KATHRYN HUGHES

The Short Life & Long Times of Mrs Beeton

For my parents, Anne and John HughesAgain, again

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

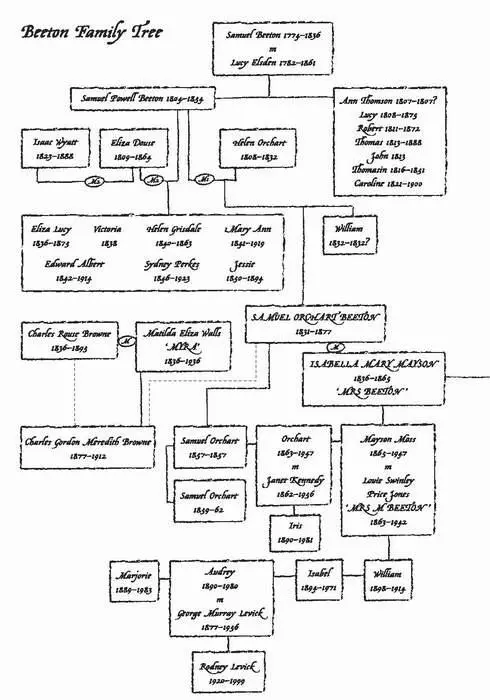

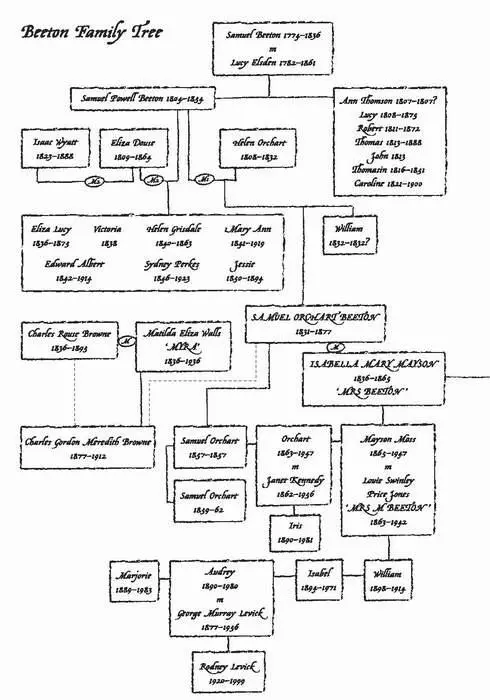

Family Trees

PROLOGUE: ‘A Tub-Like Lady in Black’

CHAPTER ONE: ‘Heavy, Cold and Wet Soil’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER TWO: ‘Chablis to Oysters’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER THREE: ‘Paper Without End’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER FOUR: ‘The Entire Management of Me’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER FIVE: ‘Crockery and Carpets’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER SIX: ‘A Most Agreeable Mélange’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER SEVEN: ‘Dine We Must’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER EIGHT: ‘The Alpha and the Omega’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER NINE: ‘Perfect Fashion and Elegance’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER TEN: ‘Her Hand Has Lost Its Cunning’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER ELEVEN: ‘Spinnings About Town’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER TWELVE: ‘The Best Cookery Book in the World’

INTERLUDE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: ‘A Beetonian Reverie’

NOTES AND SOURCES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

P.S.

About the Author

Q and A with Kathryn Hughes

Life at a Glance

A Writing Life

Top Ten Favourite Books

About the Book

On the Beeton Track by Kathryn Hughes

Read on

Have You Read?

If You Loved This, You Might Like …

Find Out More

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE ‘A Tub-Like Lady in Black’

ON BOXING DAY 1932 the National Portrait Gallery opened an exhibition of its new acquisitions to the public. There were twenty-three likenesses on display, all of which were to be added to the nation’s permanent portrait collection of the great and the good. Cecil Rhodes, ‘South African Statesman, Imperialist and millionaire’, was one of the new arrivals, as was the Marquis of Curzon, who had until recently been Conservative Foreign Secretary. By way of political balance there was also a portrait of James Keir Hardie, the first leader of the Labour Party in the House of Commons, and a replica of Winterhalter’s magnificent portrait of the Duchess of Kent, Queen Victoria’s mother. Oddly out of place among the confident new arrivals, all oily swirls, ermine, and purposeful stares, was a small hand-tinted photograph of a young woman dressed in the fashion of nearly a hundred years ago. She had a heavy helmet of dark hair, a veritable fuss of brooch, handkerchief, neck chain, and shawl, and the fixed expression of someone who has been told they must not move for fear of ruining everything. The caption beneath her announced that here was ‘Isabella Mary Mayson, Mrs Beeton (1836–65)’, journalist and author of the famous Book of Household Management .

