William and Dorothy united their fates against great practical, cultural and familial odds. Their falling in love with each other was not just a transformation of the heart. It involved a revolution against everything they had been bred to be, challenging the blind duty of children towards their parents, the pecuniary aspect of marriage and the inferiority of women in their relations with men.

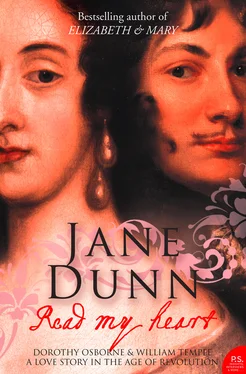

Dorothy was intellectual, self-contained and enigmatic, her dark-eyed beauty perhaps inherited, along with her forthright character, from her Danvers grandmother, who the biographer John Evelyn claimed had Italian blood. William was even more conventionally good-looking; in Dorothy’s own words, ‘a very pritty gentleman and a modest [one]’. 21 According to his sister his luxuriant dark brown hair ‘curl’d naturaly, & while that was esteem’d a beauty nobody had it in more perfection’. 22 In an age of shaved heads and extravagant wigs, he wore his own hair long and unpowdered. He was tall and athletically built and overflowing with a breezy energy and enthusiasm that attracted everyone. Dorothy’s seriousness of mind would deepen his character while his own ‘great humanity & good nature, takeing pleasure in makeing others easy and happy’ 23 brought warmth and optimism to a woman who felt keenly the darker side of life. ‘I never apeare to bee very merry, and if I had all that I could wish for in the World I doe not thinke it would make any visible change in my humor,’ 24 was how she explained her naturally pensive, even sorrowful, expression.

Their stolen month of ecstatic discovery was brought to an abrupt end. Sir John Temple had learned with irritation that his son had barely travelled beyond the English shores; his irritation became alarm when he heard ‘the occasion of it’: his son’s delight in an impoverished young woman. He issued the stern parental order to depart to Paris without delay. This was an age when even grown children expected to obey their parents absolutely and in this William conformed immediately. Both he and Dorothy would continue to honour their parents’ wishes, even when they ran diametrically opposed to their own, although through evasion and covert rebellion they managed not always to comply. There were crucial material, social as well as moral imperatives for filial duty and both Temple and Osborne fathers intended to enforce them. For Dorothy and William to marry without family support meant a precipitous plunge into poverty as family money was withheld; and with the debilitating loss of social status came diminished opportunities for suitable employment. However, much as both families disliked the idea of love entering marriage negotiations and obstinately continued to frustrate this renegade plan, the subversive lovers made a private commitment to each other while in St Malo and trusted they might have a future together some day.

Looking back on their lives, William’s sister had thought his and Dorothy’s courtship was as good a love story as any fiction and that their letters should have been published as a ‘Volum’. ‘I have often wish’d the[y] might bee printed,’ she wrote, and even though she thought her brother’s writings exceptional it was Dorothy’s letters that she particularly admired: ‘I never saw any thing more extraordinary then hers.’ 25 This call for their publication was a radical statement at the time. It was perhaps a measure of how highly esteemed Dorothy’s letters were, even by contemporaries, that Martha could envisage personal love letters from a woman to a man, to whom she had been forbidden to write and had yet to marry, could ever properly be published when such exposure was considered unwomanly, or worse. The extreme vicissitudes of their love affair were recognised by everyone who knew them, and most acutely by Dorothy and William themselves, as making their story akin to the best fictional romances where true love was thwarted at every turn until the final satisfying embrace.

No letters survived from this first stage of their separation but both refer to this period in other contexts. In the following two to four years William re-wrote romances from the French * and amplified them for his own and Dorothy’s enjoyment. He also used the dramas to work out his own youthful thoughts and feelings on the conundrums of human experience and to distract him from his own unhappiness at being forcibly separated from the woman he loved. They were an outlet too for his frustrated desires, a proxy voice for feelings he was unable to express to her in person: ‘a vent to my passion, all I made others say was what I should have said myself to you upon the like occasion’. 27 He revealed just how much she haunted him: ‘[I] shewd you a heart wch you have so wholly taken up that contentment could nere find a room in it since first you came there.’ 28 William told Dorothy they were meant to be read as letters from him to her.

A letter composed by William and introduced into the plot of one of these romances, The Constant Desperado , spoke directly to her alone, he declared, the more passionate the feeling, the more personally it was written for her: ‘you will find in this a letter that was meant to you though nere superscribd, and bee confident whatever in it is passionate said twas you indited [it was composed for you].’ 29

Embedding his messages in the overheated atmosphere of a French romance also gave William a means of communicating intense emotion and dramatic declarations without embarrassment. Despite some hyperbole necessary for the genre, his sense of loss and despair in being separated from Dorothy was real and direct and expressive of his own youth and overflowing feelings. It also gave an insight into her conversations with him before he left on his journey, when she feared most that his declarations of love were just airy confections and would disperse on the wind:

Madam

I count all that time but lost which I liv’d without knowing you … Tis impossible to tell you how often I have died since I left you, for I have done it as often as I have thought of you, and thought of you as often as I have breath’d; you thinke it strange that I am dead and yet have motion enough to write, alas (Madam) though I am dead, my passion lives, and tis that now writes to you, not I; have I not often told you that would never dye? And as often I could never outlive the losse of your sight; you at first thought them winde like other words, and they would soone blow over, but learne (Madam) a lovers heart is allwayes at his mouth when his Mistresse is neere him … for all this[,] dead as I am[,] if my hopes are not so too, and there are any of seeing you, methinks your eyes would revive mee … Let me know by your letters you remember mee, if you would not have mee dye beyond all hopes of a resurrection. 30

In writing these personalised romances for Dorothy, William was also setting himself up in competition with the French writers she so much esteemed. Throughout their courtship she urged the turgid volumes upon him, begging him to read them too so that she could discuss character and motivation with him. Here he was attempting a pre-emptive strike, hoping perhaps that she would rate his work as highly as theirs, or at least see him in an enhanced light. His romances also pursued certain philosophical and moral arguments that suggest something of their youthful discussions, as well as the surge of emotion that overcame them both during their transfiguring month in St Malo.

In speaking of the hero of one of his stories, William amplified his country pursuits into allegories on life itself. Here he appears to acknowledge that his newfound love also brought danger; the greater the ecstasy the more painful the loss. In love, he was now no longer safe and self-contained and his carefree days were over:

sometimes he flies the tender partridge, others the soaring hearne [heron] and his hawkes never missing, hee concludes that fly wee high or low wee must all at length come alike to the ground; if there bee any difference that the loftier flight has the deadlier fall. sometimes with his angle hee beguiles the silly fish, and not without some pitty of theire innocence, observes how theire pleasure proves theire bane and how greedily they swallow the baite wch covers a hooke that shall teare out theire bowels, hee compares lovers to these little wittlesse creatures, and thinks them the fonder [more foolish] of the two, that with such greedy eyes stand gazing at a face, whose beguiling regards will pierce into theire hearts, and cost them theire freedome and content if they scape with theire lives. 31

Читать дальше