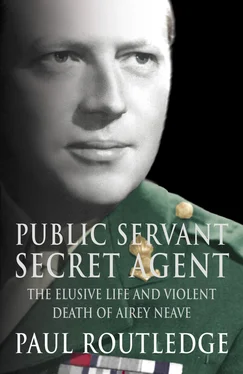

After the Stuka and artillery bombardment of the morning of 26 May, it was only a matter of time before the Germans took Calais. Guderian arrived in person to direct the attack, and street by street British forces were pushed back into an enclave around the port. The Citadel fell at 4.30 in the afternoon, and the commanding officer, Brigadier Nicholson, was taken prisoner. He did not surrender his forces, however. In fact, the garrison never surrendered. Split into small groups, the men were hunted down piecemeal and killed or captured when their ammunition ran out. The Gare Maritime was evacuated, soldiers taking refuge in the dunes. Some remained on top of Bastion 1, above Neave, firing on the Germans, but their position was untenable and they surrendered. Lying in one of the underground rooms, Neave could hear the hoarse shouts of German under-officers and the noise of rifles being flung to the floor of the tunnel. Through the doorway came the enemy, field-grey figures waving revolvers. A huge man in German uniform wearing a Red Cross armband put him gently on a stretcher. He was a prisoner of war. It was a sad ending to a desperately fought battle.

Outside the bastion, British troops were ordered to scatter and try to escape in small parties, an instruction interpreted as ‘every man for himself’. Just before 8.00 that evening, Eden messaged his officer commanding: ‘Am filled with admiration for your magnificent fight which is worthy of the highest tradition of the British army.’ The message never arrived. By then Nicholson was a prisoner and the gallant stand of his men was over. Less than three hours later, troops of the BEF began disembarking at Dover from the beaches of Dunkirk.

The wisdom of the decision to hold Calais to the last man has been hotly debated for sixty years. Neave, who endured the entire bloody nightmare (and whose courage earned him a Military Cross), was naturally partisan, and devoted his most polemical book to the issue. The stand at Calais against impossible odds can be compared with other actions in the history of war, he argues. ‘All through the episode there runs a thread of poor intelligence and indecision.’ Reinforcements were landed too late to do little more than block the town entrances. Tanks were deployed, but not in numbers to hold back the Blitzkrieg. Neave blames those who failed to supply the War Office with up-to-date information on Guderian’s dash for the coast, during which he was pursued and bombed by the RAF. ‘Coordination of intelligence with the RAF had evidently a long way to go,’ he remarked tersely.

Neave also complained of an air of defeatism in the War Office, whose top echelons had evidently decided that most of the BEF had already been lost and troops were needed much more urgently for the Home Front than in the defence of Calais. The fault for the loss of Nicholson’s brigade, he insisted, lay with ‘higher authority’, the General Staff which was obsessed with getting the BEF back to Britain and had no plan for Calais. ‘Indeed, it was not clear who was in charge of the operation.’ In addition, few commanders ‘since the days of Balaclava’ had issued such suicidal orders as Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Brownrigg, Adjutant-General of the BEF, who had ordered tanks to attack Boulogne when it had already been lost. Given Neave’s ancestry perhaps the reference to Balaclava was not the most appropriate.

Churchill was in no doubt that the last stand at Calais was vital for the success of Operation Dynamo which allowed the British army to fight another day. In the British press the defenders were lionised as heroes. Writing in The Times , Eric Linklater argued that the death struggle waged over four days halted panzer troops who would otherwise have cut off the retreating BEF: ‘The scythe-like sweep of the German divisions stopped with a jerk at Calais,’ he wrote. ‘The tip of the scythe had met a stone.’ Guderian himself and the respected historian Sir Basil Liddell Hart disagree with this poetic verdict. In his war diaries, the German general insisted that the heroic defence of Calais, while worthy of the highest praise, had ‘no influence’ on the development of events at Dunkirk and did not delay his advance. Neave is withering on this point. ‘One thing is indisputable, the Tenth Panzer Division was delayed at Calais for four days and not by Hitler,’ he wrote. 7 Guderian, he claimed, was covering up for his failure to take the port earlier, as he had planned.

