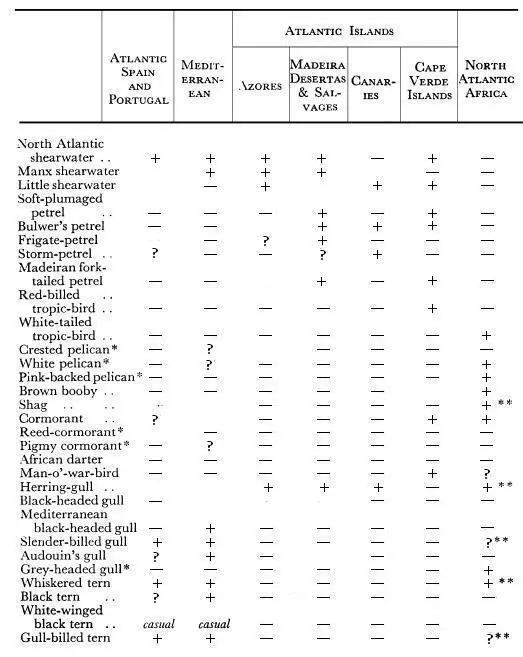

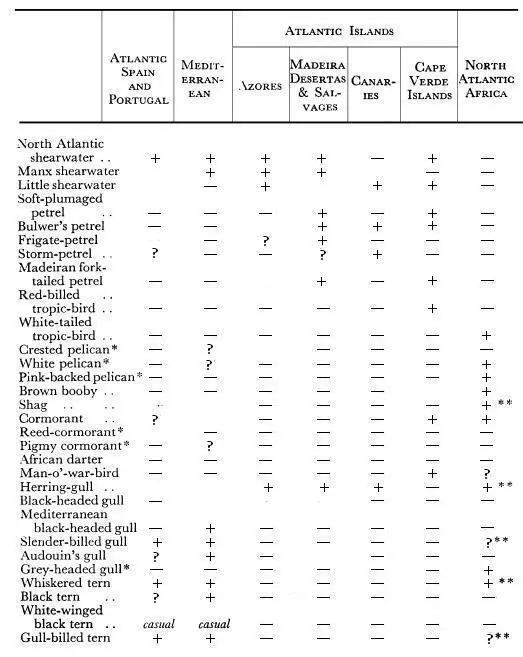

1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...22 Of the species in the table, the crested pelican Pelecanus roseus , the pigmy cormorant Haliëtor pygmeus , the Mediterranean black-headed gull Larus melanocephalus , and the lesser crested tern Thalasseus bengalensis breed on no North Atlantic shore, and the rare slender-billed and Audouin’s gulls, Larus genëi and L. audouinii , are primarily Mediterranean species. It will be noted that three tubenoses have established themselves in the Mediterranean, but that no less than eight species breed in the Atlantic Islands, which have a greater variety of species of this order than any other part of the North Atlantic.

The distribution of breeding sea-birds on these coasts is best illustrated in tabular form :

Of the four main groups of these Atlantic islands, Madeira and the Cape Verdes have probably the largest sea-bird communities, with ten or a dozen species each. One tubenose, the North Atlantic great shearwater, Puffinus diomedea , nests on all of them as well as on the Berlengas of Portugal. Bulwer’s petrel, Bulweria bulwerii , and the little dusky shearwater, Puffinus assimilis , also nest on all four island groups. The Madeiran fork-tailed petrel, Oceanodroma castro , nests on all but the Canaries. The Manx shearwater nests on the Azores and Madeira, but not yet farther south. The little storm-petrel reaches south to the Canaries (although in small numbers and probably to these Atlantic islands only). The rather rare soft-plumaged petrel, Pterodroma mollis , is believed to nest on Madeira; it does so on the Cape Verdes. The beautiful frigate-petrel, Pelagodroma marina , breeds on the Salvages (which belong to Madeira but are nearer the Canaries), the Canaries and the Cape Verdes.

The red-billed tropic-bird, Phaëthon aethereus , the brown booby and the frigate-bird (man-o’-war bird) do not appear farther north than the Cape Verdes. Here the cormorant, which had dropped out in Morocco, reappears as a new race, primarily South African. The bird communities of these islands are only moderately well-known. Most of the sea-birds nest on rocks whose comparative inaccessibility has been both a temptation and a deterrent to the visiting ornithologist. As for the coast of West Africa and the islands lying close to it, no organised investigation of the sea-bird communities of this difficult region has yet been made. We know that one group of species breeds on the Atlantic African coast to Morocco, but no farther south—the shag, herring-gull, the whiskered tern, probably the gull-billed tern, possibly the slender-billed gull. Farther south both white and pink-backed pelicans, Pelecanus onocrotalus and P. rufescens , and the grey-headed gull, Larus cirrhocephalus , reach the tropical sea-coast in some places, and the brown booby nests on at least one island off the coast of French Guinea. The Caspian tern, whose world distribution is, to say the least, peculiar, may have breeding stations on this coast, and the little tern, which we had left behind in Morocco, reappears as a separate race on the coast and rivers of the Gulf of Guinea.

