Tolstoy’s presence in the text is felt everywhere, but especially in his use of the parenthetical aside, whereby the authorial voice suddenly and unashamedly disrupts the story to offer a comment or explanation, revealing a contempt for the very artifice of fiction with which it is beguiling us. In the Russian, this change of voice mid-dialogue carries no warning punctuation, but in the translation it is isolated by the usual marks. In this, as in so many other respects, Tolstoy’s virtuoso brilliance prefigures the modernists of the twentieth century: Vladimir Nabokov, for example, writing in English almost a hundred years later, would perfect the art of parenthesis with his famous: ‘(picnic, lightning)’, but well before that Joseph Conrad and Virginia Woolf were just two among the many whose admiration had taken the sincerest form it could, that of imitation. The present translation has tried to convey some of the special qualities that make this early version of War and Peace, written with the energy of an artist who was still feeling his way to greatness, so deserving of our close attention.

Jenefer Coates

Editor

Andrew Bromfield

Translator

Table of Russian Weights and Measures

Approximate equivalents of old Russian measurements:

| arshin = 28 inches |

or |

71 cm |

| desyatina = 3.6 acres |

or |

1.45 hectares |

| pood = 36 lbs |

or |

16 kilograms |

| sazhen = 7 feet or 2.3 yards |

or |

2.1 metres |

| vershok = 1.75 inches |

or |

4.5 cm |

| verst = 2/3 or .66 mile |

or |

1 kilometre |

Leo Tolstoy. Photograph, Moscow 1868.

