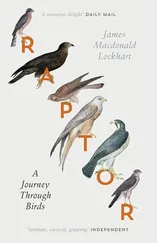

This leaves the three High Arctic sea-birds of the West Atlantic for consideration—the little auk Plautus alle , Sabine’s gull Xema sabini , and the ivory-gull Pagophila eburnea. All three breed in the more northerly parts of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Greenland, though the first may not have more than one colony west of Baffin’s Bay. Sabine’s gull is a rare bird that often nests in arctic tern colonies. The ivory-gull is the most northerly bird in the world in the sense that it breeds nowhere south of the Arctic Circle, but as far north as the land goes. The extraordinary, rare, Ross’s or rosy gull Rhodostethia rosea , which normally nests in the aldergroves of some north-flowing rivers of eastern Siberia, has once bred in Greenland.

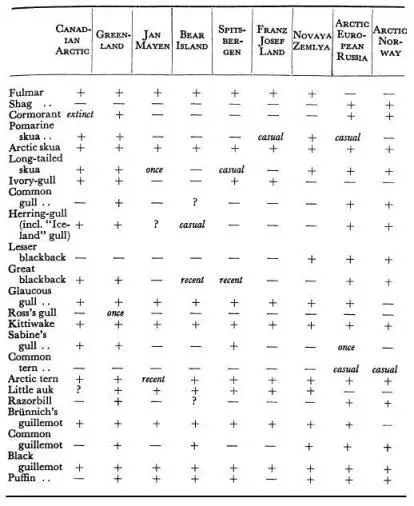

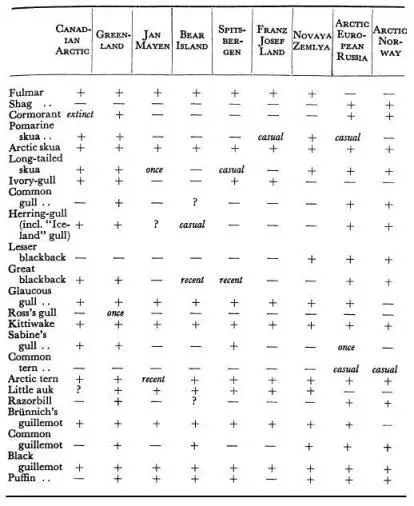

The breeding sea-birds of the lands and islands north of the Arctic Circle belonging to the Atlantic or the Atlantic section of the Arctic Ocean.

With the exception of a few gulls, sea-birds entirely desert the arctic regions bordering Baffin’s Bay and Davis Strait in October and do not return until April. From no other part of the northern hemisphere is there so great a withdrawal of sea-birds to avoid a period of inhospitable climate.

The eastern arctic islands—Jan Mayen, Bear Island and Spitsbergen, Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya, which lie across the Polar Basin where it abuts on the North Atlantic, have a very similar breeding sea-bird community to that of Greenland, though none has so many members. We can best make this comparison in the form of a table, adding columns for the Canadian Arctic, Arctic Russia-in-Europe and Arctic Norway. ( see here)

We now come to the seabird community of Iceland, Faeroe, the British Isles, Scandinavia, the Baltic, and the North Sea and English Channel. This community is very homogeneous, considering the range of latitude over which it is spread, though there are some members which do not reach the south end of this range and a few which do not reach the north. Among the species which are found over almost the entire twenty degrees of latitude are the Manx shearwater, the storm-petrel Hydrobates pelagicus , the gannet, the shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis , the cormorant, the herring-gull, the lesser blackback Larus fuscus , the great blackback, the black-headed gull L. ridibundus , the kittiwake, the common and arctic terns, the razorbill, the guillemot, and the puffin. Species which occupy the more northerly parts of this temperate European stretch include the great skua Catharacta skua , and Leach’s petrel (Iceland, the Faeroes and Britain only), the fulmar, the arctic skua, and the black guillemot. The glaucous gull, little auk and Brünnich’s guillemot breed (in this part of the Atlantic) only in Iceland.