The African darter, Anhinga rufa , reed-cormorant, Haliëtor africanus , and the African skimmer, Rynchops flavirostris , haunt the rivers and in places reach the coast; but they are not sea-birds: and on islands in the Gulf of Guinea the noddy and the white-tailed tropic-bird, Phaëthon lepturus , breed. It is suspected that the frigate-bird may nest on this coast, but its breeding-place has not been found. Neither has that of the bridled tern, Sterna anaetheta , or the sooty tern, S. fuscata , although both species are seen in considerable numbers. There is at least one other riddle: a population of the royal tern, Thalasseus maximus , haunts almost the whole coast of West Africa from Morocco to some hundreds of miles south of the Equator. Systematists have separated it from the West Atlantic population as a subspecies ( albidorsalis ), on valid differences, and it does not appear to leave this coast, yet no ornithologist has yet seen its nest or even its eggs.

Only in the tropical parts of the Atlantic are there still these distributional queries. In the temperate and arctic zones the breeding places of the birds are well-known and described. And with this little mystery we conclude our tour of the Atlantic, for we are back on the equator and can strike west to the St. Paul Rocks, where we began.

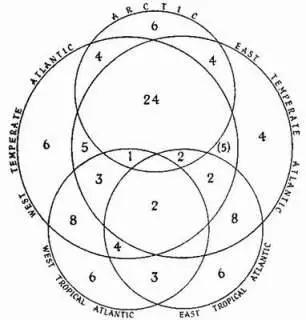

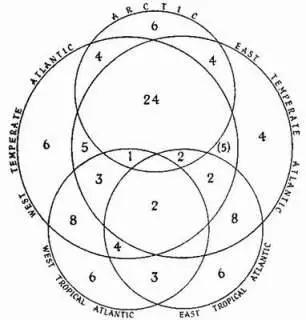

FIG. 2 a The breeding sea-birds of the North Atlantic, arranged by five geographical regions. No species breeds in more than four. Number of species; see opposite page for actual species

The sea-birds of the North Atlantic can be listed in the form of a table (Appendix, see here), and plotted according to which parts of the ocean they breed in, in the form of a diagram ( Fig. 2). For the purpose of completeness, the secondary sea-birds have been included, those belonging to families whose fundamental evolution has probably been non-marine (like anatids and waders) or which are only sea-birds in winter (divers and grebes). Only the more important of these are on the diagram, and they are not otherwise treated in this book. It is interesting that more than half of them are northern ducks which winter at sea, though usually within sight of shore.

It must also be pointed out that several species belonging to the families of primary sea-birds have secondarily taken to life inland, on rivers, or on estuaries, and may reach the sea only incidentally or not at all. Certain West African species, in particular, are river-birds (the pelicans Pelecanus onocrotalus and P. rufescens , the reed-cormorant Haliëtor africanus , the darter Anhinga rufa , the skimmer Rynchops flavirostris ). The terns of the genus Chlidonias are primarily lake and marsh species throughout their range. In North America the gulls Larus pipixcan and L. philadelphia are purely inland species in the breeding season, and the tern Sterna forsteri and the pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos almost so. In South America the terns Phaëtusa simplex and Sterna superciliaris are purely river-species.

FIG. 2 b Actual species. Arrows point to replacement species or to nearest ecological counterparts

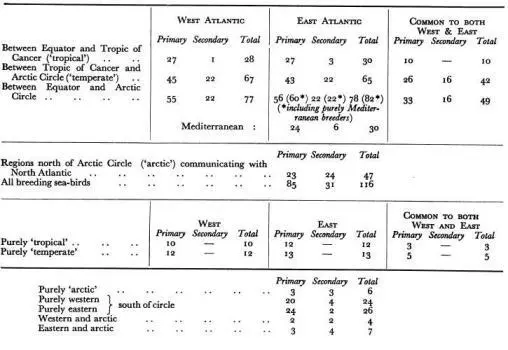

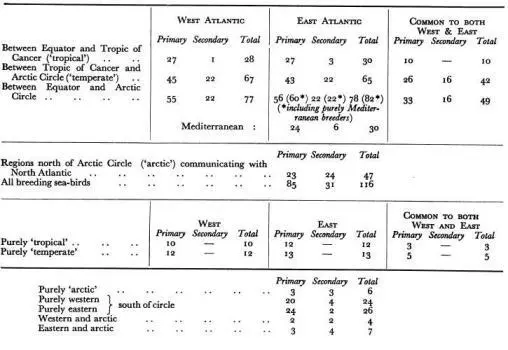

One hundred and eleven species of primary and thirty-two of secondary sea-birds have been identified by competent observers at sea or on some shore in the North Atlantic since 1800: a total of one hundred and forty-one. Of these one primary sea-bird, Alca impennis the great auk, and one secondary sea-bird, Camptorhynchus labradorius the Labrador duck, are now extinct. Of the survivors, eighty-two primary and thirty secondary sea-birds actually nest, or have nested, on or near a North Atlantic or Mediterranean shore or a shore of that part of the Arctic (north of the Circle) that communicates directly with the North Atlantic (this brings in six arctic species: ivory-gull, Ross’s gull, little auk, white-billed northern diver, brent-goose and Steller’s eider). Two further species ( Larus pipixcan and L. philadelphia , see table) are purely inland breeders.

Most remarkably, the number breeding on the Old World and New World sides is almost exactly the same. We can derive the following summary of breeding-species from the Appendix; the totals include the two North American purely inland species, and the two extinct species. Doubtful (“?” in the Appendix) and casual cases are deliberately included—most of them are from tropical West Africa north of the equator where the breeding of the species in question seems likely but, owing to the scanty exploration of the coast, is not formally proved.

Читать дальше