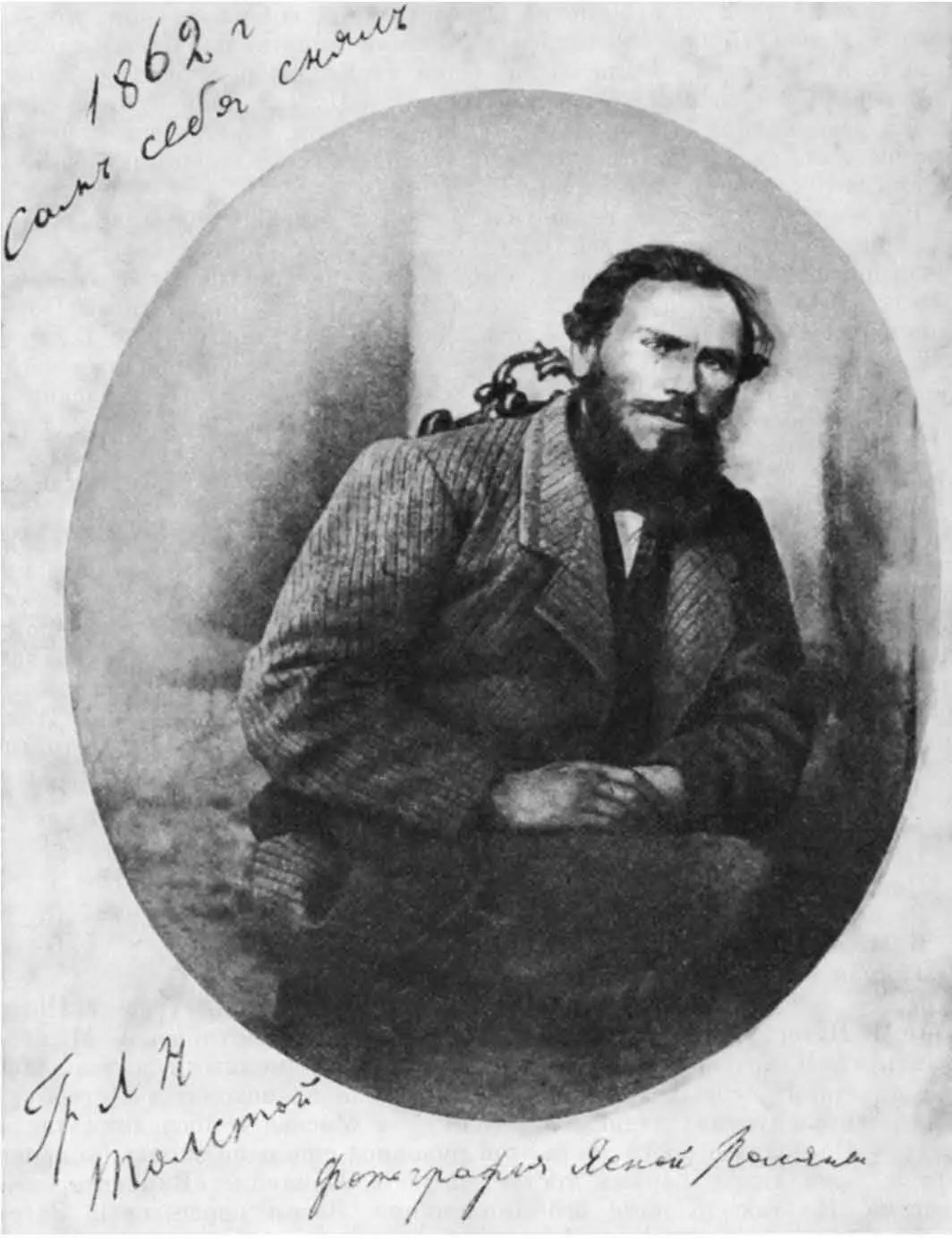

Tolstoy. Photograph, 1862.

Prince Vasily. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

The Little Princess. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Pierre Bezukhov. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Hippolyte Kuragin. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Pierre Bezukhov. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Dolokhov’s Wager with the Englishman. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Sonya. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Natasha Rostov and Boris Drubetskoy. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Princess Anna Mikhailovna Drubetskaya and her son Boris. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Dancing the Daniel Cooper. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

The Death of Count Bezukhov. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

The Struggle for the Document Case. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

The Maths Lesson. Wood engraving by K.I. Rikhai after the drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1866.

Kutuzov. Engraving by Cardelli.

The Military Review: Kutuzov and Dolokhov. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1867.

Russian Army Marching Across the River Enns. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1867.

Napoleon in 1807. Engraving by Debucourt.

Bilibin. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1867.

Prince Andrei and Emperor Franz. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1867.

Wounded Rostov at the Campfire. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1867.

Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805. Engraving by Bosque after the drawing by Charles Vernet.

The Meeting of the Two Emperors at Tilsit on 25 June 1807. Engraving by Couché fils after the drawing by Zwiebach.

Natasha Dancing at the Uncle’s House. Drawing by M.S. Bashilov, 1860s, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Smolensk, 20 August 1812. Lithograph.

The Battle of Borodino. Lithograph by Albrecht Adam.

A sheet of Manuscript 107.

Final sheet of Manuscript 107: “The End”.

