At the height of the marriage crisis, it was claimed with a breathtaking simplicity that men and women’s attitudes to him demonstrated whether they were ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and nearly fifty years after his death Harriet Beecher Stowe berated the English nation for any softening in its attitude to him. It seemed to the American novelist that the moral sinews of the nation had been radically weakened by his verse and life, and while she was in some ways a case apart, there was too much agreement on all sides of the political spectrum to dismiss hers as the naïve voice of New England puritanism.

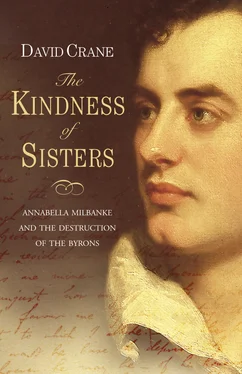

‘England, England!’ 19 she lamented, and if she was wrong in her diagnosis, she was right that the threat Byron offered had not died with him. For the dozen years which followed the triumph of Childe Harold, his poetry and personality had sent his contemporaries scuttling for cover behind the city walls, and yet it was only in death that his rebellion was revealed in its full destructiveness, consuming and maiming lives with all the inexorable power of Greek tragedy until it reached its final, savage climax in the ‘High Noon’ of Byronic Romanticism that forms the core of this book.

This was the first and last confrontation in twenty years between the two women who had been brought together by his marriage and fought over his corpse, the sister he had loved and the wife who had brought about his exile. It took place at the White Hart at Reigate, a small town some twenty miles south of London, on 8 April 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, the year Victorian England gloried in its prosperity and moral superiority with a complacency Byron would have loathed.

Byron, though, had been dead for almost twenty-seven years. Of his great contemporaries, Shelley had been gone for twenty-nine, Keats thirty, Coleridge seventeen, even Wordsworth – the ‘Wordswords’ of Don Juan as he had long since become – one.

And thirteen years into Victoria’s reign, it was a different world. Tennyson, who as a schoolboy had carved Byron’s name into a rock on hearing the news from Missolonghi, had just been presented to the Queen as the new Poet Laureate, his tortured frame tightly trussed in the same court dress that Samuel Rogers had once lent his predecessor. Matthew Arnold – that other representative voice of the mid-century – had just become engaged. Trollope was wondering if he would ever make a novelist. Dickens, never one to be seduced by national prosperity, was beginning Bleak House, Mayhew publishing his London Poor . George Eliot was editing at the Westminster Review, Charlotte Bronte squabbling with Thackeray, her sisters Emily and Anne, already dead. Byron’s half-sister, Augusta Leigh, was sixty seven; his widow, Annabella Byron, fifty-eight.

Byron had been dead for almost as long as he had lived, but for the two women who met at the White Hart his memory had all the sharpness of recent bereavement. For the best part of forty years his presence or legacy had alternately enriched and shattered their lives, and this Reigate meeting was the final testament to his dominance, one last dramatic demonstration of the fear and adulation that had convulsed a generation and for which in their polar antagonisms Annabella Byron and Augusta Leigh stand the perfect surrogates.

It is this that gives both the fascination and significance to this meeting, because the battle that climaxed at Reigate is also in miniature the archetypal struggle of the outsider and the community that had raged around Byron ever since the first publication of Childe Harold . The secret histories of these two women have a misery that no repetition can dim, and yet for all the melodrama of the story this book tells, it is the representative quality that gives a kind of Aeschylian grandeur to the history of incest, bastardy, betrayal, love and hate that in Byron’s name and memory bound them together.

If this focus on the Reigate meeting needs no justifying, the form that has been adopted here requires some explanation. In the first and last parts of this book the methods are those of any conventional biography, but if there is a single episode in the whole Byron saga that demands a freer, more speculative approach, it is this last confrontation between Annabella and Augusta at the White Hart.

With that in mind, the form is that of an ‘imaginary dialogue’, and if this is in part because we do not know what was said, it is not necessity that has determined this option. There can be few lives or deaths that have ever been subjected to the same scrutiny as that of Byron’s, and yet as so often with him the most compelling truths of this narrative lie in regions for which the traditional tools of history or biography are simply not enough.

It is not only that scholarship can never deliver the certainties to which it aspires, but that this meeting has less to do with ‘objective truth’ or ascertainable fact than with the kinds of subjective experience that gradually take on an independent and destructive life of their own. Within the restrictions of orthodox biography it would have been possible to chart the chronological path that took Annabella and Augusta from their first meeting to this last, but what biography could never do is dissolve the barriers between past and present or capture the distorting operations of memory, the co-existence of contradictory but equally valid ‘truths’; could never re-open those avenues that, one by one, are closed by life but remain in the mind; could never, most important of all, do full justice to that sense of waste, that consciousness of other possibilities – other ‘selves’, resolutions, aspirations, untapped or thwarted potentialities of human growth – that was Byron’s terrible gift not just to these two women but to his whole generation.

There is, too, another – entirely fortuitous – advantage to a dialogue of this kind, in that the inevitable whiff of Victorian melodrama about it, the sense of characters speaking out of ‘role’, of addressing not each other but the audience beyond, perfectly captures the way in which they spoke. In a letter written just before the meeting at Reigate, Annabella accused Augusta of never saying or writing anything without a third person in mind, and whether or not that is fair to her it certainly is to Annabella herself whose natural mode of address was the statement or deposition made and obsessively recorded with the judgement of posterity in her sights.

And if this reconstructed dialogue is essentially a fiction, it is a fiction that is strictly circumscribed by historical evidence. The old White Hart in Reigate had passed its Regency peak by the time that Annabella chose it and is now long since gone, and the setting here is essentially a theatrical rather than an historical space, its symbolism and props those of a Pre-Raphaelite painting – this after all is the year Ruskin championed the Brotherhood – rather than a Victorian coaching inn doomed by the advent of the train.

There has, too, been a compression of time to contain within the classical unities the final unfolding of these lives, but those are the only liberties taken. There is nothing here, otherwise, that does not have its source in the thousands of letters, statements, depositions, reminiscences and journals that document the relationship of the two women. Much of it, too, is in their own words, spoken, written or reported over a period of more than thirty years. We have the letters that they exchanged before Reigate, and the minutes taken after. We have the notes, written on a slip of paper in a nervous, almost indecipherable hand, that Byron’s widow took with her to the meeting. We have the correspondence that followed. We know their state of health, how they looked, how they dressed, how they sounded, how they stood and walked, their physical responses to pain. Above all, though, in the mere presence of two elderly women – the one frail from chronic ill-health, the other dying – we have the ultimate proof of that obsession with the memory and influence of Byron that makes their story the story of the age itself.

Читать дальше