Outside, he stood guard so I could not see the number plate. The older man drove, through various country lanes. It was difficult to obey the injunction to stare at the floor, but since I had no idea where we were it seemed superfluous anyway. We stopped outside an isolated house, quite high up, with hills around. I was escorted into the front room, where the thick curtains were drawn. Eoin, now that I saw him, looked like a schoolteacher in his late thirties: neat, spare and casually but well dressed. He introduced the man in the mask as ‘someone directly involved in the Neave operation’. I asked if I could take a shorthand note and he nodded. ‘You’re not wired?’ he interjected suddenly. ‘Open your shirt.’ I unbuttoned my shirt to the waist to show there was no hidden microphone. He frisked me, arms, back, front and legs. The tension eased somewhat, though I then spotted the handgun next to him. Had I done anything silly, I think it would have been used.

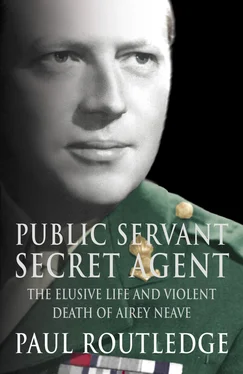

However, coffee and biscuits were served, as though we were discussing details of the Easter holidays rather than the brutal murder of a British politician two decades earlier. We spoke for two and a half hours, a mixture of questions and volunteered statements. The man in the mask, who displayed a very detailed knowledge of bomb-making and the modus operandi of the assassination, occasionally tugged at his uncomfortable camouflage. Eoin, the more intellectual of the two, ranged across the whole subject of INLA, the armed struggle and prospects for the future. It was a fascinating, if eerie, dialogue. What follows in Chapter 18 is a distillation of that briefing. I believe it to be the most authentic account yet of the circumstances of Airey Neave’s death. I expect that others may contest this assessment, but I am convinced that the IRSP/INLA deliberately gave this briefing to ensure that the truth is established, not least because they want the truth about the killing of their own.

At the close of the meeting, my mobile phone was returned, with the SIM card disabled so I could not be traced. The white-haired driver took me to a shopping centre, where I took a taxi back into Cork city to take the train to Dublin and Belfast. I drank a pint of Guinness at the station and pondered my experience. Instead of a reporter’s elation at finding my quarry, I felt a curious unease, as though I had discovered something I would rather not have known. Yet there was no going back, and I turned for home with a determination to get all this out. I hope the succeeding pages will demonstrate the virtue of seeking the truth, unpalatable though it may be. The Irish Question is never going to be solved by meek acceptance of the official line.

It should be added that this biography is not authorised, nor did I seek authorisation. Neave had written much about his own life, but his widow Diana rejected writers’ advances to sanction a biography of her husband. Patrick Cosgrave, a family friend, said she had asked him ‘to spread the word among the writing classes that she would, in no circumstances, countenance such a project’. Plainly, we do not move among the same writing classes because no such word reached these quarters.

However, I was able to speak to Neave’s children, Marigold, Patrick and William, for which I am grateful. I would also like to thank his cousin Julius Neave, of Mill Green House, Ingatestone. My gratitude also goes to Toni Luteyn, Neave’s co-escaper from Colditz, still alive and well in The Hague; to Frau Lipmann, curator of Colditz Museum; to the dedicated staff at the unrivalled political history collection at the Linen Hall Library for their help and advice; to the librarians at Eton College and Merton College, Oxford; to my colleagues in Westminster, especially Desmond McCartan, formerly of the Belfast Telegraph and David Healy of Bloomberg Agency; to Colin Wallace, Brian Crozier, Gerald James, Michael Elliott, Kevin Cahill, Roger Bolton, Richard Dumbreck, Sir Edward du Cann, Sir William Shelton, Tam Dalyell, Lord Lawton, Lord Campbell of Alloway, Ken Lockwood of the Colditz Association, Steven Norris, Kevin Macnamara MP, and those in London and Belfast who would be embarrassed (or worse) if identified; to Clive Priddle, Mitzi Angel and Kate Balmforth at Fourth Estate for their patience, and Richard Collins for his professional copy-editing; to my agent Jane Bradish-Ellames and finally to my wife Lynne for living with a political murder for too many years.

Walworth, south London

November 2001

At 2.58 p.m. on 30 March 1979 an enormous explosion shook New Palace Yard in the precincts of the Palace of Westminster. Seconds later, smoke was seen billowing from the wreckage of a saloon car on the ramp leading up from the MPs’ car park into the cobbled courtyard just below Big Ben.

The blast was heard in the Commons chamber, where parliament was about to be dissolved for a General Election that would sweep Margaret Thatcher into Downing Street. Policemen and parliamentary journalists rushed to the scene and found an unidentifiable man, dressed in the black coat and striped trousers of an old-fashioned style still worn by Conservative MPs. David Healy, political correspondent of the Press Association news agency, was in the third-floor Press Gallery bar, whose back windows look down on New Palace Yard. A veteran reporter of the Irish Troubles, Healy recognised the familiar noise. ‘I knew it was a bomb,’ he said. ‘I looked out of the window and saw smoke, and rushed downstairs. The car was burning, the windows all broken. And this guy was almost blown into a standing position behind the wheel. A cop shouted, “He’s still alive! Clear the area!” I didn’t think there was much life left in him. I couldn’t tell who it was, though I had been having a drink with him only two nights earlier.’ 1 Another Westminster lobby correspondent, Desmond McCartan of the Belfast Telegraph , who knew the victim well, wrote: ‘The blackened, bleeding features amid the tangled wreckage of his Vauxhall car concealed his identity, but the pain of his dying was clear.’ 2

Ambulancemen who arrived within minutes found the still unidentified figure slumped over the driving wheel, his face blackened, his hair and clothing charred from the blast. His right leg was blown off below the knee, and his left leg was almost completely severed. One ambulanceman, Brian Craggs, tried to give him oxygen: ‘He was still breathing, but was very badly injured. He never regained consciousness.’ A doctor and nurse also attended, before he was freed after half an hour of frantic effort by firefighters.

Others had also recognised the noise. In Margaret Thatcher’s office, Chris Patten, a future Northern Ireland minister, exclaimed ‘That was a bomb!’ Thatcher’s entourage witnessed the grim scene from an upstairs window and Guinevere Tilney, wife of a former Tory MP and adviser to the Conservative leader, was the first to discover the identity of the victim. In the car, dying, lay Airey Neave, Conservative MP for Abingdon, war hero and habitué of the murky world where the politics of democracy and the secret state intertwine, the man who had engineered Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power. Mrs Tilney immediately went to the Neave family flat in Marsham Street to tell his wife Diana, and took her to Westminster Hospital where Neave was undergoing emergency surgery. The surgeons could do little. His heart stopped on the operating table and he died eight minutes after arriving at the hospital. His devoted wife was too late to see him alive.

It was a bloody end to a long career in public life, one marked in turn by disappointment and triumph ultimately crowned by Neave’s brilliant campaign to secure the Conservative Party leadership for Margaret Thatcher, an event that would radically change British – and international – politics. For his key role in that crusade, Neave was rewarded with the Shadow Cabinet portfolio that he coveted: Northern Ireland. It was a strange post to covet. Ulster has traditionally been regarded by pundits as a graveyard for political ambition, and Neave was fifty-nine when he took on the job in February 1975, having hitherto shown no serious public interest in the issue.

Читать дальше