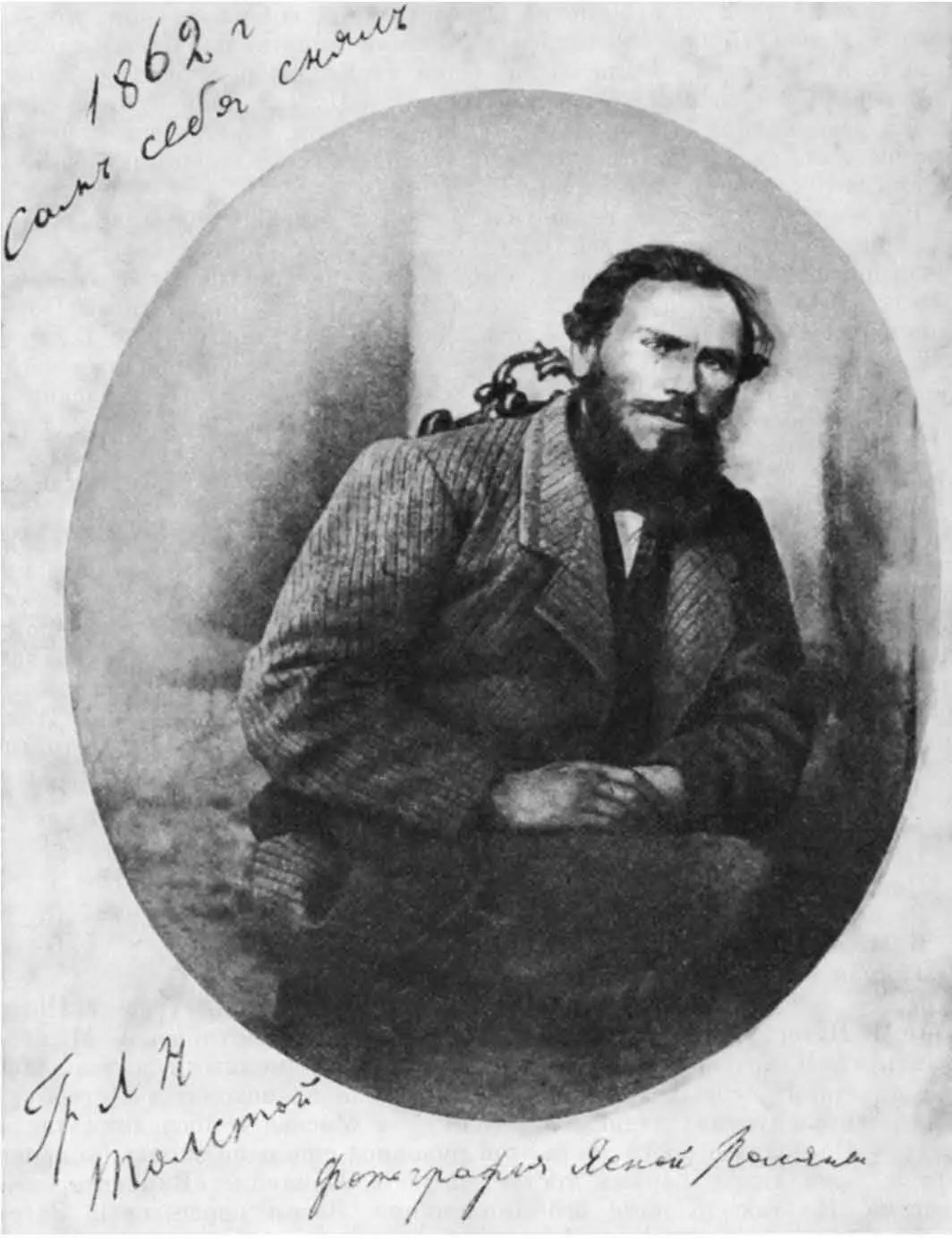

TOLSTOY Photograph 1862 Autograph on mounting: “1862. I took this myself. Count L.N. Tolstoy. Photograph at Yasnaya Polyana.”

“Eh bien, mon prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now merely estates, the private estates of the Buonaparte family. Non, I warn you, if you don’t say this means war, if you still defend all these vile acts, all these atrocities by an Antichrist (for I really do believe he is the Antichrist), then I no longer know you, you are no longer mon ami, you are no longer, as you put it, my devoted slave. But, anyway, how do you do, how are you? I see I am frightening you, do come and sit down and tell me what’s going on.”

These were the words with which, in July 1805, the renowned Anna Pavlovna Scherer, lady-in-waiting and confidante of the Empress Maria Fedorovna, greeted the influential and high-ranking Prince Vasily, who was the first to arrive at her soirée. Anna Pavlovna had been coughing for several days, and had what she called the grippe (grippe then being a new word, used only by the few), and therefore had not attended at court nor even left the house. All of the notes she had sent out in the morning with a scarlet-liveried servant had contained the same message, without variation:

If, Count (or Prince), you have nothing better to do, and the prospect of an evening in the company of a poor invalid is not too alarming, then I should be delighted to see you at home between seven and ten o’clock.

Annette Scherer.

“Dieu, what a fierce attack!” replied the prince with a faint smile, not in the least perturbed by this reception as he entered, wearing his embroidered court dress-coat, with knee-breeches, low shoes and starry decorations, and a serene expression on his cunning face.

He spoke that refined French in which our grandfathers not only spoke, but also thought, and with the gently modulated, patronising intonation that was natural to a man of consequence who had grown old in society and at court. He went up to Anna Pavlovna and kissed her hand, presenting to her the bald, perfumed top of his head, which gleamed white even between the grey hairs, then he calmly seated himself on the divan.

“First of all, tell me how you are feeling, ma chère amie? Do set your friend’s mind at rest,” he said, without changing his tone of voice, in which, beneath the decorum and sympathy, there was a hint of indifference and even mockery.

“How can you expect me to feel well, when one is suffering so, morally speaking? How can anyone with feeling stay calm in times like these?” said Anna Pavlovna. “You are here for the whole evening, I hope?”

“But what about the festivities at the English ambassador’s? Today is Wednesday. I really do have to show my face,” said the prince. “My daughter will be calling to take me there.”

“I thought today’s celebrations had been cancelled. I do declare all these fêtes and fireworks are becoming an utter bore.”

“Had they but known you wished it, they would have cancelled the celebrations,” said the prince by force of habit, like a wound-up clock, voicing things that he did not even wish to be believed.

“Don’t tease me. Eh bien, what has been decided following this dispatch from Novosiltsev? You know everything.”

“What can I say?” the prince said in a cold, bored voice. “What has been decided? It has been decided that Buonaparte has burnt his boats, and we are apparently prepared to burn ours too.”

Whether Prince Vasily’s words were wise or foolish, animated or indifferent, he uttered them in a tone that suggested he was repeating them for the thousandth time, like an actor speaking a part in an old play, as though the words were not the product of his reason, not spoken from the mind or heart, but by rote, with his lips alone.

Читать дальше