There is a central group of sea-birds which breeds neither as far north as Iceland nor as far south as Atlantic France; this is headed by the common gull Larus canus , and includes also the little gull L. minutus; its other members are terns, the whiskered tern Chlidonias hybrida (only casual, in Holland), the black tern C. nigra , the white-winged black tern C. leucoptera (casual only), the gull-billed tern and the Caspian tern. The populations of all these terns are low, and only two of them (black and gull-billed) have recently bred in Britain, and that casually; their headquarters lie between Holland and the South Baltic. The Baltic Sea, though it has as many breeding terns and gulls as any other part of this stretch of the east Atlantic, lacks tubenoses and has no gannets, shags, kittiwakes or puffins. The long-tailed skua has a somewhat specialised breeding distribution in Lapland, mostly inland. The remaining birds of this temperate stretch of the east Atlantic breed from Britain, the North Sea or the Baltic south beyond its limits; they are the roseate, little and Sandwich terns. Britain is the European headquarters of the roseate tern.

About half the members of this east and north Atlantic temperate sea-bird community are truly oceanic; that is, they may be found in mid-ocean, up to the greatest possible distance from land, wherever there are suitable feeding waters. Storm-petrels, Leach’s petrels and fulmars are the oceanic tubenoses of this community, and we now find that the Manx shearwater also has a right to be considered oceanic. Among the auks the dovekie and Brünnich’s guillemot from the north join the puffins, razorbills and guillemots in ocean wanderings. Here, too, are found all the four skuas of the northern hemisphere and one, but only one, gull—the highly specialised kittiwake. In the waters a hundred fathoms deep or less, that is, on the so-called continental shelf, we find all the birds previously mentioned, together with the gannet, the black guillemot, and gulls of the genus Larus —the great blackback, the lesser blackback and the herring-gull. Once we are within sight of shore quite a number of species are added to our list, and the tubenoses, except for the Manx shearwater and fulmar, drop out. Here are the terns, the black-headed and common gulls, and also the cormorant and shag, the one haunting mostly seas in sight of sandy shores, and other seas in sight of rocks.

By far the most impressive of the sea-bird haunts are the breeding cliffs, where the different species are zoned vertically as well as horizontally. Whether the rocks be volcanic or intrusive or extrusive or sedimentary, we are sure to find Larus gulls breeding on the more level ground a little way back from the tops of the cliffs—fulmars on the steeply sloping turf and among the broken rocks at the cliff edge, puffins with their burrows honeycombing the soil wherever this is exposed at the edge of a cliff or a cliff buttress, Manx shearwaters or Leach’s petrels in long burrows, storm-petrels in short burrows and rock-crevices, razorbills in cracks and crannies and on sheltered ledges, guillemots on the more open ledges where they can stand; perhaps gannets on broad flat ledges or on the flattish tops of inaccessible stacks, cormorants with their nests in orderly rows along broad continuous ledges, shags in shadowy pockets and small caves and hollowed-out ledges dotted about the cliff, kittiwakes on tiny steps or finger-holds improved and enlarged by the mud-construction of their nests, tysties or black guillemots in talus and boulders at the foot of the cliff. These wild, steep frontiers between sea and land are exciting and beautiful. They probably house larger numbers of vertebrate animals, apart from fish, in a small space, than any other comparable part of the temperate world.

Not many sea-birds of the east Atlantic do not breed on cliffs; but the skuas nest on moors, and the terns and black-headed gulls nest on sand and shingle. Many of the Larus gulls, and recently the fulmar, are catholic in their taste in nesting sites, and may be found on moors and even sand dunes. Quite a large number of sea-birds can be inland nesters, even including tubenoses. Fulmars now nest up to six miles inland in Britain, and many of the Larus gulls at much greater distances. The black-headed gull, in particular, is often a completely inland species, since some individuals nest in England as far as they can from the sea, e.g. in Northamptonshire, and may never visit it except in casual search for food.

As we go south along the Atlantic seaboard of the Old World we leave behind in the Channel Islands and Brittany the last elements of certain temperate cliff-breeding sea-bird species—the gannet, lesser blackback, great blackback, arctic tern (only a casual breeder so far south), razorbill and puffin. South of the Bay of Biscay we encounter a large sub-tropical and tropical community of about forty species (a few of which belong to sea-bird families but which have become river-birds or inland birds), which is distributed in four main geographical regions—the Lusitanian coast (the Atlantic coast of Spain and Portugal), the Mediterranean, the Atlantic coast of Africa north of the equator, and the Atlantic Islands. These last comprise the Azores, Madeira (to which pertain the Desertas and Salvages), the Canaries and—near the equator—the Cape Verde Islands. Many species breed, of course, in more than one of these regions, though only the herring-gull (rather doubtfully the little tern and cormorant) breeds in them all.

Читать дальше