock the door against any chance of escape and rob hundreds of thousands of their possessions, hopes and lives. On the same day a fine of a billion marks was imposed on the Jewish community as punishment for the damage they had ‘caused’ on Kristallnacht.

In the event though, Regina was not at home in Berlin on the morning of 10 November. She was in fact in Frankfurt, helping her son Ernst and his wife Eva, who was in her ninth month of pregnancy with their fifth child.

When eventually Regina did open the letter she must have felt profoundly alone with the bad news. To whom could she turn? Whom could she phone to share the contents of that brief note and discuss what to do next? Among the papers in the bag I found in the old trunk were a number of telephone bills, but they carried no itemised list of calls or of the dates on which they were put through, so they were sadly of no use in discovering whether she still had a network of relatives and friends in the city. She may also have been aware that the phones were probably tapped and would have been cautious of sharing news over the telephone on such a delicate subject as emigration. The text of a telegram testified to her deep anxiety: ‘ Palästina-Amt total versagt. Hilfe dringend gebraucht ’ (‘the Palestine Office has let us down completely. Help urgently needed’). But the message wasn’t dated and was probably not her first, immediate response; it was sent by her and Sophie, her eldest daughter, together, and Sophie didn’t travel from Czechoslovakia to join her mother in Berlin until a few weeks later.

Of her six children, three had already fled Germany. Alfred, the youngest, was the first to leave, in 1933; Wally had followed him to Palestine in 1937. Ella, my grandmother, went later that same year. My grandfather, Robert, owned a timber mill in Rawitsch, a small town near Breslau. The city was the centre of one of the most swiftly Nazified regions in Germany and had a particularly vicious local leader. Tipped off by a German official that he was high on the Gestapo’s list, Robert took his family and fled the city that same night. ‘We laid the table as if we were planning to return very soon and packed just one small bag each so that nobody would be suspicious. Then we left for ever,’ my father recalled. He put the place so far behind him emotionally as well, at least at a conscious level, that he never, to the best of my memory, even mentioned to his children the address at which he had lived.

Regina’s other three children were still in Europe. Sophie had married and stayed in Holleschau, the small Moravian town where her father had served as rabbi for twenty years. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the First World War it became part of Czechoslovakia and was renamed Holešov. Trude lived in Poznań, the second of Jacob Freimann’s major rabbinical positions. Ernst, the only other son, a doctor in Frankfurt-am-Main, was closest in distance to Berlin. But, thanks to the Gestapo, he was in no position to help his mother. In fact, Regina, a pious and selfless woman whose first thoughts were always for her family, was almost certainly much more worried for Ernst and his wife and children than she was about herself.

More than anyone, though, Frau Dr Regina Freimann, as she was formally addressed on the envelopes of the letters, must have missed the presence of her husband. It was less than twelve months since he had died, suddenly, on 23 December of the previous year, while they were travelling to celebrate Sophie’s twenty-fifth wedding anniversary in Czechoslovakia. He had been suffering from high blood pressure for a number of years and had already experienced several strokes. He was taken ill while on the train and died in the early hours of the following day in a hotel in the mountain resort of Spindlermühle.

A separate bundle inside the bag in the trunk contained letters and receipts pertaining to his funeral. Throughout 1938 Regina naturally remained preoccupied not only with the emotional but also with the practical aftermath of her husband’s death. She had carefully kept all the relevant papers. A bill for two night-time visits showed that the local physician, Dr Franz Kindler, had twice been in attendance. There had evidently been nothing he could do to save the ailing rabbi’s life. It may indeed have been a mercy that death came swiftly. A quote from Gustav Fischer’s funeral services, based in Hohenelbe in the mountains of northern Czechoslovakia, itemised the expenses involved in the collection and transportation of the body, including the price of the coffin, the cost of procuring essential documentation, and smaller amounts for sundry telephone calls and telegrams. There were bills and receipts from the Burial Society and the Jewish Community of Holleschau, who provided the plot in the cemetery and supervised the actual funeral. A separate invoice from Leo Klein of the same town showed that there had been five Sterbe-Wäscher (washers of the dead), members of the Sacred Society privileged with the task of conducting the ritual preparation of the body and dressing it in the plain white linen vestments in which Jews are traditionally buried. A further list gave the costs of these garments, as well as of the sheets in which the body was cleaned and dried.

Читать дальше