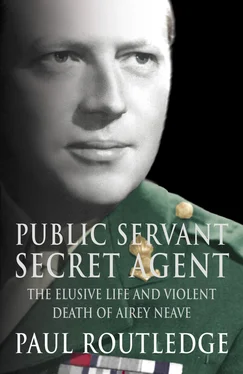

PUBLIC

SERVANT,

SECRET

AGENT

The Elusive Life and Violent Death of Airey Neave

Paul Routledge

Cover

Title Page PUBLIC SERVANT, SECRET AGENT The Elusive Life and Violent Death of Airey Neave Paul Routledge

Preface

1 The Price of Liberty

2 Origins

3 King and Country

4 Capture

5 Colditz

6 Escape

7 Operation Ratline

8 Secret Service Beckons

9 Enemy Territory

10 Nuremberg

11 Lawyer Candidate

12 The Greasy Pole

13 Locust Years

14 A Very Spooky Coup

15 In the Shadows

16 Plotting the Kill

17 Pursuit and Retribution

18 The End of the Trail

References

Index

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

A gun lay unobtrusively on the settee beside my polite host, and the heavily-built man sitting on an armchair in the corner wore a tight-fitting black mask with tiny holes for his eyes and mouth. He was on edge and there was a tension in the room. I had come a long way, physically and in time, to see the killers of Airey Neave, and here I was, face to face. Not with the men who planted the bomb on 30 March 1979, almost twenty-two years ago to the day, but with ‘someone connected with the Neave operation’ who belonged to the small but highly dangerous Irish National Liberation Army.

The trail started five years earlier, when I was writing a biography of John Hume, leader of the SDLP, a shrewd nationalist and a rock for thirty years in the maelstrom of Irish – and British – politics. Hume crossed paths with Neave, the Conservatives’ Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary, many times during the late 1970s. It was not a profitable relationship. Hume found Neave’s traditional Tory attitudes towards Ulster Unionism and his militarist stance on the Troubles short-sighted and unsophisticated. Neave probably thought the former trainee priest slippery and threatening. He had, after all, engineered the short-lived exercise in political power-sharing that the Tory spokesman on Ulster utterly rejected.

Neave’s impact on policy towards Northern Ireland during the four years he held the Shadow portfolio was limited, but his death at the hands of terrorist assassins in the precincts of the House of Commons convulsed politics and prompted the question in my mind: ‘Who was this man?’ There was no biography of Airey Neave, yet he had lived an eventful life. Eton, Oxford and the Inns of Court were followed by capture in the siege of Calais, prison camps, escape from Colditz and service in military intelligence. He had served the indictments on Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg and entered Parliament at his third attempt in a by-election. A promising ministerial career was cut short by a heart attack, and he seemed destined to live out his political career in back-bench obscurity until the social upheavals of the 1970s propelled him into history as the man who gave us Margaret Thatcher.

It was a remarkable story, but no one had written it. I therefore resolved to do so and began collecting material. It was clear from the outset that Neave’s family (his daughter Marigold and two sons, Patrick and William) were apprehensive about the project. Neave had not wanted a biography, beyond the books he had written about his life, nor did his widow, Diana, who died in 1992. Other approaches, I knew, had been rebuffed and I was hardly the writer of choice. Yet I persisted and the family finally agreed to cooperate, though not on a lavish scale.

Much more difficult was ‘the other side’ – the perpetrators of the murder. Over the years reporting from Ulster, through a republican contact I will not name, I had learned something of the Irish Republican Socialist Party, the political wing of INLA. After an initial social meeting in a Belfast bar, at which I outlined my intentions, I let the seeds germinate. Then, in the autumn of 2000, I approached the IRSP directly, and arranged to visit the party’s headquarters in the Falls Road, the heart of republican Belfast. The taxi driver who took me there on 17 November advised against going into the pub opposite. ‘Not with your accent [Yorkshire],’ he grinned. Seamus Costello House, a large red-brick villa (allegedly bought with the proceeds of a bank robbery) is protected by steel mesh fortifications. A photographic tableau of the dead hunger strikers stands outside. Inside, the atmosphere is more homely, reminiscent of an old-fashioned trade union branch office, with people asking for advice and children playing about their mothers’ knees. Banners and framed slogans decorate the walls. The furniture is utilitarian. Everyone smokes.

Paul Lyttle, the IRSP’s spokesman, listened courteously to my pitch. It was clear from the first that my credentials had already been thoroughly checked. They knew who I was and where I was coming from before I opened my mouth. So, indeed, did the security services. This visit was known in London before I returned the following day. I told Lyttle that I wanted to write an account of Neave’s death that was as authentic as possible. To that end, I wished to meet the killers, if possible; and if that could not be arranged, then to talk to INLA ‘volunteers’ involved in the operation. There had been many accounts of the assassination, mostly conflicting. Was it not now time for the truth?

The door seemed to be ajar. The IRSP man dwelt on the dangers that Neave presented to militant republicanism, being one of the few British politicians who (as an ex-POW) knew just how critical was the morale and organisation of ‘the men behind the wire’. However, those men had virtually all been released under the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and yes, the organisation might be willing to brief me. A decision would have to be taken by ‘the executive’, and this process would take some time. It was also plain that the IRSP/INLA felt that the assassinations of four of their top people in the aftermath of Neave’s death should receive the same kind of public scrutiny currently being given by the Savile Enquiry to the killings on Bloody Sunday in Londonderry in January 1972. I said I had no difficulty in understanding their desire to get to the bottom of these high-profile murders, which were widely laid at the feet of the security services working through loyalist proxies. And I would say as much, though I fear the party’s demands for a similar public enquiry will fall on deaf ears.

Weeks passed, and after Christmas I wrote again to the IRSP, pointing out my approaching deadline for completion of the book. I also telephoned regularly, not a simple procedure. Seamus Costello House is not Millbank or Central Office. Finally, I was given a number to contact in the Irish Republic. It was a mobile, not reachable from London. Further frustrating delays followed before I got through to a man I will refer to as Eoin. He told me to go to Belfast on the weekend of 24 March, and get in touch again on Friday 23rd. On Thursday, I received a message to call him again, and was redirected to Cork, hundreds of miles to the south in the Republic. It was too late to book a direct flight, so I continued via Belfast on the 23rd. Foot and mouth disease had just broken out in County Louth, slowing the train journey to Dublin, but I reached Cork in the early evening.

My instructions were to book into the Silver Springs Hotel, a modern establishment a few miles south of the city, and to await a call the following day. It was a bright, clear morning and the telephone rang at 9.30 a.m. I was to take a taxi to a country pub about five miles away, where I would be met. I waited in the lobby, self-consciously British in a dark suit and university tie. Just after 10.00 a.m., two men entered and motioned me into the bar. One was young, in his twenties, powerfully-built and dressed in waxed jacket and jeans. The other was much older, with white hair. Waxed-jacket said: ‘We will take you in the car. You will not look at the number plate. You will look down at the floor, not where we are going. Understand?’ I did. He then asked if I had a mobile phone, and I fished mine from a travel bag thinking he wished to use it. He confiscated the instrument.

Читать дальше