By the time the first members of the public filed past the photograph of Mrs Beeton on Boxing Day, her biographical details had already changed several times. Sir Mayson Beeton, who had presented the photograph of his mother to the nation nine months earlier, had insisted on an exhausting number of tweaks and fiddles to the outline of her life that would be held on record by the gallery. Even so, Beeton was still disappointed when he attended the exhibition’s private view a few days before Christmas. Particularly vexing was the way that the text beneath his mother’s photograph described her as ‘a journalist’. Beeton immediately fired off a letter to the curator, G. K. Adams, suggesting that the wording should be altered to ‘Wife of S. O. Beeton, editor-publisher, with whom she worked and with the help of whose editorial guidance and inspiration she wrote her famous BOOK OF HOUSEHOLD MANAGEMENT devoting to it “four years of incessant labour” 1857–1861’ – a huge amount of material to cram onto a little card. The reason Sir Mayson wanted this change, explained Adams wearily to his boss H. M. Hake, director of the gallery, was that ‘he said his father was an industrious publisher with a pioneer mind, who edited all his own publications, and but for him it is extremely unlikely that Mrs Beeton would have done any writing at all’.

Mayson Beeton was by now 67 and getting particular in his ways. Even so, he had every reason to fuss over exactly how his parents were posthumously presented to the nation. Over the six decades since their deaths Isabella and Samuel Beeton had all but disappeared from public consciousness. The Book of Household Management was in everyone’s kitchen, but most people, if they bothered to think about Mrs Beeton at all, assumed that she was a made-up person, a publisher’s ploy rather than an actual historical figure. Almost worse, from Mayson Beeton’s point of view, was that virtually no one realized that it was Mr, rather than Mrs, Beeton who had coaxed the famous book into being. Its original name, after all, had been Beeton’s Book of Household Management and there was no doubt about which Beeton was being referred to.

Getting the presentation of his parents just right had become an obsession with Mayson Beeton, whose birth in 1865 had been the occasion of his mother’s death. Only the previous year an article had appeared in the Manchester Guardian that managed to muddle up Mrs Beeton with Eliza Acton, a cookery writer from a slightly earlier period. Beeton’s inevitable letter pointing out the error was duly published, and from these small beginnings interest in the real identity and history of Mrs Beeton had begun to bubble. In February 1932 Florence White, an authority on British food, had written a gushy piece in The Times entitled ‘The Real Mrs Beeton’ which drew on information provided by Sir Mayson to paint a picture of a ‘lovely girl’ who enjoyed the advantages of ‘YOUTH, BEAUTY, AND BRAINS’. Mrs Beeton, it transpired, was a real person – albeit a rather two-dimensional one – after all.

H. M. Hake had happened to read White’s piece in The Times and was struck by her reference to the family owning ‘portraits’ of Mrs Beeton and wondered if there might be something suitable to hang in the National Portrait Gallery. The answer, when it came back, was disappointing. There was no portrait of Mrs Beeton, just a black and white albumen print, taken by one of the first generation of High Street photographers, probably in the early summer of 1855 when she was 19 years old. It had subsequently been hand-tinted by one of Sir Mayson’s daughters, giving it a cheap, chalky finish. This was not the kind of flotsam that the National Portrait Gallery usually bothered itself with. Still, the times were changing and it was important to change with them. After a consultative meeting on 7 April 1932 the trustees decided that they were prepared to accept, for the first time in their history, a photographic portrait to hang among their splendid oils and marble busts.

That the trustees of the National Portrait Gallery decided to hang Mrs Beeton on their walls at all says something about changing attitudes to the recent past. During the twenty-five years following the old Queen’s death, the Victorians had seemed like the sort of people to keep your distance from. Indeed, White’s article in The Times had begun: ‘Mrs Beeton lived in the Victorian era, which, as everyone under 30 knows, was dismally frumpish.’ It was lovely to be free of that mutton-chopped certainty, hideous building, starchy protocol, and, of course, endless suet pudding. But as the years went by, what had once seemed oppressively close now became intriguingly quaint and people began to wonder about the names and faces that had formed the background chatter to their childhood. When Hake had written to the assistant editor of The Times asking to be put in contact with the Beeton family, he explained why he thought the time might be right for the National Portrait Gallery to acquire a portrait of Mrs Beeton: ‘Recently we were bequeathed a portrait of Bradshaw, the originator of the Railway Guide, and I think that Mrs Beeton is at least a parallel case.’

Читать дальше