Liddell Hart argued, somewhat patronisingly, that Churchill was obliged to justify his decision to sacrifice the Calais garrison, but questioned whether it had the outcome asserted by the wartime premier. The panzer division that attacked the port was only one of seven in the area and had been deployed ‘because it had nothing else to do’. The gallant stand was nothing more than ‘a useless sacrifice’, Liddell Hart maintained. Neave was plainly infuriated by this view. He contended: ‘There was nothing useless about the stand at Calais. It hampered Guderian during crucial hours, especially on 23 and 24 May, when there was little to prevent his taking Dunkirk. It formed part of the series of events, some foolish, some glorious, which saved the BEF.’ 8 Glover suggests that the truth lies somewhere in between these two extremes, though strangely he finds it ‘irrelevant’. Nicholson’s brigade had to be sacrificed as a gesture to shore up the crumbling Anglo-French Alliance, even though it was already doomed. ‘At least it made an epic for Britain at a time when all was defeat and withdrawal,’ he writes condescendingly. 9

At the time, however, the military merits of the battle for Calais were far from Neave’s mind. He was about to experience at first hand what he and his men had most feared: Nazi incarceration. He nearly did not make it. On the morning of 27 May, after surviving another night in the bastion tunnel, he was taken by ambulance into the centre of Calais. En route, the vehicle was rocked by a burst of shellfire that forced the crew to take cover. Ironically, this was offshore ‘friendly fire’, from the cruisers Arethusa and Galatea , bombarding the investing German forces. The ambulance restarted and he was dumped on a slab in the covered market of Calais-St Pierre as if he was a piece of meat. In this makeshift field hospital, his imprisonment began.

Neave hated being taken prisoner, at the age of twenty-four, at the very start of the war. It was not just fear of the unknown. German front-line troops, soldiers like himself, had behaved well towards the wounded but it was the Nazis he dreaded. Furthermore, there was a psychological dimension to his capture. A prisoner of war, he discovered, suffers a double tragedy. Most obviously, he loses his freedom. Then, since he has not committed a crime, his spirit is scarred with a sense of injustice. Neave articulated this resentment as a bitterness of soul that clouded the life even of strong men. ‘The prisoner is to himself an object of pity,’ he argued. ‘He feels he is forgotten by those who flung him, so he thinks, into an unequal contest. He broods over the causes of his capture …’ 1

Despite his wound, Neave determined not to fall into this psychological trap. Well-versed in the escape stories of the First World War, he quickly set himself to thinking how to avoid being sent to a prison camp deep in the heart of Occupied Europe, where escape would be much more difficult. Though hospitalised, he was still only thirty miles from England, and much of France was still free of Nazis. Flight was not impossible: Gunner Instone, of Neave’s Second Searchlight Battery, was already busy escaping through France and Spain after knocking out two sentries.

His wounds were too serious, however, to attempt an escape from the hospital to which he was moved, unless he had help. Out of the blue, a French soldier, Pierre d’Harcourt, who had evaded capture from his tank regiment by posing as a medical orderly, offered a solution. Neave could abscond from the ward he shared with four other officers by posing as a corpse. Allied prisoners were still dying, and d’Harcourt, a Red Cross volunteer, could smuggle him out of the hospital in an ambulance in place of a deceased officer. It would not be easy. German guards checked the bodies before they were removed for burial in the Citadel, where Nicholson’s men had fought so bravely. Nor do the plotters seem to have given much thought to disposing of the spare corpse. They hatched extravagant plans to steal a boat and flee across the Channel, but before their ideas could be translated into action d’Harcourt heard that the prisoners were to be evacuated further inland to Lille in late July. The plot had to be abandoned. Nonetheless, Neave found the experience of escape planning very good for morale. It occupied his fertile brain and gave him hope. The elusive d’Harcourt vanished to Paris, where he was active in the first escape lines for Allied prisoners through Unoccupied France before being captured. He spent four years in the notorious Fresnes prison and Buchenwald concentration camp before being liberated, half-dead, in 1945.

Читать дальше